The First World War is regarded by many with horror. Ill-considered tactics, stubborn persistence, and a lack of understanding of how war was changing led to massive casualty rates.

In a war renowned for pointless slaughter, some incidents stand out as particularly disastrous.

Austrian Mobilisation

Of all the great powers who marched to war in 1914, Austria was the least prepared. The Austrian government had pushed for war against Serbia despite being woefully unready for the inevitable Russian intervention.

Ignoring the lessons of recent wars, they trained and equipped their armies in distinctly old-fashioned ways. The Austrians were also fielding armies drawn from across a diverse empire. Some regiments contained troops who could talk to each other only in the English they had learned in preparation for their emigration to America.

The Austrian Commander-in-Chief, Conrad von Hötzendorf, was determined to invade Serbia. Persuaded that the real threat was Russia, he sent twelve divisions to join the Serbian offensive; but only for ten weeks. They would then be withdrawn to plug a gap in the line against the Russians.

Unfortunately, he did not inform General Potiorek, the commander on the Serbian front, that the troops were there temporarily. The result was confused and incomplete plans.

Meanwhile, logistics were a nightmare. Trains became bound up in red tape. Troops heading for the front went unfed all day.

At last, Conrad launched an offensive against the Russians. It was a complete disaster. Heavily outnumbered and poorly led, the Austrians lost a third of their strength in three weeks.

From start to finish, Austrian mobilization had been a mess.

Gallipoli

The Gallipoli campaign featured so many failures and errors of judgment it could be considered the most botched operation of the entire war. Begun on February 19, 1915, it was a French and British attempt to engage the Turks in the Dardanelles.

At first, the Allies tried to limit the campaign to a naval action. Their attempts to bombard Turkish shore forts were not just ineffective; they resulted in the loss of four battleships, all of which sunk after hitting mines.

Following the naval fiasco, a ground offensive began on April 25. Most of the troops came from Britain, Australia, and New Zealand, the latter two forming the ANZAC Division. Preparations were rushed, and nobody had tried a beach landing against heavy entrenchments before.

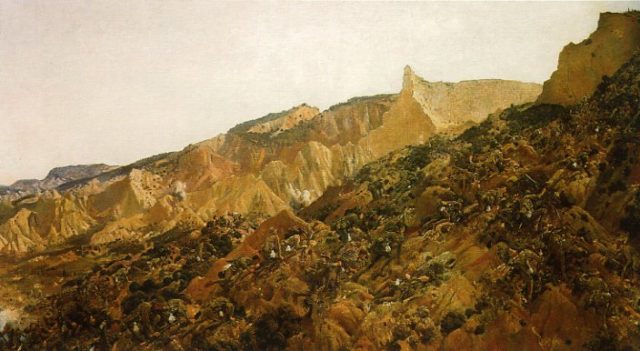

On some beaches, the British suffered horribly in the face of Turkish resistance. Elsewhere they landed safely but had no idea what to do. Meanwhile, the ANZACs became lost and landed amid steep gullies and tangled scrub where they were stalled.

By the end of the day, the Allied forces were confined to narrow beachheads.

Months of fighting left the Allies still trapped on the beaches. In August, they tried fresh landings at Suvla Bay. There they were led by Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Stopford, a 61-year-old with no experience of battlefield command. Rather than advancing quickly, he held his men on the beach while they waited for supplies. The surprise element was lost, and the Turks hemmed them in.

The only real success at Gallipoli came in late December and early January when Lieutenant-General Sir William Birdwood organized one of the most efficient evacuations in military history. The Allies withdrew, having lost 252,000 men.

The Battle of Loos

On September 25, 1915, 75,000 British soldiers began an attack their commanders did not believe in. Told by the government to support French efforts, the ironically named Field Marshal French agreed to attack at Loos.

The attack began with the release of chlorine gas. The light wind carried it out into no man’s land where it sat, not reaching the Germans, just blocking the view. Through it the British infantry advanced, getting lost and failing to reach their targets.

Following this fiasco, two divisions were diverted to continue the attack. After marching for 18 hours, they arrived at Loos at nightfall, hungry and soaked by the rain. The next morning, they too advanced against the Germans.

It was an attack carried out as if the rest of the war had never occurred. As if no-one had witnessed what happened to advancing troops. Marching forward as a massive block, they offered an easy target for the Germans in their trenches. Reaching barbed wire 4 feet high and 19 feet thick, they were forced to halt, unable to advance but still exposed to the Germans.

Of 10,000 men in that second wave, over 8,000 were killed or injured, with not a single German fatality.

The First Day of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme, the leading British offensive on the Western Front in 1916, got off to a terrible start.

It was an operation that suffered from ill omens from the planning stage. General Haig, the British Commander-in-Chief, believed victory would come from punching a hole in the German defenses and sending the cavalry through. General Rawlinson, the Commander on the ground, instead believed in “bite and hold,” advancing and consolidating in small steps. The resulting plan was a compromise that suited neither tactic well.

On July 1, the attack began. Days of preparatory bombardment had churned the ground to muck and warned the Germans of what was coming.

Infantry followed a creeping artillery barrage across no man’s land. However, the creeping barrage was still a technique in development. Advancing 100 yards at a time, it left the Germans free of fire long enough for them to return to their trenches. Bogged down in mud and barbed wire, the British troops suffered withering fire from the Germans.

They made minimal ground at the cost of 57,470 casualties – 19,240 dead, 2,152 missing, and the rest wounded.

Sources:

David Chandler and Ian Beckett (Eds) (1994), The Oxford History of the British Army.

Martin Marix Evans (2002), Over the Top: Great Battles of the First World War.

Richard Holmes, ed. (2001), The Oxford Companion to Military History.

Geoffrey Regan (1991), The Guinness Book of Military Blunders.