The Sopwith Aviation Company was one of the most important manufacturers of fighter planes in the First World War. The company created some of Britain’s most successful planes, which were also used by other Allied nations.

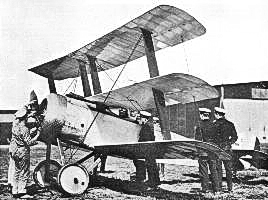

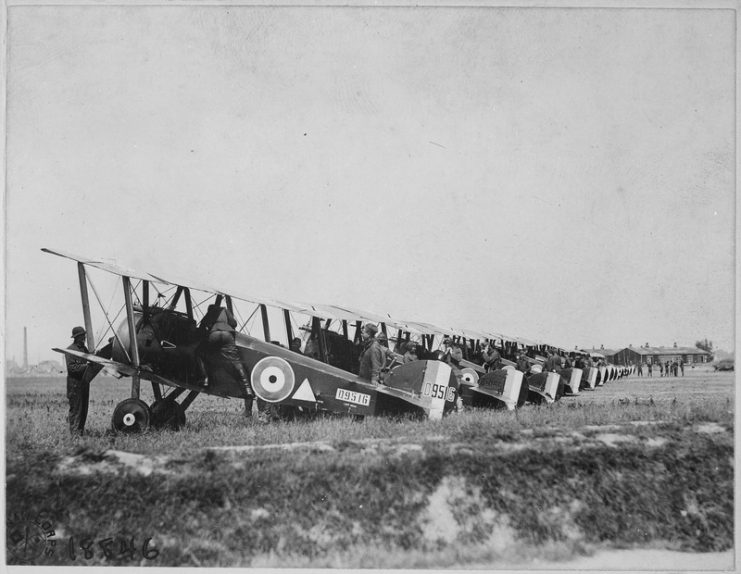

Pup

At the start of 1916, the Germans were dominating the air above the Western Front. Their Fokker Eindecker fighters could outperform anything the Allies threw at them, especially in the hands of such skilled pilots as Max Immelmann and Oswald Boelcke.

This was the period known as the Fokker Scourge.

In response, the Allies frantically worked to create better planes. Sopwith’s contribution, originally named the Admiralty Type 9901, was a biplane with wings 20% shorter than the company’s previous Sopwith 1½-Strutter.

First flown in February 1916, it had a top speed of 112 miles per hour (180 kilometers per hour) and was equipped with a forward-firing Vickers 7.7mm machine gun. Its shortened wings earned it the nickname of “Pup,” which was soon adopted as its official title.

By the time the Pup entered service in the fall of 1916, the Fokker Scourge was at an end. From then until the end of the war, the balance of air power would swing back and forth as each side brought in newer, better planes.

The Pup was one of those. Responsive and maneuverable, it was an excellent dogfighter, deployed by the British both on land and at sea. In August 1917, a Pup became the first aircraft to land on a ship while it was underway.

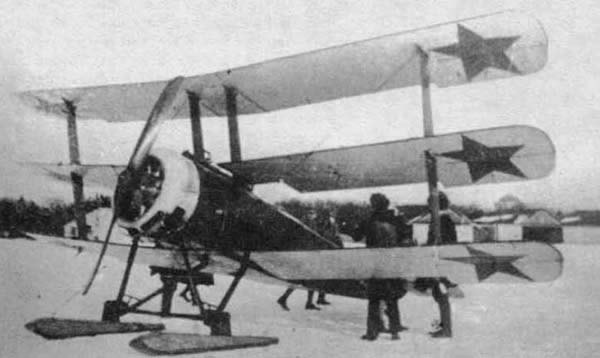

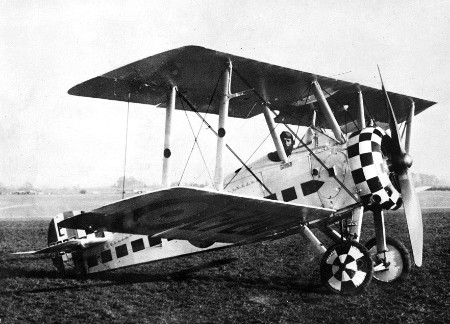

Triplane

Having seen how well the Pup flew, Sopwith’s designers set about building something even better – the Sopwith Triplane, nicknamed “the Tripehound.”

The Triplane was similar to the Pup, but with a more powerful engine and an extra pair of wings. These were designed to give it great maneuverability and a high rate of climb. The Triplane could outclimb any aircraft on either side, though it could not outmaneuver the Pup.

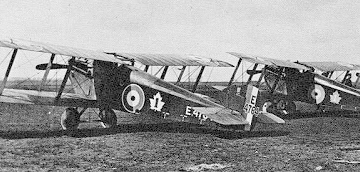

The Triplane was another success for Sopwith. Following its first trial flight against German planes, it was enthusiastically adopted by the Royal Naval Air Service, who used it to great effect in the first half of 1917.

B Flight of No.10 Squadron RNAS, an all-Canadian unit known as Black Flight, scored an impressive 87 kills in 12 weeks using Triplanes.

The Triplane was so successful that Anthony Fokker, the engineer behind the Scourge, immediately set about designing his own three-wing fighter. Yet the Tripehound was never built in large numbers – only 140 were ever made.

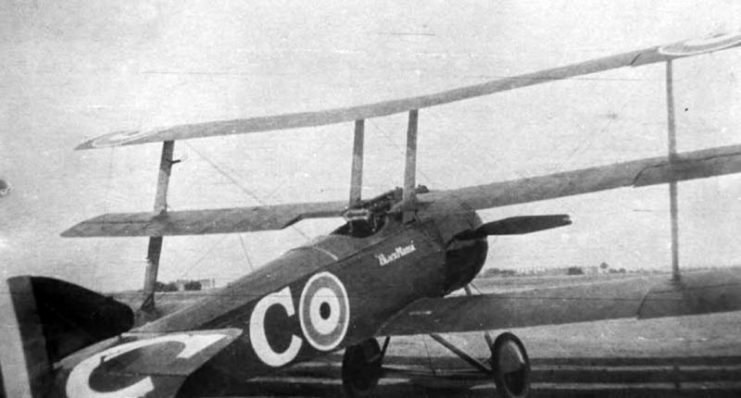

Camel

One of the most famous planes of the war, the Sopwith Camel was a descendant from and replacement for the Pup. First sent into action in the summer of 1917, it would prove to be the most effective plane in the sky.

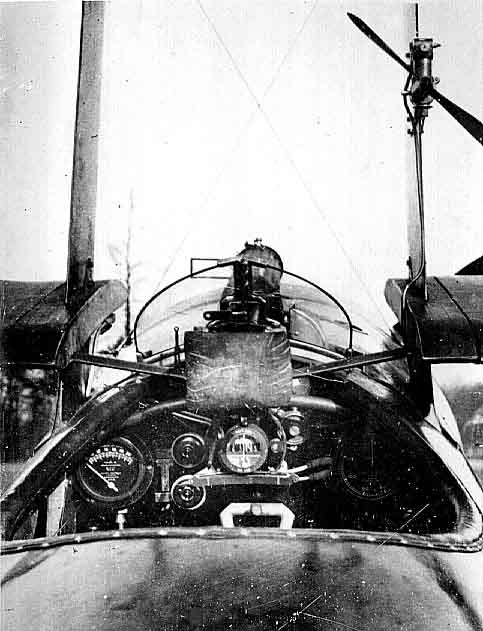

Powered by a Clerget 130hp 9-cylinder air-cooled engine, the Camel had an excellent rate of turn and incredibly sensitive controls. The torque of the engine made it particularly fast at turning to the right – so much so that pilots would sometimes execute a three-quarters right turn instead of a one-quarter left turn.

Camel pilots were regularly able to out-maneuver their opponents, bringing their twin Vickers machine guns to bear.

The Camel’s power and maneuverability came at a price. The sensitive controls and forward center of gravity made it unforgiving to the inexperienced pilot, and it became infamous for weeding them out through crashes.

Right turns dragged the plane down while left turns pulled it up, adding to the complications of the pilot’s job.

Despite these problems, the Camel was popular with pilots in the British air squadrons. Over 1,000 were built and variants were developed for special purposes such as easier stowage on a ship.

The most famous use of a Camel came on the 21st of April 1918, when Roy Brown, a Canadian pilot, used one against Manfred von Richthofen, the man known as the Red Baron and Germany’s greatest air ace.

Who fired the shots that killed Richthofen is disputed, but Brown is one of the leading contenders and undoubtedly played a vital part.

On the 4th of November 1918, Camels took part in the largest dogfight of the war, against 40 Fokker D. VIIs. It was a fitting climax to the plane’s important role in the conflict.

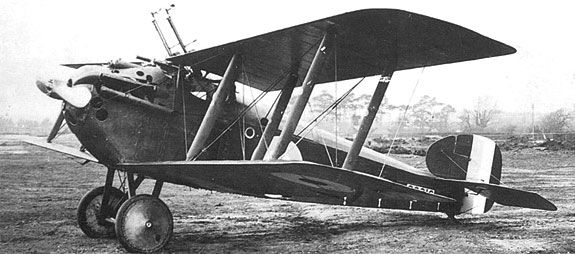

Dolphin

Sopwith’s engineers were constantly learning from their previous planes, finding ways to make something better. And so, only three months after the first flight by a Camel, it was followed into the sky by the Dolphin.

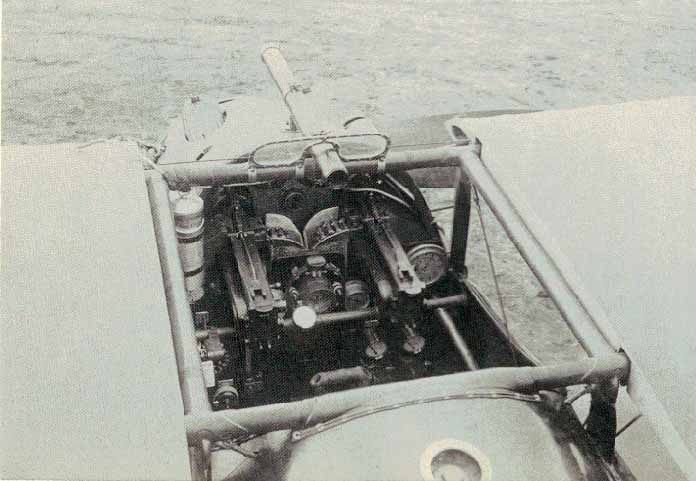

The Dolphin was a slightly unusual looking biplane. The upper wing was mounted close to the fuselage, with the pilot’s head protruding through its center. Designed around improving the pilot’s view and firepower, it carried four machine guns – two firing directly forward, the other two forward and upward.

The Dolphin’s back-staggered wing caused some problems with stalling, but pilots were more concerned with the cockpit. Protruding through the wing, they were left vulnerable if the plane flipped over its nose during landing. A crash pylon was added to the top to protect against this.

The Dolphin entered service in 1917 and proved effective enough for over 1,500 to be produced.

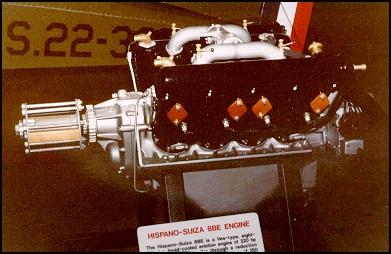

Snipe

Sopwith’s last plane of the war, the Snipe, was an improved version of the Camel. Its 230hp Bentley rotary engine let it fly faster and higher than the plane it was sent to replace. It also featured such innovations as an oxygen supply for the pilot and electric heating in the cabin.

The Snipe arrived at the front only eight weeks before the armistice. While it had little time to make an impact, it proved its worth to the pilots who got to fly it. On the 27th of October 1918, Snipe pilot Major William Barker took part in a spectacular fight against 15 Fokker D. VIIs.

Read another story from us: Submarine Hunters and Flying Boats – Seaplanes in World War One

He destroyed at least four of them before crash-landing, both pilot and plane thoroughly riddled with bullets. Barker was awarded the Victoria Cross.

The Snipe stayed in service until 1927, years after the Sopwith company itself was closed down.