The First World War was a conflict of unprecedented scale and destructiveness. Though its impact was unexpected, the arrival of war itself was not. Though it was decades since Europe’s great powers had fought each other, and a century since they had come together in a single war, many factors contributed to a sense that war was coming and that no-one could stop it.

That sense of inevitability was one reason why war came. But it did not come out of nowhere.

The Alliance System

Webs of international alliances had been a feature of European diplomacy since the Middle Ages. In the 16th century, the web of marriages that solidified those alliances was so incestuous that it increased infertility among the aristocracy. By the 20th century, such marriages were less important, but the alliances were still vital.

These alliances were defensive measures, a way for each country to ensure it had friends on its side. They also ensured that, if war broke out between two of the continent’s major powers, everyone else would soon be drawn in.

The Arms Race

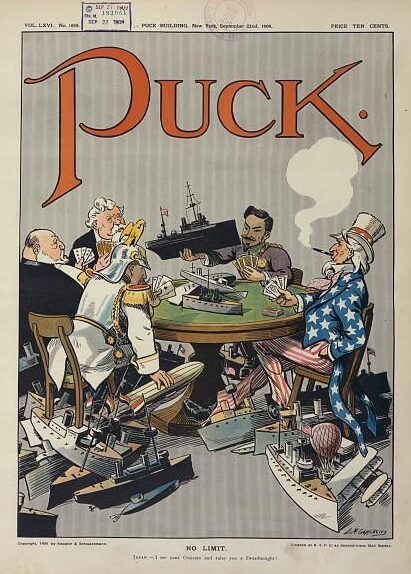

Much like alliances, countries invested in more and more effective weapons for the sake of their security and international influence. This led to conflicts, as nations sought to stay on top.

Germany and Britain, in particular, were in a naval arms race, as the young nation of Germany sought to match the largest navy in the world. For nations with land borders, growing armies caused immediate tensions. Any country would naturally become nervous about an army growing next door, and whether it might have been built to cross their borders.

It is possible that, as David Herrman has argued, the arms race created an impression that time was running out for anyone to win a war against their neighbours’ armies, encouraging nations to act while they had the chance.

Spheres of Influence

An extension of the alliance system, spheres of local influence created crisis points. Some regions were dominated by a single power, but others were disputed through diplomacy and support for local powers.

The flashpoint for the war came in the Balkans, where Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia and the Ottomans were all vying to gain the upper hand through the proxy of governments and opposition groups. But the spark of violence could easily have come in other places.

Imperial Rivalry

The most widespread spheres of influence were colonies outside of Europe though here a different sort of politics applied. The European powers were invested in grabbing territory with no regard for who already lived there.

Colonialism brought prestige as well as political and economic power. This led to some ugly rivalries, the Scramble for Africa, in particular, setting the British, French and Germans against each other. And so, as they looked nervously at each others’ armies, the great powers also greedily eyed their competitors’ colonies and considered which they could most easily seize.

Nationalism and Social Darwinism

Nationalism was a relatively young phenomenon, having come into its own in the 19th century. It contributed to the war in many ways. Two are particularly notable.

Firstly, the prominent nationalism of the great powers encouraged nationalism in other ethnic and cultural groups. Serbian nationalists carried out the attack that launched the war. The ideal of a free and powerful homeland set people with different views of where borders should be at each others’ throats.

Secondly, nationalism became influenced by Social Darwinism – the idea that violent competition between nations was inevitable, leading to advancement through survival of the fittest. Some saw this as the positive side of the war. For others, it made war itself a positive.

French Revanchism

The Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1871 united Germany through the shared joy of victory. For the French it created a very different shared experience, one that would drive French international policy for the next forty years – bitterness and resentment.

Revanchism – a political outlook that revenge on Germany and the recovery of lands lost in the war – became hugely influential in France. By 1914, many saw revenge not just as good but as necessary. Hostility toward Germany was almost a necessity for success in French politics.

German Politics

In Germany too, domestic politics tended toward international war. A rising tide of liberals and left-wingers, especially in the 1912 elections, made the conservative aristocracy nervous. War was a way to remind people of the values of traditional values, whipping up a national spirit.

Primacy of Offensive Warfare

Military thinking in 1914 was radically different from where it would be four years later. Strategists believed that increasingly destructive weapons would give the advantage to offensive tactics. Those put on the defensive were likely to lose.

This meant that the militaries of the great powers all wanted to be the first into action. If war came, they needed to be the attackers, not the defenders. The best way to do that was to start the war themselves, rather than to wait for the enemy to invade.

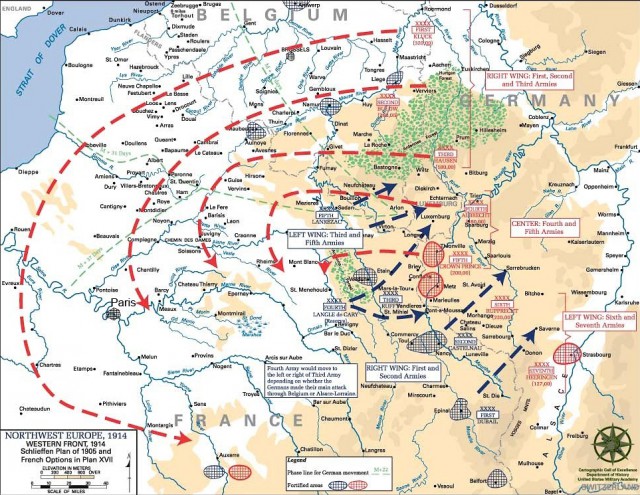

The Schlieffen Plan

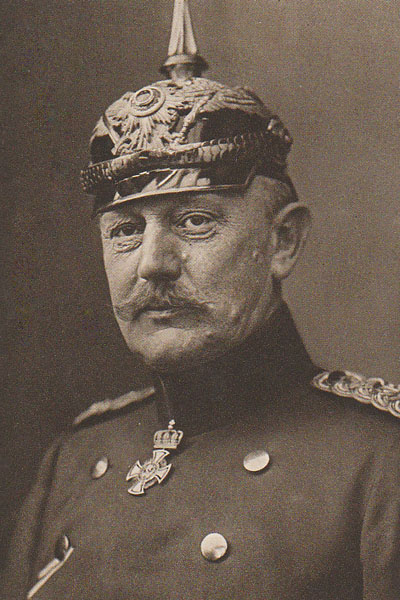

One strategy, in particular, would ensure that the war engulfed the whole continent, and that was the Schlieffen plan. The German General Staff under Count & General Alfred von Schlieffen had developed three plans for going to war – two against France and Russia, one just against France. There was no plan for just fighting the Russians.

When war came with Russia, the Germans, therefore, had two choices – attack France first, following the Schlieffen plan in an attempt to knock out the threat in the west, and guaranteeing French involvement; or abandon the plan, leaving them unprepared to attack France if that country became involved. Believing in the superiority of their planning, and the benefits of offensive strategy, the Germans went to war with France, and the stage was set for terrible destruction.