One of the most destructive events of the First World War, the Battle of the Somme was a 142-day campaign including a series of smaller battles. To the British, it is symbolic of how World War One was fought.

1. Why Fight at the Somme?

By 1916, there was a stalemate on the Western Front. Both sides were heavily dug in, trench positions providing defenders with the advantage despite the expected offensive power of artillery.

The French were eager to remove the German invaders from their soil. While not as powerfully motivated, the British also wanted a win.

To achieve this, the Allies decided to launch an offensive in the Somme region, where British and French lines met. This would allow both armies to take part.

While they were still planning, the Germans launched an attack on the French at Verdun. This drew French resources into a battle of attrition there, placing the onus upon the British to fight the Somme campaign.

The attack now had an extra purpose – to draw away German resources, relieving pressure on Verdun.

2. One Plan, Two Strategies

The plan for the Somme was directed by the British commander-in-chief, General Haig. Haig still believed, as he had from the start of the war, that it could be won by breaking through the enemy defences and exploiting that opening with cavalry. At the Somme, he planned to make this breakthrough at the Pozières ridgeline, while a diversionary attack took place at Gommecourt to the north.

The commander of the Fourth Army, who would make this assault, was General Rawlinson. Based on his experience of the war so far, he believed that the best option was “bite and hold” tactics, making small advances and then consolidating. The eventual plan of attack became a compromise between the two men’s different strategies, ideally suited to neither.

3. Preparing to Attack

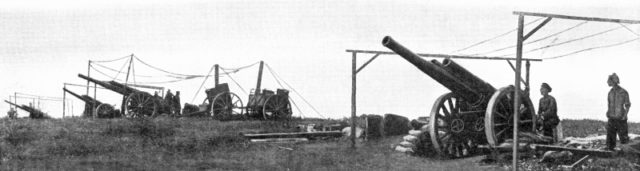

British artillery began a colossal bombardment on 24 June. 1.7 million shells were fired in less than a week while miners dug tunnels beneath 17 key German defensive points and filled them with explosives.

The bombardment was less effective Haig hoped. Around 30% of the shells did not explode, and those that did failed to cut the barbed wire. The Germans retreated safely into their bunkers and weathered the storm of shrapnel.

The main assault was meant to begin on 29 June, but heavy rain turned the ground to impassable mud. And so the attack was delayed.

4. The First Day of the Somme

On 1 July, the attack began. Infantry poured from their trenches, following a creeping artillery barrage towards the German lines. But the creeping barrage had not yet been mastered. Advancing in 100-yard steps, it left the Germans free of fire long enough to return to their trenches and face the attackers. The mud had not dried up, the barbed wire was largely intact, and the British soldiers found themselves bogged down in the face of the enemy.

The British made minimal advances at a huge cost. They suffered 57,470 casualties – 19,240 dead, 2,152 missing, and the rest wounded. Even in the context of the First World War, that day was unprecedented in its horror.

5. The French on the Somme

Though they had not been able to commit as many troops as originally intended, the French took part in the attack. Thanks to their large numbers of heavy guns, French forces were generally more successful than the British on the first day, and their support allowed the British in the south to make the most significant advances.

6. Return to Attrition

In Haig’s view, success in war came from two elements – a campaign of attrition to wear down enemy reserves, and then a strong attack to break through the weakened enemy. His attack having failed, he reverted to attrition.

What followed was 142 days of grinding warfare. The British had some successes, including well-organised attacks on Longueval and Bazentin on the night of 14 July. But progress was slow and costly, and German counterattacks sometimes pushed the Allies back.

7. Bring on the Tanks

The Somme witnessed the first ever use of tanks in warfare. On 15 September, the British launched their new weapons. Shocked German soldiers saw large armoured vehicles rolling towards them across the mud, heavy guns blazing.

The tanks faced some difficulties, as did everyone fighting in that muddy, broken ground. But their presence helped with the capture of High Wood and a breakthrough into the German third line.

The Somme became the testing ground for one of World War One’s greatest innovations.

8. Claiming Victory

The capture of Beaumont Hamel was a British objective for day one of the offensive. Its eventual capture on 18 November, four-and-a-half months later, marked the end of the campaign.

Haig declared the Somme a success. Though the British had lost 415,000 men and the French 200,000, the Germans had lost an estimated 650,000. Enemy resources had successfully been reduced – that the Allies had suffered almost as devastating losses was glossed over.

Territory had been taken from the Germans, whose lines had been pushed back as much as nine kilometres in places. That this was little gain for 142 days of fighting and 615,000 lives, and that it was nowhere near the breakout Haig had envisaged, was also set aside in declaring victory.

The Allies had suffered less than the Germans. For Haig, that was a success.

9. An Iconic Moment

Battalions from every British infantry regiment took part in the Somme campaign. As a result, the whole army and much of British society was touched by the losses. That first day’s offensive, and Haig’s sacrifice of hundreds of thousands of men for almost no advantage, became a powerful symbol of what was worst about the war.

Strategy dictated that fighting at the Somme was the best move for the Allies. But the way they fought was far from ideal, and the consequences truly awful.