York’s battalion was charged with capturing a number of German machine gun positions situated on the other side of a valley.

Rare is the pacifist who changes his mind and becomes a warrior, and rarer still is the pacifist who not only fights but also ends up becoming a war hero. Alvin York was such a man. When drafted into the United States Army in 1917, he stated that he was a conscientious objector and didn’t want to fight.

When he was made to fight regardless of his beliefs, though, he took to the task with gusto, and ended up becoming one of the most decorated American soldiers of the First World War. He was awarded the Medal of Honor after an astonishing act of heroism and valor in which he almost single-handedly killed 25 German troops and captured another 132 of them.

Alvin Cullum York was born in a log cabin in rural Fentress County, Tennessee in 1887, the third eldest of eleven children. The York family was poor and survived by farming, hunting and fishing in the mountains, and as such the children received little in the way of formal education. Alvin York’s childhood spent in the mountains, though, did make him a crack shot with a rifle.

A troubled young man, he attended church but also spent a lot of time getting pass-out drunk in disreputable saloons, where he would often get into brawls. A firebrand sermon at a revival meeting at the end of 1914, though, led to his becoming a born-again Christian.

From that moment on he took his religious beliefs very seriously. It was on these grounds that, when he registered for the draft into the United States Army, he stated that he did not want to fight in the war.

Despite registering as a conscientious objector, he was nonetheless drafted in the army and began his military training in November 1917. He was sent to France with Company G, 328th Infantry, 82nd Division.

He frequently discussed his religious views with his commanding officers, who eventually managed to convince him that he could be a good Christian and still fight in the war and kill the enemy. Once York had taken this message to heart, he approached combat on the front lines with an entirely new view – one that was to earn him a place in history.

The first action York saw was during the St Mihiel offensive in September 1918. The action for which he achieved fame as a war hero, though, occurred during the Meuse-Argonne offensive in October. York’s battalion was charged with capturing a number of German machine gun positions situated on the other side of a valley.

York and his unit – seventeen men in total – attempted to achieve this by sneaking around the back of the German lines. What they did not know was that the Germans saw them coming.

When the American troops got within range, the Germans suddenly unloaded on them with heavy machine gun fire. Nine of the seventeen men were cut down within seconds, including the commanding officer. This left York – then a corporal – as the commanding officer of the unit.

York knew that he had only two options: take out the German machine gun nest, or see the remainder of his unit destroyed. At that moment, with German machine gun bullets flying thick and fast around him, and no cover in sight, the sharpshooting skills he’d learned growing up in the mountains came into play.

Firing off shot after deadly-accurate shot, York counterattacked the German position, taking out an enemy soldier with every single shot he fired. There were thirty German soldiers all trying their best to kill him, but unfazed he engaged them all, exacting a deadly toll with his sharpshooting.

As he fired the last round he had in his M1917 Enfield rifle, six German soldiers charged out of a nearby trench with bayonets fixed, aiming to finish off York without the aid of bullets. Standing his ground, though, the former conscientious objector drew his Colt M1911 .45 pistol and took out all six of them.

A German officer then jumped up and emptied his own pistol at York, but, as if a divine force was protecting him, every single shot missed.

Whether the German officer thought at that moment that God was protecting York, or simply that he was a man who couldn’t be killed, he nonetheless realized that continuing to fight would simply mean more of his own men losing their lives. Speaking English, the German officer surrendered to York, and commanded his troops to lay down their weapons and surrender as well.

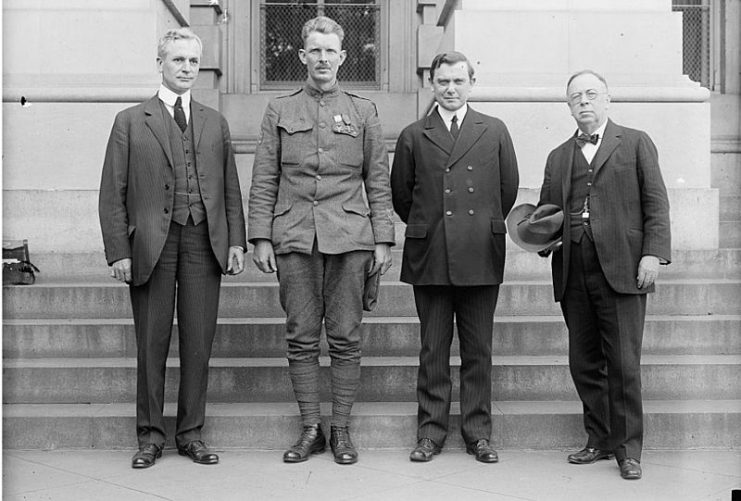

At the end of the day, York and the seven men of his unit returned to the Allied lines with 132 German prisoners in tow, while at the site of York’s stand 25 German soldiers lay dead. For his actions, York was promoted to the rank of sergeant and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, which was later upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

He also received decorations for his valor from a host of other nations, including France and Italy. York credited his astonishing feat that day to a higher power watching over him.

After the war York became something of a celebrity in America, but this was something he never used for his own personal gain. Instead, he used his newfound fame to raise funds for charities. He built a school to educate the poor, rural children of the community in which he had grown up, and petitioned the US government to build a highway through the area to improve the economy.

Throughout the Great Depression he continued to support the school he had built, even mortgaging his own farm to fund a bus to transport kids to and from the school. In contrast to his former pacifism, he also argued for an interventionist approach to the Second World War, urging the United States not to let Hitler’s evils go unchecked.

When the US did eventually enter the Second World War, York tried to reenlist in the infantry even though he was then 54 years old, overweight, and suffering from a number of chronic illnesses.

Although his application to enlist as a combat infantryman was rejected on these grounds, he was allowed to join the Army Signal Corps, in which he was commissioned as a major. He toured the training camps to boost morale, and raised funds for charities.

After the war York sold the rights to his life story to a film production company, and used the profits to build a Bible school. He was also outspoken on the issue of dealing harshly with the Soviet Union. He continued to do good deeds despite poor health in his later years, and eventually passed away at the age of 76 in 1964.

Despite the fact that he was commissioned as a major during WWII, the press continued to refer to him as “Sergeant York” throughout his life – and it is as Sergeant York, one of the most decorated American heroes of the First World War, that history will continue to remember him.