In the spring of 1918, the Germans went on the offensive. With new tactics including Stormtroopers and a “fire-waltz” artillery attack, it was the most daring and successful campaign of the war on the Western Front.

However, as the Allies were driven back, they achieved some victories. One of these took place on July 4, 1918, at Hamel. There, the fighting took on an added significance due to the combination of troops that saw action.

Hamel and the Spring Offensive

From March 1918, the German spring offensive pushed the Allies back in France and Belgium. In one last push to win the war before American reinforcements arrived, the Germans almost managed to drive a wedge between the British and French forces.

One of the reasons for the German success was their implementation of new weapons and tactics. Stormtroopers led the assaults. Elite soldiers equipped with grenades and recently developed light machine guns they smashed their way into Allied trenches. They were powerful because they were combined with the “fire-waltz,” an artillery tactic that incorporated a range of different shells to achieve great devastation.

The Germans had brought new weapons, troops, and tactics to the field. At Hamel, the Allies would do the same.

British, Australians and Americans

Hamel was a village on high ground near Amiens. The Germans had taken it in Operation Gneisenau, the fourth offensive in the 1918 campaign. Holding this position gave the Germans the chance of enfilading fire against any Allied counter-attack in the area. It needed to be retaken before the much-needed counter-attack could start.

The lines around Amiens were held by the British, including troops from Australia, New Zealand, and other colonial territories. The German advance had hit the British hard, forcing them and the French into retreat earlier in the year. More troops were needed, and the Allies looked to the Americans.

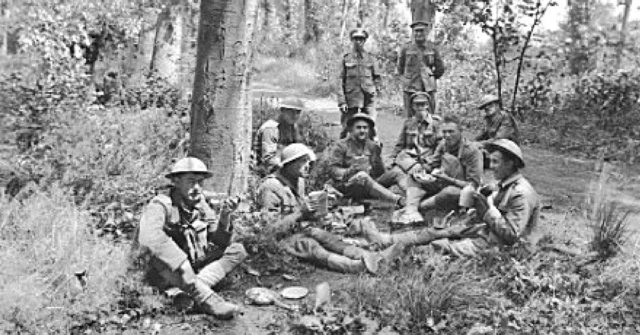

The attack on Hamel was led by the infantry of the 4th Australian Division, with support from other Australian machine gunners and British tanks.

The American 33rd Division had been training with the Australians. The British pushed hard for them to be included in the attack. The American General Pershing was reluctant to allow this but eventually accepted the plans were too far advanced to avoid committing his troops. The soldiers of the 33rd Division were more enthusiastic than their commander. They were eager to see action.

The result was a force that combined the experience of the Australians with the fresh-faced enthusiasm of the Americans. Australian troops had been involved in some of the hardest fighting of the war and had rightly earned a reputation. The Americans were volunteers not yet worn down by the horrors of trench fighting, and eager to prove themselves.

Hamel became the site of a powerfully symbolic moment. For the first time since the American Revolution, British and American troops came together to attack a shared enemy. After many generations, old enemies had become friends.

Combined Weapons

The attack on July 4 was planned and executed with almost perfect precision. By combining different military elements, it ensured the swift fall of the strategically vital village.

First came the artillery barrage. Planned and controlled with high precision, it used the lessons both sides had learned through four years of bombardments. Artillery, a form of weapon centuries old, had come a long way since the start of World War One.

Then came the tanks, the newest weapon of the war. Developed by British engineers and first deployed in 1916, the tank was still a novelty. Tank tactics were in their infancy, and errors were common. After a year of use, tanks had still become bogged down and ineffective when thoughtlessly deployed at Menin Road in 1917. This time they were effectively used and performed as expected, clearing the way for the infantry.

The infantry had the toughest task. As the tanks rolled on, they had to mop up the pockets of stiff German resistance that remained. Corporal Thomas A. Pope earned the Congressional Medal of Honor for his service in the American forces that day. Charging with his bayonet into a German machine-gun nest, he killed half the crew and took the rest captive, holding them on his own until his section could catch up with him.

The Royal Air Force (RAF) were in support, airdropping 100,000 rounds of ammunition to the Australian machine gunners. It was the first such airdrop in history.

Combined Air Arms

The existence of the RAF represented a new role within the British armed forces. On April 1, the separate Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service had been combined, creating the RAF.

At the start of the war, the use of planes had been a novelty. The British military realized where the future lay and air power was more manageable run as a unit.

Sir John Monash

The plan to take Hamel was designed to take 90 minutes. Most operations in the First World War became bogged down, taking many times longer than expected and failing to achieve their goals. This one was a total success that over-ran by a mere three minutes.

The man behind it, Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash, was so meticulous he is said to have resented those extra three minutes. Monash was an Australian Jew fighting in the British army. He was an engineer and militiaman who had risen to command regular troops in a massive war. An innovator in a war notorious for repetitive and uncreative tactics.

Hamel was a place of combinations. Through them, it became a place of great Allied success.

Source:

Martin Marix Evans (2002), Over the Top: Great Battles of the First World War.