Even though Imperial German Navy was a well-prepared force during WWI, with a considerable amount of powerful vessels, it was still no match for the traditional European naval superpower – Great Britain. That is why the Germans hoped to lure a large portion of the British Grand Fleet near the coast of Jutland Peninsula, gaining slight tactical advantage through entrapment.

The Battle of Jutland, which took place on May 31st and lasted for one day, has often been cited as one of the greatest naval battles of WWI.

Evening the Odds

The punching fist of the German fleet consisted of 16 dreadnought-class battleships. Though these were a considerable force at the time, they were still no match to the 28 dreadnoughts that the British had in their possession. This is why the Germans decided on a risky “divide and conquer” tactic; they would conduct raids in the Northern Sea and bombard the English coast, thus aggravating the British Navy, forcing them to commit reckless attacks, without enough strategic planning.

Once the Brits were hooked into pursuing a small German attack force, they would be surrounded by German U-Boats. This is how the German High Seas Fleet intended to even the odds with the British Navy. But in 1916, the man behind this strategy, Admiral von Pohl fell ill and was replaced by Admiral Reinhard Scheer, who believed that the German fleet should be used more offensively.

In addition to this change of doctrine was the prolongation of the Naval Blockade of Germany which lasted throughout the war. The blockade ensured isolation of the German Empire in an effort to restrict the maritime supply of goods to the Central Powers, including Austro-Hungary and Turkey.

Around the same time, Scheer insisted that Germany should enter into an unrestricted submarine warfare, which included the sinking of neutral merchant ships, most notably the American ones. This ultimately provoked the US to join the conflict in 1917.

Preparing for Battle

Between May 13 and May 29 the Germans were preparing the waters around Jutland for battle. They sent in ten submarines on regular patrols to ensure their preparations remain uninterrupted. One of those submarines, the U-72, was ordered to lay naval mines, but due to engine problems had to back down ― a misfortune that denied the Germans the advantage of a sea minefield.

The preparations prolonged because repairs needed to be made on the battlecruiser SMS Seydlitz which suffered severe damage in previous engagements. The submarines were ordered to avoid skirmishes prior to the battle and to remain undetected of possible. Nevertheless, the British Navy noticed an unusual submarine activity in the waters around Jutland. Counter-patrols were launched as a reaction.

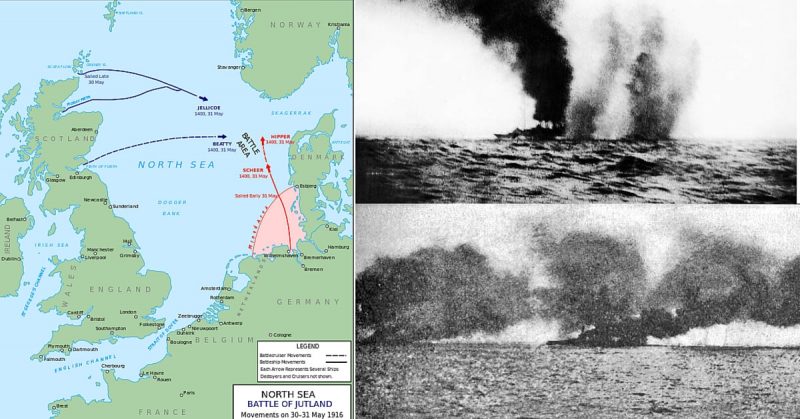

Prior to the Battle of Jutland, a patrol of German battlecruisers under the command of Franz Hipper were sent to Skagerrak, a bay in the North Sea. This is where the German fleet initially assembled.

The British were well informed on the German activity in the region, for they had obtained a code book, initially seized by the Russian Navy in 1914. After intercepting coded messages, they prepared for a response. Admiral Jellicoe with his force of 16 dreadnoughts joined with Vice-Admiral Martyn Jerram and his 8 dreadnought battleships west off the coast of Jutland on May 31st, 1916.

The Battle Commences

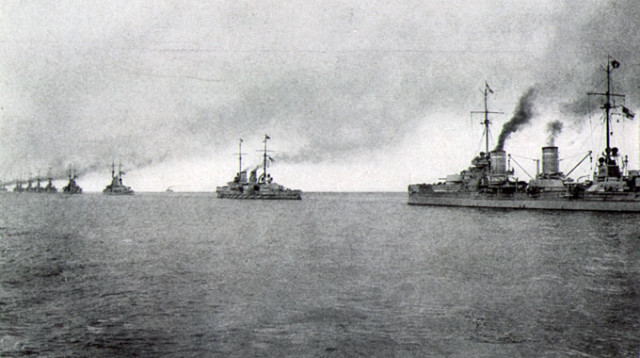

Jellicoe’s fleet was split into two sections. The dreadnought Battle Fleet with which he sailed formed the main force and was composed of 24 battleships and three battlecruisers. Admiral Scheer’s ships were divided into the main battle force of 16 dreadnoughts, 6 cruisers and 31 torpedo boats and a reconnaissance group under Franz Hipper, which consisted of 5 battlecruisers, 5 light cruisers, and 30 torpedo boats.

Initial contact occurred at 14:00 hours on May 31 when the scouting forces of both sides confirmed visual contact. Half an hour later, first shots were fired by British light cruisers that forced the German torpedo boats to withdraw back to their main formation together with the battlecruisers. The British force pursued the boats and due to a communication breakdown went too far ahead of its main formation, risking carnage by Hipper’s battleships.

The battlecruiser detachment of the British fleet, led by Admiral David Beatty was heading into a trap as it approached the main German force under Admiral Scheer. The detachment got locked into a battle and the Germans drew first blood. The flagship with Beatty aboard, HMS Lion was damaged severely but managed to stay functional. HMS Indefatigable, unfortunately, didn’t live up to its name, as it was sunk by the SMS Von der Tann, leaving 1,016 sailors and officers dead. There were only two survivors.

Hipper’s baiting mission was close to completion as he was approaching the main force in his retreat. HMS Queen Mary met with SMS Seydlitz and SMS Derfflinger. The initial phase of the German plan was going well since the Germans gained a slight advantage over the British.

However, the tables turned quickly.

After a fatal skirmish for the British fleet, Beatty turned around and headed a course towards the lagging Jellicoe’s dreadnoughts. The Germans started chasing them.

Hipper’s ships fired on the retreating fleet, scoring several more hits. This boosted their morale and led them to continue the pursuit. It was an extremely foggy day, which was one of the reasons why the communications that relied on visual contact were so useless. Meanwhile, Jellicoe decided to spread his fleet and prepare for battle. Beatty turned on Hipper once again and the cat-and-mouse game continued.

Hipper already had several ships damaged and decided to regroup with Scheer. In the battle that followed, the Germans severely damaged two more British ships, before sinking a third. After that, Hipper’s own flagship was sunk, but the skipper abandoned ship and moved to a torpedo boat that had arrived nearby.

The battle raged all night, with multiple casualties on both sides. Even though the Germans were arguably winning the battle, their numbers were just not enough to take on the British Grand Fleet. The two sides eventually went their separate ways, both with great losses.

![Invincible blowing up after being struck by shells from Lützow and Derfflinger. By unknown. Taken from a destroyer nearby. - Fighting at Jutland:The personal experiences of forty five officers and men of the British Fleet. London Hutchinson and Co, Ltd. 1921. Also available online at internet archive [1], PD-US](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2016/05/1024px-InvincibleBlowingUpJutland1916-640x349.jpg)

This Pyrrhic victory brought the Germans a temporary satisfaction with both Scheer and Hipper being awarded the Pour de Merite medal.