Five hundred years before the start of World War I, the Teutonic Knights were gravely defeated by Slavic and Lithuanian forces at the Battle of Tannenberg (otherwise known as Grunwald). In 1914, the Germans practically slaughtered the entire Russian Second Army over the course of just four days, just miles away from the site of the 1410 battle. Given this, German officials couldn’t help but name the site their historic win, “Tannenberg.”

Early days of World War I

Germany entered the Great War following the Schlieffen Plan, influenced by Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and his vision of a sweeping German invasion of France and Belgium. The plan was to gather the country’s allies, before moving toward France via the Netherlands, where they would defeat the French Third Republic. At the same time, a limited German contingent would travel toward Russia to fend off potential attacks, until the triumphant soldiers arrived to bolster their numbers.

The entire strength of the German Army in 1914 totaled 1,191 battalions, the majority of which were deployed to France while the Eighth Army of East Prussia, comprised of just 10 percent of Germany’s entire military, set their sights on Russia.

Meanwhile, France organized a speedy mobilization of its forces, followed by an immediate attack to drive back the encroaching Germans. Buying time for the British and Russians to establish their defenses, neutral Belgium was defeated after two weeks of intense fighting during the Battle of Liège – the first official battle of WWI.

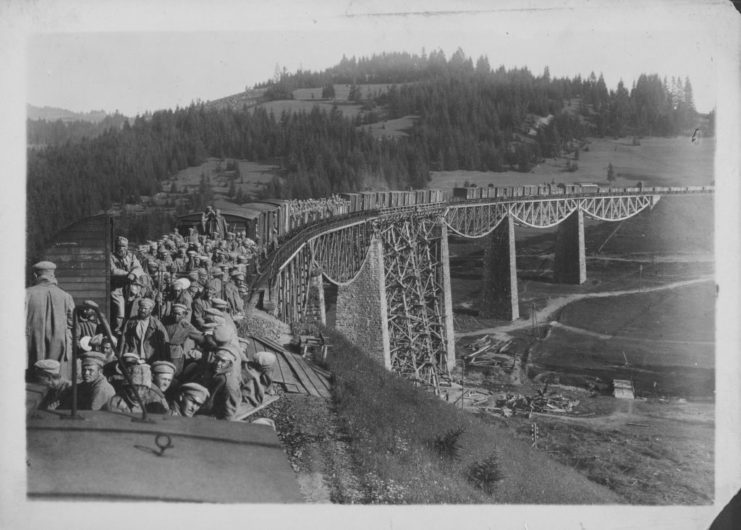

Waiting for the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and their Russian allies to join them, France knew it would take time for Russia to mobilize. The country’s limited railway network – 75 percent of Russian railways were still single-tracked – meant it took 60 days before enough divisions were in action.

Battle of Gumbinnen

The Eighth Army was by far the most inexperienced company in the Imperial German military. It was comprised of reservists and garrison troops, and led by Generaloberst Maximilian von Prittwitz, who was surprised to find the Russians had mobilized much faster than he’d anticipated.

The Eighth soon learned the Russians had beaten them at their own game, sending two armies to attack East Prussia. Germany subsequently ordered von Prittwitz to attack the Russian 1st Army Corps during the Battle of Gumbinnen on August 20, 1914. Both sides sustained heavy losses, and with a second Russian force heading toward them, von Prittwitz wanted to retreat – but German officials knew standing down wasn’t an option.

von Prittwitz was replaced by two legendary military leaders: General der Infanterie Erich Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenberg, a famed field marshal who’d lead the Imperial German Army throughout the remainder of the war along the Eastern Front. Now under new leadership, the Eighth Army went into battle against the unprepared Russians with every advantage they could muster.

Was Russia doomed from the start?

The lead-up to the Battle of Tannenberg likely sealed Russia’s fate before the fighting even began. The Russian Army, with little experience, made a massive mistake when it came to its radio communications. Orders were being transmitted to personnel on open radio frequencies, and even though they were encoded, the Germans easily intercepted the messages and used them to their advantage.

According to the National Security Agency (NSA), the Battle of Tannenberg was the first in human history in which the interception of enemy radio traffic played a decisive role.

One message revealed that the 1st Army Corps wasn’t pursuing the Eighth Army after all – they were, instead, turning north toward Königsberg, Prussia with the 2nd Army following close behind. The two were separated by the 50-mile chain of the Masurian Lake District, slowing their advance toward Königsberg.

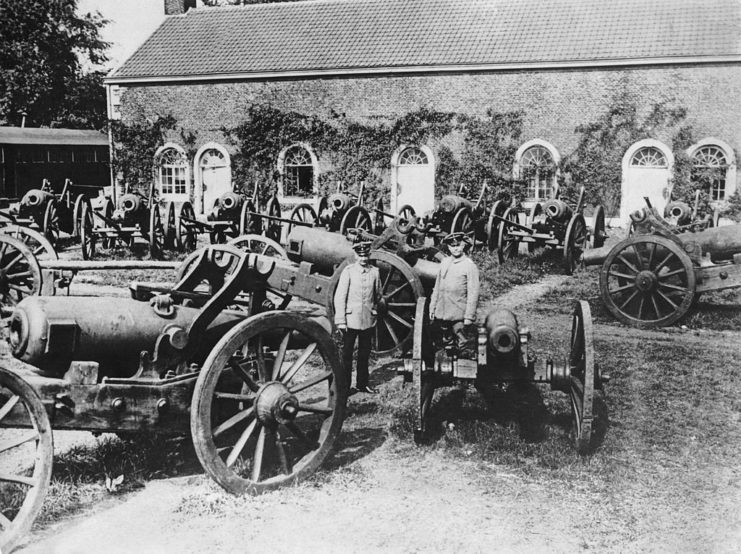

Using the intercepted radio messages, Ludendorff, a military theorist, came up with a strategy to attack the 2nd Army south of the Masurian Lakes. The 2nd’s commander, General of the Cavalry Alexander Samsonov, was already hindered by a slow supply chain, poor communication and the difficulty of navigating a large force with heavy artillery through the are’s impossible terrain. Soon, he and his men found themselves completely surrounded by the Germans.

“Imagine this Russian army as a bulge pressing into Germany and the Germans strike at a point where the bulge begins and cut off the vast majority of the Russian forces in the middle,” explains military historian, Jay Lockenour. “Because of communication problems, the Russian commanders didn’t know that a major attack on their flank was underway until half a day too late.”

Samsonov’s men were spread out over a 60-mile stretch, with the center, right and left wings separated – practically inviting the Germans to attack both wings. Meanwhile, the 1st Army Corps, led by General of the Cavalry Paul von Rennenkampf, was in no rush to come to the 2nd’s aid. Instead, a lapse in communication failed to urge him to pick up the pace and change his focus from Königsberg to the Masurian Lakes.

On August 26, 1914, Ludendorff ordered General der Infanterie Hermann von François and his I Corps to attack and break through the Russians’ left wing.

Who won the Battle of Tannenberg?

The height of the Battle of Tannenberg occurred on August 27, with the German heavy fire focused on the left wing. Soon, Russian troops began to flee across the frontier, toward Neidenburg, and von François ordered his men to hold the road from there to Willenberg.

They formed a barricade across the line of retreat as Russian soldiers flowed in and out of the nearby woods. The Germans secured the rear group, who were exhausted from lack of rest and food. The hungry and exhausted men accepted their defeat, surrendering to the Germans in the tens of thousands.

Even Samsonov found himself wrapped up in the flurry of retreating men. Unable to stop the madness, he turned around and rode south, only to get lost in the dense forest. His absence had gone unnoticed until the early hours of August 30, when a lone shot rang out from the woods. Rather than admit to his failure, Samsonov shot himself with his officer’s pistol.

Even though the German contingent of 150,000 men was outnumbered by the Russians, who had 230,000, they still managed to nearly eradicate the entire 2nd Army. When all was said and done, only 10,000 returned to Russia. Between 30,000-78,000 were killed or wounded in the battle, while another 92,000 were taken as prisoners of war (POWs).

More from us: 37 mm M1916: The French ‘Bunker Buster’ That Became a Hindrance on the Western Front

Battles continued between the Germans and the Russian 1st Army Corps, who were also defeated and mostly destroyed. After the resounding success of the campaign, German Kaiser Wilhelm II named the battle after Tannenberg, a nod to the 1410 engagement that eviscerated German knights.