Billy Mitchell, a controversial figure in his time, is now known as the founder of the United States Air Force. Serving in World War I, he rose through the ranks, until he was commanding all air units in France.

In a position of power, he promoted the expansion of the US Air Force, as he thought this would be the wisest move going forward into future wars.

Later in his career, he was accused of being insubordinate to his leaders and was forced to resign. However, Mitchell received an array of posthumous honors and awards, and the North American B-25 Mitchell military aircraft design carries his name.

The Beginning of Greatness

Mitchell was born in France to a wealthy Senator and grew up in Wisconsin. He lived a privileged life, attending George Washington University before enlisting as a private in the Spanish-American War. He then used his father’s influence to gain a commission, joining the US Army Signal Corps.

After the Spanish-American War had ended, Mitchell stayed in the military as an instructor at the Army Signal School. There, in 1906, he began mulling over the idea of planes being used in warfare. His interest in air travel increased, and he was one of the few people to see the Wright brothers’ plane fly in Virginia, in 1908. He later took flight lessons in Newport News, Va.

In 1912, his military service gave Mitchell the chance to travel through Alaska and Asia, and he took the opportunity to learn about the Russo-Japanese conflict. It was then he predicted a future war with Japan.

Later, he served as a Signal Corps Officer on the General Staff. He was chosen to act as head of the Aviation Section, US Signal Corps, the group that would precede the current US Air Force.

World War I

Four days after the US declared war on Germany, Mitchell set up an aviation office in Paris. There he worked alongside British and French aviators. He was the first US officer to make a flight over German lines, accompanied by a French pilot.

He learned from these countries regarding aircraft and strategies. He was confident he could adequately conduct American air operations in France.

In 1918, he led more than 1,000 British, Italian and French aircraft during the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, one of the first coordinated air-ground offensives in history. His talents led him to take charge of all the American air forces in France. He was recognized as one of the most influential American combat airmen.

After the War

When he returned to the US in 1919, Mitchell expected to become the Director of Air Service. Instead, he was given an empty title. He was promoted several times until finally receiving an appointment as Assistant Chief of Air Service in 1921.

During his career, he held a belief not popular with many people; that WWI was not the war to end all wars. He predicted that air travel would make war and conquest easier than ever.

Mitchell pushed for more aircraft carriers for the Navy, an opinion that was highly opposed. He urged it was possible to develop the technology needed to create aircraft able to drop bombs capable of sinking battleships. Many people felt it was an unneeded advancement.

However, Mitchell was determined to prove his theory. Unfortunately, he verbally attacked his superiors in the War and Navy departments. He called them nearsighted regarding the need for wartime airpower and questioned their judgment.

In addition to aircraft capable of bombing battleships, Mitchell also wanted aerial torpedoes; aircraft that could operate in snow conditions; and aircraft that were able to fight forest fires and patrol borders.

He also wanted to stage an air race. A flight from one side of the country to the other, to encourage public attitudes to air travel. He urged military pilots to break any speed, altitude or endurance records possible.

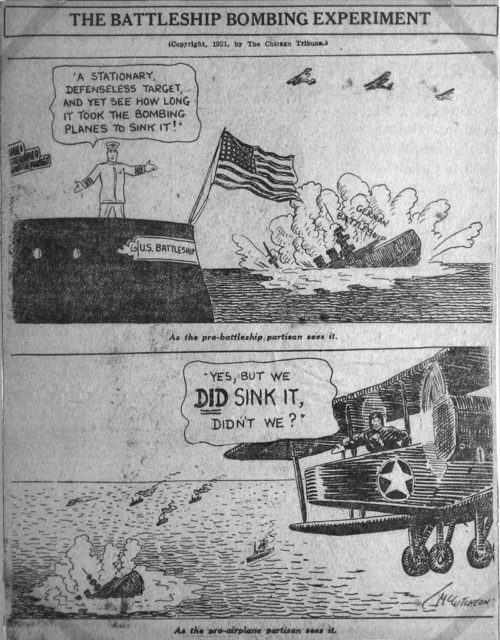

Mitchell convinced the Secretaries of War and Navy to attend a demonstration showing the destruction of ships by aerial bombing.

He was as convinced as ever that planes could defend America’s coasts for a fraction of the cost needed to build ships. The Navy and Army were not thrilled about the test. It could undermine either force but agreed to the demonstration after some arm twisting.

The rules for the trial stated the ships must be sunk into 100 fathoms of water about 50 miles off the Chesapeake Bay. The planes could not use aerial torpedoes; could only hit each ship twice, and small ships could not be hit with bombs weighing more than 600 pounds.

Additionally, between hits, attacks had to be halted so damage assessment groups could take a look at the results.

The test results were in Mitchell’s favor, with his men successfully sinking a destroyer G-102 and a light cruiser.

However, while the Ostfriesland did sink, the assessment team decided that a fast-acting crew onboard could have prevented it. Each side decided they had won the contest, but both the Navy and the President were upset at the weakness found within their naval force.

Career Aftermath

Mitchell continued to be critical of the official views on aerial warfare until he was eventually forced to resign due to internal conflicts. He turned his attention to promoting air travel in both his writing and speaking engagements.

He was a big fan of Franklin D. Roosevelt and met him to discuss his ideas for a Department of Defense. He had hopes that Roosevelt would name him either Secretary of War, or Assistant Secretary of War for Air, but neither happened.

Mitchell spent his last days on a large farm in Virginia, dying in 1936 after a long career of fighting for US air power.