In the First World War, the largest naval encounter was the Battle of Jutland, in which the mighty dreadnought warships of the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet clashed.

It was a naval battle of epic proportions, involving two hundred and fifty ships, all of which featured the cutting edge technology of the time and the biggest guns ever used in a naval encounter up to that point.

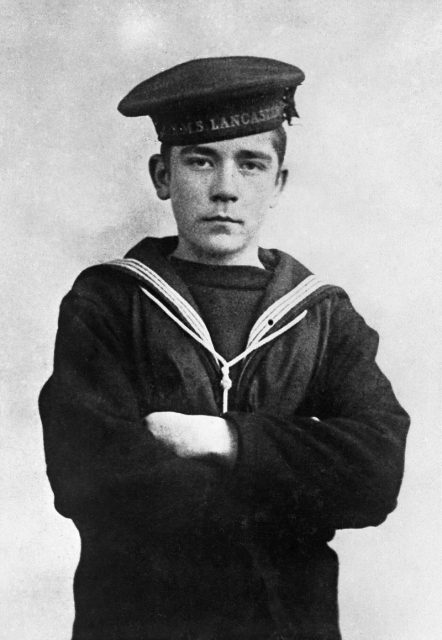

One hundred thousand men fought in this enormous engagement, and one of these was a sixteen-year-old English boy, John “Jack” Travers Cornwell.

Although he did not survive the battle, he was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for his outstanding courage in the face of mortal danger and terrible wounds, and his unfailing commitment to duty. Furthermore, he would end up being remembered as one of the most famous teenage servicemen of WWI.

John Cornwell was, by all accounts, not a particularly remarkable boy growing up in East London. He came from a humble background, with a father who had served as a soldier for a time, but who worked various blue-collar civilian jobs such as being a milkman and a tram driver, and a mother who was a housewife.

John did not stand out at school, nor did he win any accolades in any sports, but one activity at which he did excel was Boy Scouts. He won a number of badges, including one for helping others, and his experiences in the Boy Scouts no doubt prepared him for his next challenge in life: serving in the military.

Like many working class teenagers of the period, Cornwell abandoned school at a relatively early age to seek work. He wanted to join the Royal Navy, but as he was only thirteen when he left school, he had to take a job as a delivery boy instead.

However, when Great Britain entered WWI in 1914, this provided Cornwell with an opportunity to get into the military. In 1915, at the age of 15, he enlisted in the Royal Navy.

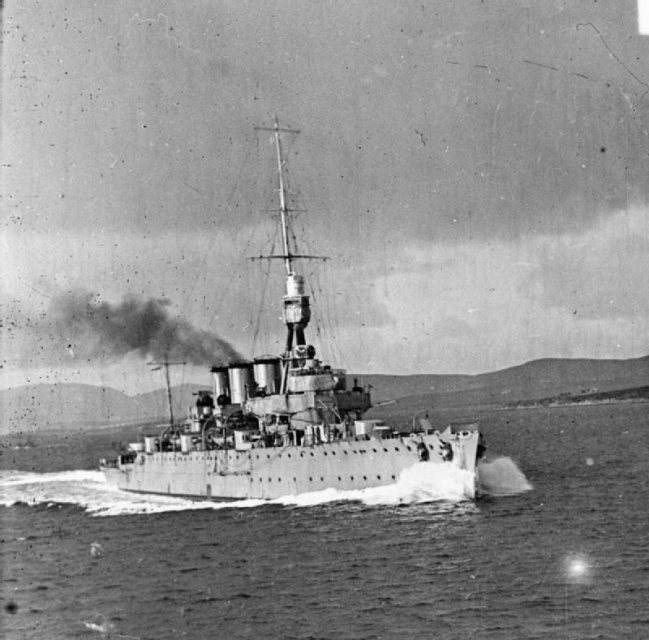

He took to navy life like a duck to water, doing well in his training and indeed excelling at seamanship and gunnery. He attained the rank of Boy First Class in February 1916, and in May 1916 completed his training. Cornwell then became part of the crew of HMS Chester, a light cruiser that was part of the British Grand Fleet.

Just a few weeks later, Cornwell and Chester would find themselves in the thick of the greatest naval battle of the entire war.

On Chester, Cornwell’s role was sight-setter for the ship’s forward 5.5 inch gun. This was a crucial position, and a very dangerous one too, as he would be largely exposed to enemy fire.

His responsibilities included adjusting the gun’s sight-setting disc, as well as relaying the gunnery control officer’s orders to the crew of the gun – and he performed all of these duties with excellence and dedication, as was seen when the ship entered the fray.

HMS Chester was part of Rear Admiral Horace Hood’s 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron. On the day of the battle, 31 May 1916, Chester was five miles ahead of the rest of the battlecruisers, which in turn were twenty-five miles ahead of the rest of the fleet, scouting the waters of the North Sea.

Chester was ordered to investigate a number of gun flashes to the southwest of the British fleet, and when the ship did, she found herself trapped by four German light cruisers.

There was no other option for the British ship but to stand and fight, despite being heavily outnumbered and badly outgunned. Despite a valiant attempt to assault the German ships, within minutes all of them were bombarding Chester, and most of her guns and crews were taken out within minutes.

Among the gun crews destroyed by the ferocious German bombardment was John Cornwell’s. His gun took a direct hit, and almost the entire crew was killed – except for Cornwell and two other sailors.

Even though he was alive, he was horrifically wounded, with shards of shrapnel skewering the teenager’s legs and impaling his stomach.

Despite the chaos on deck, though, with German shells raining down and the British dead and wounded and broken guns scattered everywhere, young John Cornwell remained steadfast at his post, awaiting orders.

Somehow, Chester’s captain, Robert Lawson, managed to steer the ship out of the fight, and despite taking seventeen direct hits and losing seventy crew members, the ship remained afloat. Only after Chester had exited the battle did the severely injured John Cornwell finally leave his post.

Like many other badly wounded troops, there was little doctors could do for him, and he succumbed to his wounds and died two days after the battle, on June 2, 1916. He was given a quiet, anonymous burial, and his brave stand was almost forgotten.

However, when Admiral Beatty printed a dispatch on the battle in a British newspaper in July 1916, he mentioned John Cornwell’s valiant stand, and what happened next was the early twentieth century equivalent of “going viral.”

Suddenly, articles about John Cornwell started to pop up in newspapers all across Britain. In the wake of the carnage of the war, the British public was desperate for stories of heroes, and John Cornwell’s tragic story hit just the right chord.

In response to a massive public demand to have Cornwell’s actions at Jutland honored, his body was exhumed and he was given a hero’s burial, in what was one of the largest public events of the whole war.

He was then posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross on 15 September 1916, and 21 September 1916 was designated as “Jack Cornwell Day.”

Postage stamps with his picture on them were sold, and various benefit funds were set up and named after him. One of these enabled the construction of a new ward for wounded sailors at the Star and Garter Home in Surrey.

In the Boy Scouts, the Cornwell Scout Badge was created, and awarded to scouts for valor and bravery.

Read another story from us: Battle of Jutland – Won by the Numbers

Despite the huge public following and the nation rallying behind the boy’s name, things didn’t go so well for his family. His father died a mere month after it was announced that John would be receiving the Victoria Cross.

His mother saw little of the money raised in her son’s name, and died in poverty in 1919. Nonetheless, John’s memory lived on, and to this day he is remembered as the boy hero of the Battle of Jutland.