Though not as well remembered as the Somme, the Battle of Loos was one of the British Army’s great humiliations of the First World War. Launched to support a French offensive, it ended in heavy losses, little gain, and the removal of the British commander-in-chief.

The Autumn Offensive

In the autumn of 1915, Marshal Joseph Joffre, the French Commander-in-Chief, planned a great offensive against the Germans. It consisted of two distinct attacks at the same time. France would attack the German lines in the Champagne region, while an Anglo-French force went on the offensive in north-easterly Artois.

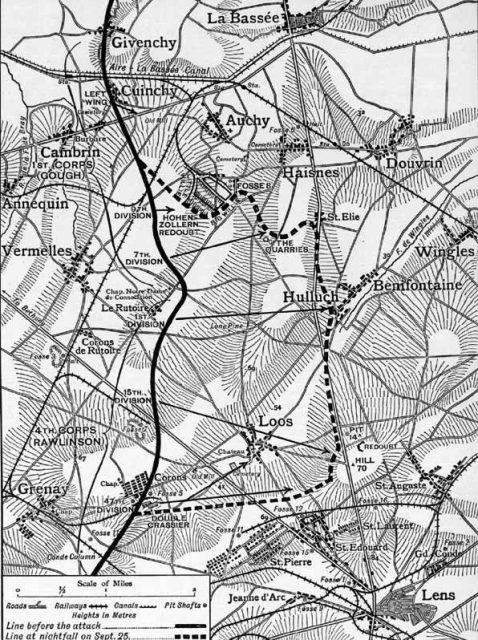

The Artois offensive was further divided into two parts, forming a pincer movement. While the French attacked Vimy Ridge, the British would seize the town of Loos and the surrounding area.

The overall aim was to capture strategically important railways and force the Germans out of the Noyon salient, liberating a portion of occupied France.

Preparations

Field Marshal Sir John French, the British Commander-in-Chief, was not impressed with the plan. His men would be attacking ground full of mines and miners’ cottages, which would make good defensive positions for the Germans.

His reservations were over-ruled by Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, who insisted that they support Joffre’s plan even if it came at a high cost.

As he prepared for the battle, French’s attitude towards it improved. This would be his first chance to use chlorine gas on a large scale, a potentially powerful new weapon.

Command of the attacking forces was given to General Sir Douglas Haig. He was assigned six divisions divided into two corps. But French did not give Haig’s authority over the reserves, probably to keep Haig from committing them too early.

As usual, the attack was preceded by a heavy artillery bombardment. Such barrages were never as effective as they were meant to be, and this one was made weaker by a shell shortage. Meant to soften up the Germans, it did them little harm, as they took shelter in their dugouts. What it did achieve was to warn them that an attack was coming.

Attacking Loos

Early on the 25th of September, the attack began. Chlorine gas was released from canisters on the British side of the battlefield. A weak wind carried it into no man’s land. Instead of reaching the German lines it stopped in the open, blocking the view and complicating the British advance.

75,000 soldiers set out across the blasted and gas-shrouded ground. They outnumbered the Germans, and if the artillery and gas had lived up to their promise then they would have had an easy time. But in the First World War, these weapons never lived up to the hype.

On the far side of the battlefield, the British found that much of the German wire had not been cut, large areas of defenses were intact, and the Germans had emerged from cover to man the lines. As often happened in the First World War, men advanced straight into a hail of gunfire and were cut down in droves.

Sheer weight of numbers still had its benefits. The British captured the town of Loos before grinding to a halt just beyond.

Things Fall Apart

Having withheld his reserves, French now decided to hand them over to Haig. But these troops were far from the front line. They marched for hours to reach Loos, arriving hungry, tired, and soaked from the rain. Most of them were inexperienced soldiers about to see real battle for the first time.

Meanwhile, the advance had left the fighting troops with disorderly supply lines, making it hard to bring up fresh men, bullets, and food.

On the morning of the second day, the British launched a new attack. They showed no signs of having learned from the previous day’s debacle, or from any of the fighting of the preceding year. Advancing in the open as a solid mass, the troops were again stalled by barbed wire and became easy targets for the Germans. Of 10,000 men in this second wave, 8,000 were killed or injured. The Germans emerged unscathed.

The Germans now counter-attacked, driving the British from recently taken ground. Weeks of back and forth fighting commenced. At times, British soldiers found themselves driven back to their starting positions, forced to assault the same German trenches over again.

As September turned into October, rain, exhaustion, and flagging morale took all the impetus out of the fight. The battle officially ended on the 4th of November.

Aftermath

The British suffered over 60,000 casualties during the Battle of Loos. These included many fine young officers, who went to their deaths at the heads of their units. Three major generals were among the fallen. So was the only son of Britain’s foremost patriotic poet, Rudyard Kipling.

In exchange for these heavy losses, the British had inflicted around 20,000 casualties on the Germans. They had taken Loos but little more. The great pincer movement to link up with Joffre and the armies of France failed.

Heavy losses at Loos convinced the government that it needed to recruit troops more quickly. Kitchener estimated that 35,000 men a week were needed to keep units at strength. While there was some exaggeration in this, the need to increase recruitment was clear.

Haig made the most of the fiasco to advance his career. Using official papers, he demonstrated that blame for the failure lay with French as commander-in-chief, not with himself as commander of the attack. This evidence went all the way to the king. French was removed from command and Haig took his place.

For someone at least, Loos brought good news. But it came at a hellish cost.