Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck faced the most challenging task of any German commander in the First World War. In Europe, the Germans were confident of their military might. They had strong armies, extensive training, and detailed plans on their side.

However, in East Africa, where Lettow-Vorbeck was based, it was very different. Britain was the strongest colonial power, with Germany lagging behind.

Lettow-Vorbeck Arrives

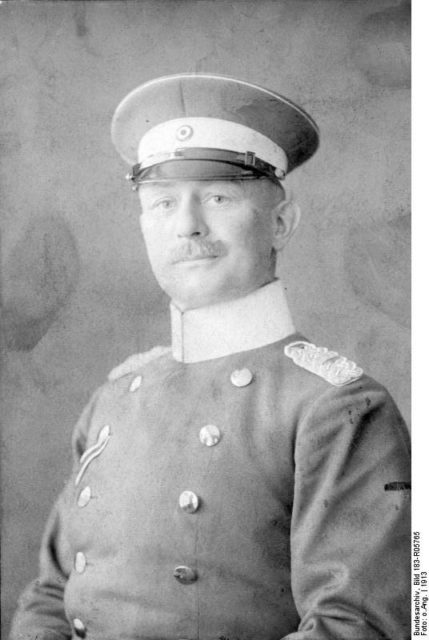

In January 1914, as tensions rose across Europe, Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck arrived in Dar es Salaam. He was taking over as commander of the colonial forces in German East Africa.

The Germans had held the territory for only 30 years. It was vulnerable to British attack, and there was much talk of what would happen there if war broke out.

Lettow-Vorbeck reconnoitered his new command. He realized that, with only a few hundred European and 2,000 local Askari soldiers at his disposal, he could not defeat the British. However, he believed he could best serve Germany by tying the British down in a long war, keeping their troops from the Western Front.

He reorganized his soldiers into small independent companies, ready to fight a guerrilla war.

Tanga

Following the outbreak of the First World War, there were brief border skirmishes with British troops. Then the first substantial British force arrived on November 2, 1914, off the coast at Tanga. A major port and terminal of the rail line, Tanga was a vital supply and communication hub.

The British had greater numbers and much better equipment, but they were poorly led. Between Lettow-Vorbeck’s dynamic leadership and the disastrous failings of the British, the Germans achieved a decisive victory. They seized British equipment, setting them up for the war that followed.

The Long Haul

Lettow-Vorbeck prepared for a long, grinding campaign. He set up bases in the bush and found alternative resources to keep his army supplied. While building up his supplies and transport, he launched attacks on the British, destroying bridges and stealing their supplies. He seized enough horses to form a mounted company.

In early 1915, he beat the British in a battle at Jassin. He lost as many soldiers as them, losses he could not afford so he went back to guerrilla fighting.

The Tanga Railway Advance

In February 1916, the British began a significant advance. Reinforced with fresh troops, they made a two-pronged offensive, one prong of which was along the vital Tanga railway. The British hoped to encircle Lettow-Vorbeck, who saw the risk and pulled back rather than be cut off.

The campaign was made difficult for both sides by the densely-grown bushland in which communication was difficult. It was made easier for the Germans by support from local planters, who kept them supplied.

A Fighting Retreat

Throughout his campaign, Lettow-Vorbeck’s approach was that of a slow fighting retreat. It allowed him to engage many British and colonial soldiers without the risk of being cut off or facing a battle against overwhelming odds.

When a large South African contingent was pulled out in late 1916, its commander reported they had taken territory from the Germans; but Lettow-Vorbeck was still at large.

Withdrawal South

While some British troops departed, others arrived – respected veterans of fighting in West Africa. Their arrival kept the Germans on the defensive. In September 1917, Lettow-Vorbeck’s forces captured a supply of weapons and ammunition from their opponents. However, in the same month, heavy casualties forced them to abandon their headquarters and continue their southward withdrawal.

Bloodying the Enemy

October 1917 saw Lettow-Vorbeck’s most substantial single victory since Tanga. Carefully choosing a strong defensive position, he held up the advancing enemy for four days, inflicting thousands of casualties and capturing supplies, including machine-guns.

Despite this, he was running low on bullets, food, and medicine. He could not keep a large fighting force in the field.

Rovuma Valley

On November 21, Lettow-Vorbeck assembled a force of 2,000 soldiers and 3,000 bearers. With this group, he headed up the Rovuma valley on what would become a long and effective raid.

The valley marked the border between German and Portuguese territory. Living off the land and captured supplies, the Germans attacked the Portuguese garrison, defeating them soundly in an early battle.

As the British moved in, Lettow-Vorbeck fought on both sides of the border, his guerrilla campaign causing grief for both his enemies. It was only at the start of 1918 that they began to cooperate, putting pressure on the Germans.

Heading Home

After months of southward travel, Lettow-Vorbeck faced an important decision. If he continued, he would run up against the Zambesi river. A crossing would be impossible, and he could become trapped.

He turned north. Although he often evaded his pursuers, there were skirmishes, and in September 1918 he suffered over 100 casualties fighting a British force.

His exhausted troops were abandoning the campaign and an influenza outbreak ravaged those who remained. A build-up of British forces threatened tougher battles but he kept pushing on.

Armistice

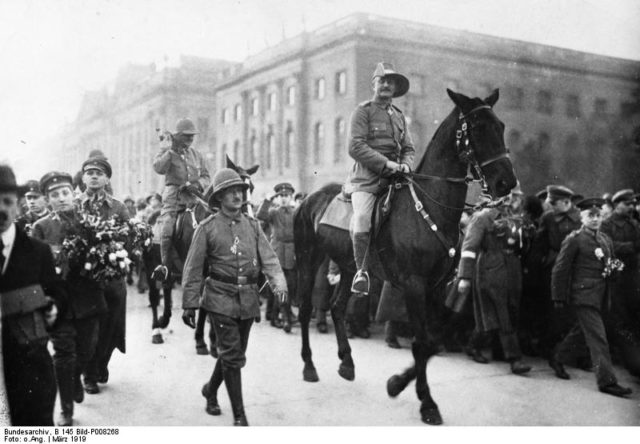

On November 12, a British despatch rider reached the German HQ. He brought important news; an armistice had been signed, the war was over.

It was a tough moment for Lettow-Vorbeck and his officers. With little news from Germany, it was hard to believe how badly things had gone.

Lettow-Vorbeck was welcomed back in Germany as a hero. He had led the British in a merry dance all over East Africa, inflicting thousands of casualties. The Germans had lost the war, but for his part, Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck was a victor.

Source:

Geoffrey Regan (1991), The Guinness Book of Military Blunders.

David Rooney (1999), Military Mavericks: Extraordinary Men of Battle.