For the German troops near the French town of Cambrai, the world exploded into terror and flame on the morning of November 20th, 1917. 1,003 guns of the British army opened in unison at 6:10 AM that day, in an intense and destructive barrage which lasted only ten minutes. It was quickly followed by one of the most terrifying sights anyone could have imagined.

As the early morning fog rolled through what was once farmland, but was now desolate earth, thundering steel beasts followed in its wake. The German troops that morning awoke to find themselves facing an entirely new type of warfare: a massed tank assault.

This battle was the brainchild of John Fuller, commander of the British Tank Corps, and Sir Julian Byng. Fuller and his supporters in the British Army Staff convinced Byng that an armored breakthrough was the only substantive way to break the stalemate of the first world war. Byng was convinced, and secretive planning for a surprise attack was put into motion.

The town of Cambrai was chosen as this attack’s objective. Cambrai was an important supply line junction for the German army in the region, connected by both rail lines and river. It also had fairly open land in front, necessary for a massed armored assault. But what was most important was that it was a reachable distance from Byng’s section of the line.

Building up to the battle, the British began massing troops behind their lines. They slowly moved up their new Mk. IV tanks, running them in low gear. While this meant that all progress was slow, it also meant that they were much quieter. To cover any possibility of detection by noise, the British flew constant aerial sorties up and down the German line. This had the added effect of giving them an up-to-date view on German positions and holdings. Finally, by the 19th of November the British 3rd Army, and the 473 tanks they accumulated, had readied themselves. Unbeknownst to most of the men there that day, warfare would change the next morning forever.

The bombardment opened up at 6:10 AM, with the tanks and infantry advancing at 6:20 AM. Even the bombardment was a display of new technology. By teaching their artillerymen and NCOs ballistics, and some of the more complicated mathematics behind calculating bore wear (which limited the range of artillery guns) the British were able to fire accurately without the need for ranging shots. This meant that when their guns let loose their first volley, they were on target without any indication that a bombardment was coming.

As the barrage crept forward, it was followed by continuous waves of tanks and infantry. This was the first mass armored assault of the war, and no one was entirely sure how it would go. Prior attempts to use tanks decisively had often proved disastrous. Often used piecemeal and only in support of massed infantry, the tanks were exposed. German artillery, or even troops with specialized hand grenades, were able to pick off any tanks which got too close, and then they would simply mop up the remaining infantry. But at Cambrai, the tanks just kept coming.

As this mass assault pushed forward, the tanks crushed the wire, and pounded the German defenses. While the German troops retreated in the face of these beasts the British infantry would pour into the lines. Finally, the front lines had been broken, and the British began pushing for their initial objectives before they pushed forward to the town of Cambrai proper.

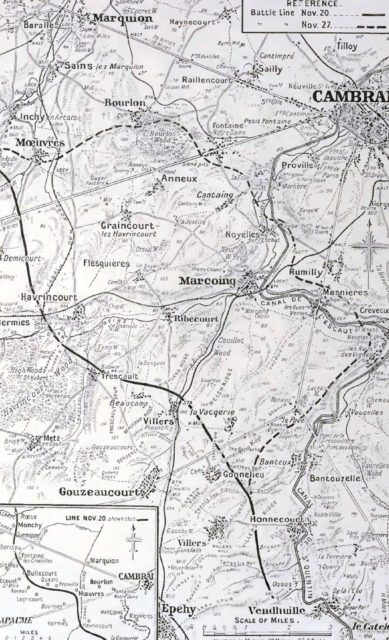

Of the six British infantry divisions present on the first day, five took their objective on the first day of fighting. The 12th took the Lateau woods to the south, starting a defensive line which allowed the fast moving cavalry to push forward. The 6th Division pushed to Marcoing, securing the front line facing Cambrai. The 62nd pushed forward to just in front of Bourlon wood, and the 36th secured the northern flank. The 20th Division, supported by tanks and cavalry took Masnieres and La Reus Vertes. The 51st division was the only one not to, being initially pushed back at Flesquieres, which left a German salient in the advance. This was later swept up by other infantry and cavalry.

But the 20th division’s advance bore witness to the first major mistake of the battle. A tank – ironically named “flying fox” – attempted to cross the Canal de L’escaut. As it rumbled across the bridge, it did anything but fly, crushing the bridge beneath it. This held up an entire cavalry division who were tasked with pushing through the now weakened lines and around Cambrai proper. Their inability to circle the main objective meant that the German troops had an uninterrupted approach to front lines, which would become vital for their regrouping in the coming days.

By the end of the first day, the British troops had advanced an astonishing five miles into one of the hardest points of the Western Front. Unmatched by any other major western assault since the start of the war, this must have seemed miraculous to the troops there. It was clear to them that tanks were the trump card they had been waiting for. But things quickly went downhill for these men.

Over the next ten days, these amazing advances would crumble in front of the very men who had won them. The British high command was focused on capturing Cambrai at all costs and continued to push forward. Over 100 tanks had been wiped out on the first day of combat, and they were never used in a true combined arms sense after that assault. Instead, troops would advance with a small tank support, or limited artillery, as the guns were still being pushed forward into new firing positions. Finally, the British decided to consolidate their victories and dug in on the 27th of November.

The next day the German counterattack began, hitting Boulon wood with gas followed immediately by infantry. Later, on the 30th they hit the sides of the British salient, hoping to cut off the head. They employed a new infantry tactic, using light infantry to bypass any hard points or machine guns, rather pushing forward to destabilize the enemy. This cut off the rear defenses and prevented an orderly retreat. After the initial light infantry, heavier troops would follow up to knock out the hardpoints and secure any gains. This proved to be an incredibly effective tactic, and in a few days, the British were pushed back to their lines from before the November 20th assault.

While the Battle of Cambrai was strategically insignificant, it proved an experimental success, both for the use of tanks and of infiltration tactics. Looking forward to 1918, the Second World War, and even modern conflicts, one can see the everlasting echo of Cambrai. Tanks became commonplace on the battlefield, especially combined with Infantry, artillery, and airpower.

The German spring offensive in 1918, although doomed from the start due to lack of resources and manpower, employed the infantry lessons of Cambrai: constant fluid motion, bypassing the better-defended areas. And every successful armored assault since then has shown that tanks need three things: infantry, to protect them from counterattack, airpower to protect them from the skies, and numbers, to overwhelm and overpower the enemy. Unfortunately, tactical innovations rarely come without great cost. Between the 20th of November, and the 7th of December 1917, the British lost 44,000 men and 173 tanks, the Germans lost 45,000 men.