War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America and is the author of “Together as One: Legacy of James Shipley, World War II Tuskegee Airman,” availabe at www.missouriatwar.com.

In many states, farmers bore the brunt of responsibility in World War I—not just from the perspective of producing the food that would be used to feed the soldiers of the United States military, but also by leaving their farms and families when drafted into military service. The late Gustav “Gus” Buchta, a Mid-Missouri farmer, embraced this responsibility and went on to carry the wounds of war in the years following his return from France.

Born in Russellville, Mo., on August 27, 1893, Buchta became the sole support for both his mother and his sister, and, as noted on his registration card, was engaged in farming when he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917.

The 24-year-old’s life quickly changed because of the Selective Service Act of 1917. As reported in the July 20, 1917 edition of the Jefferson City Post-Tribune, the numbers of “Many young farmers (were) drawn” including Buchta’s—an event, the article further noted, that “will about complete Cole County’s quota of 189 men.”

“He never talked about the war, that I ever heard,” said Dorothy Rockelman, Buchta’s stepdaughter. “Then again, he wasn’t the only World War I veteran who didn’t talk about what all they went through.”

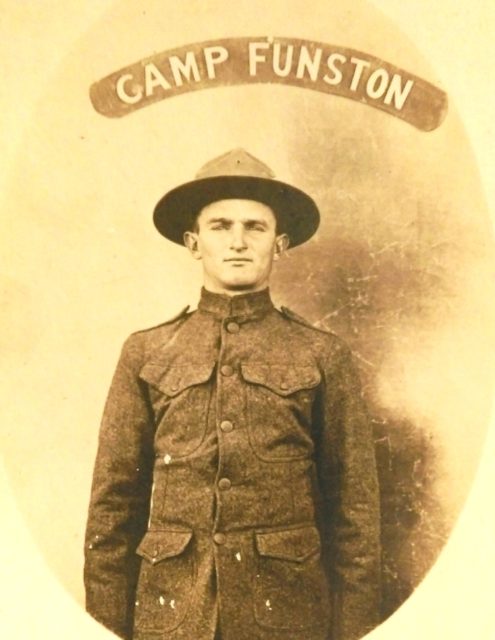

The farmer’s service during the war begins to come into focus through several records, such as his service card available from the Missouri State Archives. Inducted into the Army on September 20, 1917, Buchta began his military service as part of Company M, 356th Infantry under the 89th Division.

“The 356th Infantry was composed of men from the State of Missouri, ‘M’ Company composed chiefly of men from Cole, Boone, Henry, Andrews, St. Louis and Jackson Counties,” as is noted in an official history of the company.

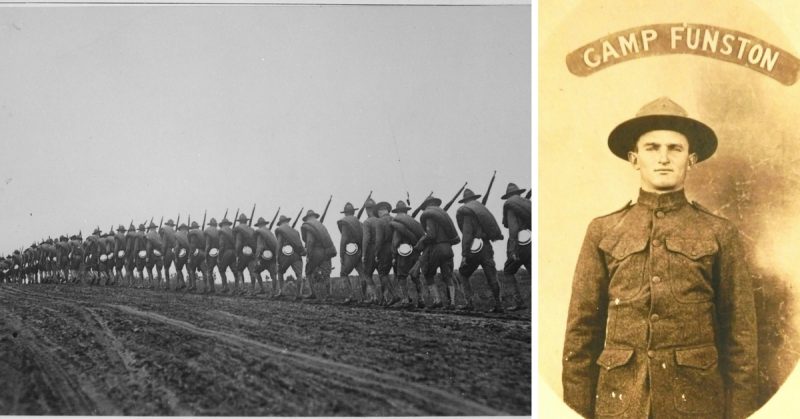

The men of Company M trained for several weeks at Camp Funston, Kan., where Major General Leonard Wood was serving as commander. However, as stated in a history of the 356th Infantry, in “November (1917) and the four months following, men were selected from the company to go with other units for advanced overseas service.”

Buchta was transferred to a replacement battalion with whom he deployed to France in late March 1918. Several weeks later, he was reassigned to Company A, 126th Infantry Regiment—a National Guard regiment from Michigan that had been reorganized and assigned to the 32nd Division.

When Buchta joined the regiment, they had been in France for nearly two months. On May 14, 1918, the regiment left their training area and “prepared to take its place in the long battle line extending from the English Channel to the borders of Switzerland, where it was destined to stay until the end of the war, except for a brief ten days in the month of September,” noted the book “History of the 126th Infantry in the war with Germany.”

The regiment received instruction on trench warfare from their French counterparts who had been fighting the war for nearly four years. The 126th Infantry entered the trenches in early June 1918 and began a cycle of service on the front lines, enduring gas and shrapnel shells launched by the German forces in the Alsace region of northeastern France.

On June 25, 1918, two days after the Germans made their first raid against the lines held by the 126th Infantry, Buchta was wounded in action.

“He was hit by shrapnel, “said Dorothy Rockelman. “I know that he received some disability from the government for it after the war and eventually walked with a cane because of the injury. In later years,” she added, he had to use two canes to get around.”

Though it is uncertain how long Buchta was in the hospital for treatment of his injuries, his service card indicates he remained with the 126th Infantry through several deadly engagements including the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

Following the armistice on November 11, 1918, “there began to straggle through our lines in a steady stream, repatriated prisoners from the French, Russian and Italian armies … poor forlorn-looking creatures … grateful for the smallest of favors …” as was written in the regimental history.

The men of the 32nd Division soon became part of the American Army of Occupation, marching across Luxemburg and crossing into Germany. The division remained in Germany until mid-spring 1919; however, Buchta was sent home in mid-December 1918 and was discharged from the Army on May 8, 1919.

“He got a disability from the service because of his combat injuries,” said Rockelman. “After the war, he lived with his mother and did some farming, and,” she added, “in the 1950s, he worked as a janitor at the Russellville School.”

As Rockelmen further explained, on April 24, 1952, her mother, Lydia Hiemeyer, was married to Buchta and the couple remained members of Trinity Lutheran Church in Russellville. The WWI veteran passed away in 1977 and was laid to rest in Trinity Lutheran Cemetery near Russellville.

Rockelman realizes that although her stepfather accepted the responsibility given him during the First World War, she knows little of his personal combat experiences. Yet several archival sources provide a glimpse into the willingness of Buchta and his fellow farmers to serve their country, and their contributions both during and after the war.

On April 23, 1917, former Missouri Gov. Frederick Gardner held a war conference at the state capitol, stating, “Look, if you will, from the dome of this great building, across the millions of acres of the finest farm lands over which the eagle has ever spread his wings.”

Acknowledging those who would soon make robust sacrifices on behalf of Missouri, Gardner added, “Look again, and you will see the man: There is the patriot; there he stands, the farmer … the mother in the doorway; the daughter by her side … ready, if the country calls, to see the father and the son go to defend the nation’s honor.”