The First World War saw unprecedented death and destruction all along the Western Front. Despite this, soldiers from opposing sides managed to have friendly encounters, finding their common humanity among the divisions and brutality of war.

Shouted Conversations

With the trench lines often close together, it was common for soldiers to have shouted conversations with men in the opposite line. Denis Barnett of the 2nd Leinster Regiment wrote about a conversation he had which started with a German shouting “Guten Morgen, Allyman” at dawn. Barnett returned the greeting, followed by some comments about the German Kaiser. Soon the two were exchanging insults, the German showing off his knowledge of English obscenities. Many of the café and restaurant staff in pre-war London had been Germans, and so the conversation ended on a mocking reference to earlier times, with Barnett calling out “Waiter!” and the German replying “Coming, sir.”

Barnett’s conversation captured the tone of these exchanges, which ranged from polite pleasantries to insulting banter. Even when there was firing in the night, the two sides would sometimes call out, mocking each other’s marksmanship or singing songs.

Nodding in the Night

One of Barnett’s men had a more direct encounter with the enemy. Sneaking out unarmed and without permission to take chickens from a ruined farm, he ran into a German doing the same thing. Rather than interrupt their foraging for a messy unarmed brawl, the two men nodded to each other and walked on.

The Christmas Truce

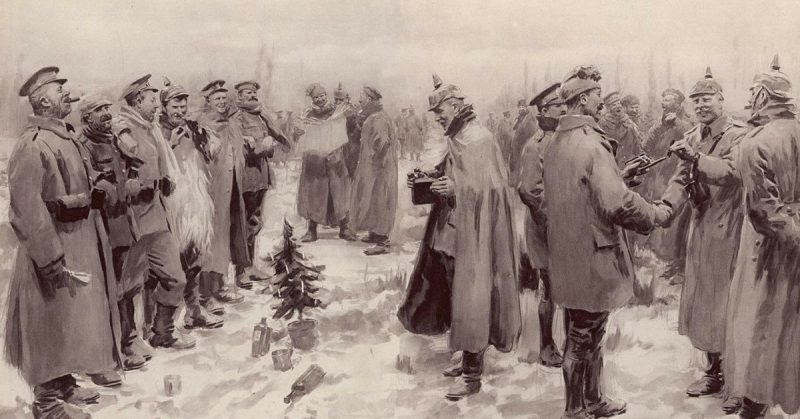

On Christmas Day 1914, bishops in England preached about the unfortunate necessity of war while in Rome the Pope called for a truce between the belligerent nations. Unaware of any of this, soldiers in the trenches of the Western Front created their own unofficial peace.

One of the best accounts of this truce comes from Frank Sumpter of the British 1st Rifle Brigade. In his part of the line, singing in the German trenches was followed by shouted greetings and signs wishing the other side a merry Christmas. Finally, a brave German soldier stood up on top of the trench works to call out to the British. Soon men from both sides emerged and went to meet each other on the shell-blasted soil of no-man’s-land.

Many of the Germans spoke English, having lived and worked in large British cities such as London and Manchester prior to the war. Men from opposing sides discovered that they had lived and worked within streets of each other. News, rumors, and supplies were exchanged. German soldiers who had once been barbers shaved English infantry who had once been clerks and laborers. The terrible business of war was left un-discussed as men avoided facing the violence between them.

In some parts of the line, this unofficial truce lasted for several days. One of the longest was between the 1/6th Gordon Highlanders and the Germans opposite them. It was only on the 3rd of January that the Germans received orders that they had to start fighting again. One of their officers marched out between the lines and met with a captain from the Highlanders. Between them, they arranged a time to re-start the hostilities. Forced to start fighting again, they did so with as much honor and friendship as orders allowed.

Captain Campbell’s Parole

Badly injured at Mons in August 1914, Captain Robert Campbell was captured by the Germans. After spending nearly two years in Magdeburg prisoner-of-war camp, he received news that his mother was dying.

The commandant of Magdeburg encouraged Campbell to write to the Kaiser, asking for special dispensation to return home and visit his dying mother. Thanks to the commandant’s help, the letter not only got through the chain of command but received a favourable reply. Campbell was given permfavorableleave the camp, travel home and spend two weeks in England, as long as he promised to return to incarceration in Magdeburg.

Good to his word, after visiting his mother, Campbell returned to Magdeburg. Sadly, the British did not follow the example of the Germans and refused all similar requests. As a result, Captain Campbell’s parole remained unique.

Exchanging Souvenirs

When the 1/5th Seaforth Highlanders took over positions on the Somme, they found that the French, who had previously occupied these trenches, had extremely friendly relations with the Germans. On the first day, they found a note amid the barbed wire inviting two or three men to meet a similar group of Germans in no-man’s-land at a set time. There they could exchange souvenirs and periodicals, as the Germans had done with the French. The meeting went ahead peacefully, watched by men from either side in the trenches.

The British commander was less than impressed. He severely reprimanded the Highlanders for their actions, saying that they could not fight men with one hand who they were giving presents to with the other.

Sharing Tools

The German Saxons, aware of their hereditary linked with the Anglo-Saxon English, were among the friendliest faces peering across the lines. In January 1915, with large working parties constructing defenses on both sides, the Saxons shared a heavy hammer with the British East Kent Regiment. The hammer was thrown back and forth across the barbed wire, as each army took its turn with the tool.

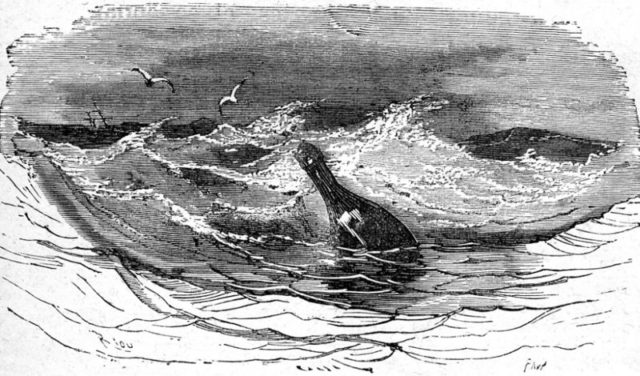

Messages in Bottles

The Saxons were also responsible for one of the most unlikely forms of communication in a war on land – messages in bottles. With streams running from them down to the lines of the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, some of the Saxons wrote friendly messages and put them in empty bottles, which they then put in the stream to float down to the British trenches. More than anyone else in the war, they seem to have felt a sense of all being in it together, regardless of nation.

Source:

Richard van Emden (2013), Meeting the Enemy: The Human Face of the Great War.