The beginning of WWI was dictated by carefully developed strategies and their failure in the face of reality. The diplomatic and strategic plans of the belligerent nations were closely tied, meaning their policies helped to provoke the war.

What were those strategies?

Austria-Hungary

The Austro-Hungarian military had two plans for how to spark off a war.

Their first plan was for a localized war in the Balkans. They would bring their superior force to bear against Serbia, quickly overwhelming the smaller nation. It was the plan they intended to follow when they sent an ultimatum to Serbia on July 23, 1914 – an ultimatum the Serbs could not possibly accept. It was meant to give the Austro-Hungarians the war they wanted. When they did not receive the total agreement demanded, they declared war on the 26th.

However, the declaration of war set the diplomatic dominos falling, drawing the rest of Europe into the war. As a result, Austro-Hungary was forced to fall back on its other plan. It involved co-operating with Germany in a war against Russia and Serbia. Austro-Hungarian troops would invade Russian Poland to take pressure off the Germans in East Prussia. It would create a fighting front that ran the length of eastern Europe.

Belgium

Belgium was not a powerful nation. To withstand the expected German invasion, it would have to rely on geography and its allies.

The Belgian plan was to defend the frontier for as long as possible. When they would be inevitably overwhelmed by German numbers, Belgian troops would fall back into a series of fortifications designed by General H. A. Brialmont in the second half of the 19th century. If the fortifications at Liège and Namur fell, they would fall back to Antwerp. It was the national redoubt and the area where they would make their final stand until their allies arrived to rescue them.

Britain

Britain’s military was different from that of the other great powers. Although no less powerful militarily, Britain put far more emphasis on its navy. Their army was much smaller than those of continental Europe, and a significant part of it was committed to holding colonies elsewhere in the world.

As a result, Britain’s war plan fell into two parts.

One part was the British Expeditionary Force. The relatively small army would be quickly transported across the Channel to France. There it would line up on the left flank of the French where it could protect the Channel ports.

Meanwhile, the Royal Navy would blockade Germany. By cutting off supplies by sea, they intended to cripple German industry and so its capacity to wage war.

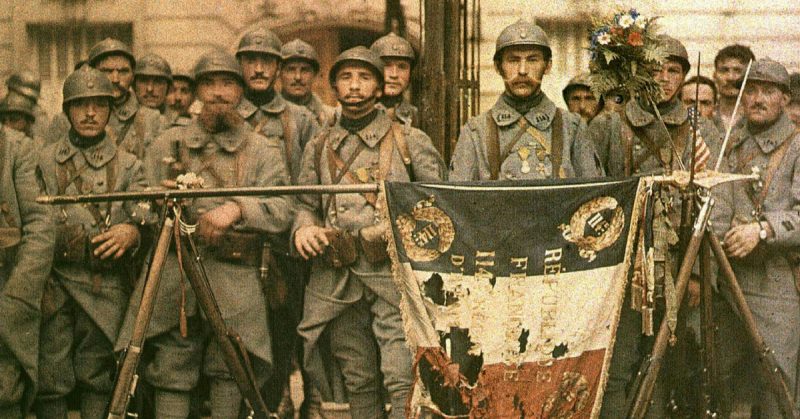

France

France’s strategy had been shaped by the bitter sting of defeat. In 1871, following German victory in the Franco-Prussian War, Germany had taken the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine from France. The French were determined to get those areas back.

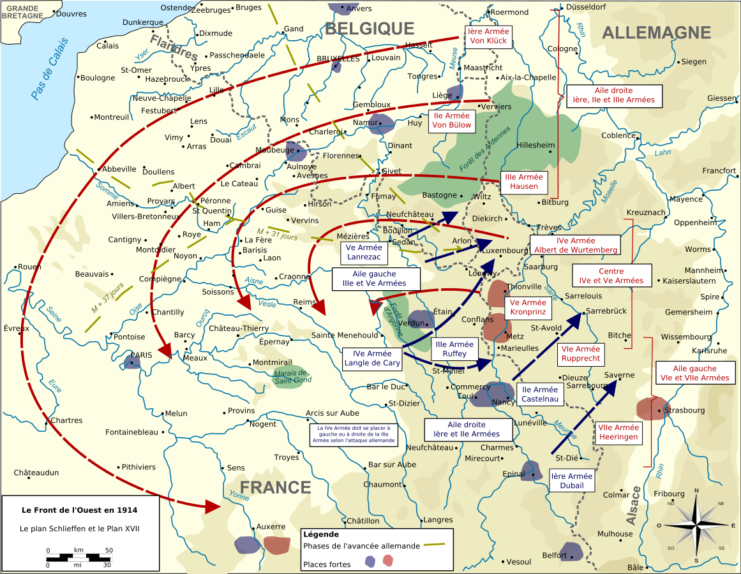

Devised by Marshal Joseph Joffre, Plan XVII called for French armies to muster on the border of the lost provinces. They would then strike aggressively into Germany, retaking the ground.

It was a plan that would leave the French left flank vulnerable. Joffre counted on the Germans becoming dangerously over-extended if they moved past the River Meuse.

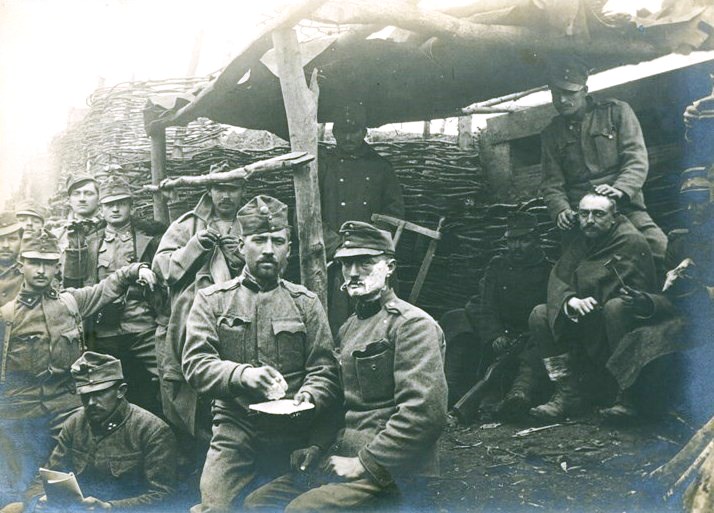

Germany

The German strategy had initially been developed in the 1890s by Count Alfred von Schlieffen and was updated by Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke.

Politics had shaped the Schlieffen plan. It assumed France and Russia would back each other up, meaning that if there were a war, Germany would have to fight them both. To avoid a war on two fronts, the Germans planned to attack France first, while Russia was still mobilizing. Through swift movement and a carefully planned timetable, they would move much quicker than the French. They would outflank their enemies with an attack through the Low Countries, force the French to surrender, and then turn to face east.

Moltke’s modifications watered down the plan. Russia had become more capable, and Moltke was not willing to let the Russians take part of Germany while he fought France. He, therefore, planned to leave a significant portion of the German forces in the east. He also decided not to invade the Netherlands, sending the entire western flanking force through Belgium. He hoped that by doing so and not invading the Netherlands, he could avoid British intervention.

Russia

Like Austria-Hungary, Russia had two plans for the war. One was to be implemented if the Germans attacked Russia first. It involved fighting a defensive war while the French advanced in the west. Almost everyone expected Germany to attack France first so that left the other plan – Plan 19.

Originally developed by General Yuri Danilov, Plan 19 was focused on fighting Germany. Russian forces would ignore Austria-Hungary and concentrate on invading the German province of East Prussia.

Like the Schlieffen Plan, Plan 19 was watered down in the years preceding the war. Danilov’s rivals, who considered Austria-Hungary a serious threat, gained in political power. As a result, the East Prussian invasion force was halved, with the remaining troops moving south to invade the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia. Further forces were held in reserve, ready to join wherever support was needed.

Serbia

Like Belgium, Serbia suffered from being smaller and less powerful than the other nations who were at loggerheads. This dictated its plans.

Serbian generals knew they would face an Austro-Hungarian invasion early in a war. They, therefore, determined to set their forces on the border and hold out there for as long as they could. When that became impossible, they would fall back to the country’s mountainous interior, where the geography would give them an advantage in defense. Having retreated to a defensible area, they, like the Belgians, would wait for their allies to come to their rescue.

Source:

Ian Westwell (2008), World War I