To Europeans, Britons, Canadians, and Americans, stories of World War I often focus on the great battles of the Western Front like the Somme, Ypres, Verdun, Vimy Ridge. But to Australians, New Zealanders, and Turks the first thought that comes to mind is probably Gallipoli.

The Gallipoli Campaign (April 1915-December, 1915) was the British and Allies’ attempt to capture the Dardanelles (the straights leading from Sea of Marmara and Istanbul to the Mediterranean) and eventually march on Istanbul, forcing the surrender of the Ottoman Empire and gaining control of the Black Sea beyond.

It is widely viewed that this campaign was mismanaged and suffered from a lack of commitment to from the start. The most successful operation of the campaign, in fact, was the evacuation.

Gallipoli is the long peninsula that runs across from the North-Western tip of the Asia side of Turkey. Both these sides of the Dardanelles were heavily defended by Ottoman forts and guns. It was Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, who proposed the plan to take Istanbul. The initial attempt was a naval assault.

The British sent a force, comprised of many old and outdated warships, to take the straights, to no avail. The next attempt was by land and so British (including Canadians and Indians), French, Australian, and New Zealand troops were shipped out to Gallipoli.

British ships bombarded the tip of the peninsula, pulverizing Ottoman forts, but losing the element of surprise. The Turkish and Arab troops shored up their defenses with high ground, trenches, machine guns and barbed wire set in the water.

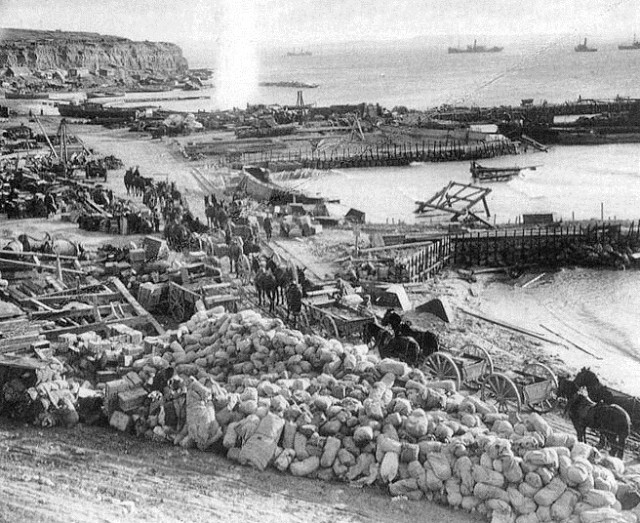

The British and French landed at Cape Helles, the most Southern point, and the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac) landed on what became known as Anzac Cove, a few miles to the North on the Aegean side of Gallipoli, to cut of the Ottomans and meet the other divisions in the middle. But by the end of the day, the Allied forces had hardly made it off the beaches, and 5,000 troops were killed or wounded.

From that day onward, the campaign was a bloody stalemate. The last attempt to break this came in August. The Sari Bair Offensive, which was spearheaded from Anzac Cove, succeeded in pushing several miles inland before the Ottomans finally overcame the weary and few men left by the haphazard assault.

Of the Australian brigades that made it all the way to Chunuk Bair and Hill 60 and the full New Zealand force, which, all combined, began at the full strength of 18,000 men for this final push, only 4,000 lived to see the rest camps Anzac troops were sent to afterward.

The only successes of the push came in taking the beach of Sulva Bay several miles North – though still separated over land by the Ottomans – from Anzac Cove, and the Australian offensive at Lone Pine, on the Southern end of the Cove.

Failures to gain significant ground from Cape Helles, Anzac Cove, and Sulva Bay cost thousands of British, French and Anzac lives. This, combined with the need for more effort in Serbia to fight the Central Empires and disrupt their rail lines to the Ottoman Empire, put a grim light on Gallipoli and on November 22, the evacuation was ordered and the campaign abandoned.

So sure were the commanders of the Allied forces that the campaign was over, that preparations for evacuation began even before the official order was handed down.

Anzac Cove was the biggest worry here. The Ottomans were positioned on high cliffs around most of the area, and very heavy casualties were feared should they notice the withdrawal. This was avoided, however, by the careful and patient plans of Brigadier General Sir Cyril Brudenell Bingham White.

By day, supplies were moved around to appear as though the Anzac troops were preparing for winter. By night, stealthy Indian Mule Corps carried things away to the boats on shore. Troops were told that their fellows being shipped away were going off to rest and would return later, in an effort to maintain secrecy and keep up appearances of a continued and committed front.

Rumors spread around the troops of a withdrawal and by two weeks into December, the plan was officially announced. The full-scale evacuation of troops began on December 15th. This only happened by night, starting with supports and reserves, and then thinning out the trenches. By December 19th, 36,000 troops were evacuated out to sea, and only 10,000 remained.

That night, the remaining troops snuck off. On their way out, many set rifles and explosives on innovative timing devices and planted grenades and mines to both make the Ottomans think they were still there and to harass them with booby traps when they did finally come to inspect the abandoned trenches.

At 4:10 AM on December 20th, Anzac Cove and Sulva Bay were empty, without a single casualty. Though it is thought that the Ottomans were totally deceived by White’s plan, it is entirely possible that Mustafa Kemal, the Turkish General in Gallipoli, was willing to let the Allies slip away, as the campaign caused thousands of casualties among his troops.

In letters home, Anzac troops expressed great remorse at leaving their fallen comrades behind. Though conditions were harsh, food often quite inadequate, and skirmishes full of death, losing their friends in battle and then withdrawing, was a hard blow and difficult to overcome.

The British and French would finally leave Cape Helles in early January 1916.

By the end of the Gallipoli Campaign, the Allies had well over 100,000 casualties, the Ottoman Empire, over 200,000.

The United Kingdom’s National Archives list the death tolls as follows: 28,000 Britons, 10,000 Frenchmen, 7,595 Australians, 2,431 New Zealanders and 1,500 Indians, as well as 66,000 Turks and Arabs. Churchill, as the main advocate for the campaign, was forced to resign from his position in the Cabinet.

The landings on Cape Helles and Anzac Cove became some of the best lessons for the Allies in their preparations for the D-Day landings in World War II.

Video

In 1971, Eric Bogle of Australia wrote the song “And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda,” which tells the story of the Anzac troops at Gallipoli and weighs heavy on the heart.

Here’s a version sung by John McDermott: