In 1917, the world was engulfed in war. For the first time, the economics of industry had been applied to warfare on a huge scale. The result was an unprecedented loss of life across every theatre of conflict. Massed production and massed conscription brought more individual combatants into action than had ever been seen before. The devastating power of mechanised weaponry had changed the nature of war forever.

A line of bayonet-armed infantry marching forward in good order could no longer expect to storm a heavily defended position. Trenches thick with barbed wire and machine gun nests could not be assaulted in the old way, so blankets of shell-fire began to be used as a prelude to an infantry advance.

This was not always effective, and as the war dragged on new ways had to be found to counter the stalemate which trench warfare presented. Ultimately this led to the invention and application of tanks, and the beginning of the development toward the highly mechanised elite armies of today.

Not all the tactics used against trench defences were new. Sappers had been known in warfare since time immemorial. Undermining the walls of cities and castles, and using fire and explosives to do so, had often been practised before. Now the trenches were the siege defences, and the mining technology was scaled up to meet the new demands.

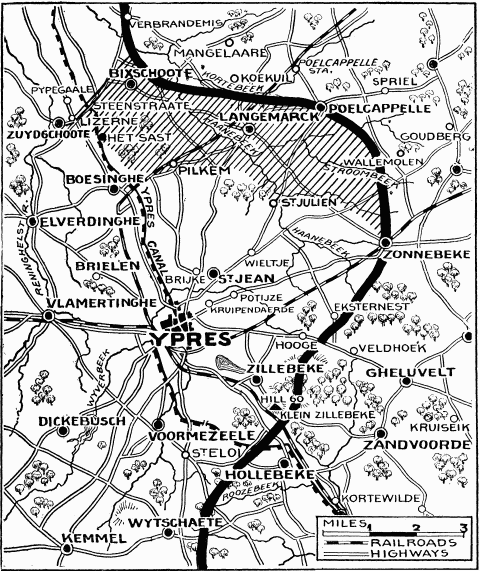

At Messines in Belgium the summer of 1917, the British Second Army opened a long-planned attack. Stretching the length of a high ridge, south of Ypres, the German army held a heavily fortified line of defences against the British. The ridge dominated the landscape, and from it, the Germans controlled a wide sweep of flat country all around. For two years the lines of the entrenched armies had changed very little, and the stalemate continued.

The attack was unleashed just before dawn on the 6th of June, and the opening action represented the culmination of years of work. Since 1915 teams of miners from Britain, Australia, Canada and New Zealand had been tunnelling the area between the opposing lines. Twenty metres below ground level, the teams had excavated tunnels toward the Messines Ridge, then had created galleries off the main tunnels to the right and left.

The Germans were also mining, and though the excavations and counter-excavations came close to one and other – sometimes within a few metres of each other – by the time the offensive was launched the German commanders had no idea that the mining operations had been so successful. The entire ridge, all along the line of the German fortifications, was riddled with tunnels packed with unbelievable amounts of explosive. In total, 454 tonnes of Ammonal and Nitrocellulose gun cotton were packed into the underground chambers.

These explosives had been used to great effect in previous engagements of the first world war, but the sheer quantity used at Messines was unheard of. Ammonal is a cheaper alternative to pure TNT, and gun cotton, or Nitrocellulose, had seen various industrial and military applications since the 1850’s.

Under cover of darkness the British tanks crept into position, the tell-tale noise of their engines disguised by the noise of the planes which strafed the German lines. Gaps had been cut in the British barbed wire, and the attacking troops poured through, massed in the no man’s land facing the ridge.

At three o’clock, all was ready. The British artillery, which had kept up a steady rate of fire all night, was silenced. For a short time, all was quiet. The sky was a very dark blue in the pre-dawn light, and the first birdsong could be heard by the troops who stood at the ready. Just after three, the explosive-packed mine shafts began to detonate.

It was like a force of nature. The men who waited for the assault had seen battle and war for years, but nobody had seen anything like this before. All along the line of the ridge, huge towers of dark orange flames tore upward. The explosions were so loud that many of the men were knocked down by the shock waves. Again and again, all along the dark line of the Messines ridge, massive detonations threw countless tonnes of earth and stone skywards.

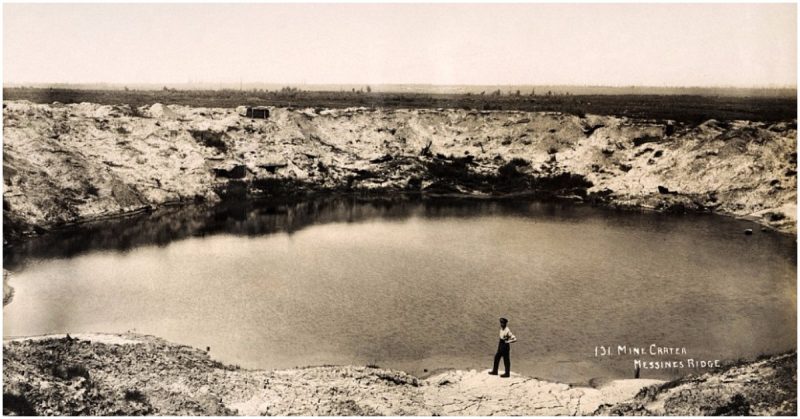

The defenders were taken completely by surprise, and there was nothing they could have done. Artillery, barbed wire and men were blasted into nothingness by the rising flames. It was like something out of a nightmare, the biggest non-nuclear explosions in history. Ten thousand German soldiers were killed when the explosive tunnels were detonated.

There were nineteen explosions in total. Years of work, hundreds of tonnes of explosive – it was all over in a matter of minutes. With the last explosion still ringing in their ears, the artillery crews began to shell what was left of the German positions. They laid down a creeping barrage of shell-fire behind which the attackers began to advance. In the confusion and panic, the German artillery response was weak, chaotic and ineffectual. In a line which was six kilometres long, some eighty thousand troops poured forward under the cover of the barrage.

Everywhere the attackers went, they found the devastation caused by the explosions. The German trenches were caved in, collapsed and broken. The enemy dead were everywhere, and those who had survived could not mount any effective resistance, and surrendered. The advance rolled swiftly across the initial objectives, but behind the ridge German resistance became more determined.

The battle disintegrated into many smaller fights, with isolated pockets of the enemy fighting long and hard to keep pockets of ground. After a day of hard fighting, however, the British Second Army had achieved its objectives and had captured the Messines ridge from the Germans.

Not all of the mines had been detonated in the battle. Several had been left undetonated, being too far away from the German lines to be of any use. In 1955, a lighting strike detonated one of these, killing a cow, though fortunately not causing any human casualties. The huge craters which were created by the explosions on that morning in June 1917 can still be seen today.