The Belgian town of Ypres was the site of the fiercest fighting of the First World War. A series of battles left the town deserted, and the surrounding countryside shattered.

One of those battles saw the first successful use of the horrendous chemical weapons that became an infamous feature of World War One.

The Ypres Salient

Early in the First World War, the opposing forces of Germany and the Allies met outside Ypres. The ridges around the town provided highpoints in the flat plateau of Flanders. After the British held the town and captured some of the ridges, the two sides settled in for a protracted series of fights.

Mines and Counter-Mines

The Second Battle of Ypres was preceded by a brief but dramatic example of military mining.

On March 8, 1915, the British began three tunnels heading beneath the German trenches on Hill 60. The miners encountered problems from the start. First was the soft and sodden ground into which they were digging. Then came the piles of bodies, left from the First Battle of Ypres the previous year. These had to be dug out and reburied.

The Germans were also mining, and there was deadly fighting underground. The British completed their tunnels and placed explosives beneath the German defenses.

On April 17, the British triggered their explosives, smashing the German trenches. Troops quickly took the hill, and after four days of fighting the Germans gave up on retaking it. More than 5,000 men had died, and the main event had not yet started.

Rumours of Gas

Meanwhile, the Germans were preparing to use a new and deadly weapon – poisonous chlorine gas. They had tried it on the Eastern Front, where the bitter cold had stopped the gas dispersing from their shells. It would be the first real test.

Prisoners told the British and French about this impending development. The Allies decided the information was too detailed and concluded it was a lie. They did not believe gas would be used.

The First Gas Attack

On April 22, the Germans opened 5,730 cylinders of chlorine. The gas dispersed into the air and was carried by the wind across the French lines. Most of those encountering it were Algerians, colonial troops serving in the French army.

Chlorine gas causes intense irritation to the skin. If breathed in, it can damage the lungs, causing them to flood, drowning the victim.

Confusion and Resistance

Lungs burning and eyes streaming, the Algerians who could still run away did so. The Germans poured into the gap in the line, seizing the Mauser Ridge.

There was chaos among the Allies. Incorrect information led to poor decisions. The Germans were advancing cautiously, and this provided time to regroup. While French and Belgian forces clung on despite a gas attack, Canadian troops moved up to face the new German lines.

Counter-Attack

The French General Foch responded with a counter-attack. It was disorganized, many of the troops were confused, and the Germans halted most of the attacks.

As so often in the fighting around Ypres, the Canadians proved among the most stalwart soldiers, retaking ground at Kitchener Wood in a midnight bayonetted charge.

The Second Wave: St Julien

The second wave of German attacks came around St Julien on April 24. Again, chlorine gas was unleashed from canisters and allowed to blow across the Allied lines.

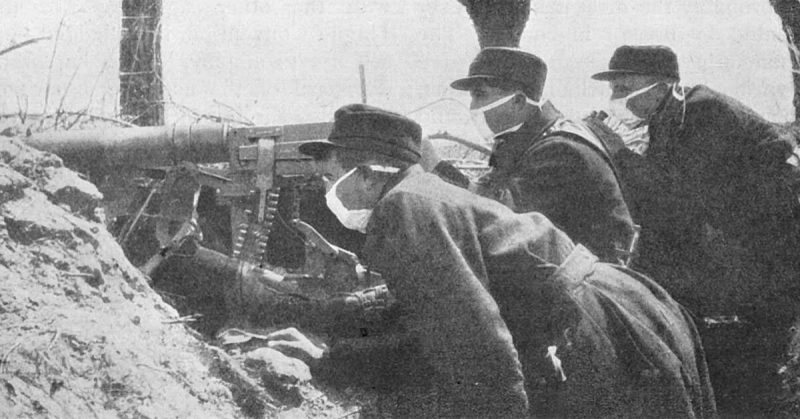

This time, the Canadians bore the brunt of the gas. They had seen what had happened two days before. Recognising that chlorine was being used, they improvised masks out of damp cotton. As a result, more men were still standing when German assault troops descended upon the poisoned Allied lines.

Courage and cotton were not enough. Again, the Allies were pushed back. St Julien fell. Contact was lost with entire units. It was a desperate scramble to ensure the hole in the line was again plugged.

“The Slaughter Was Cruel”: Another Counter-Attack

Once more, the British response was a head-on counter-attack. On April 26, French, Algerian, British, and Indian troops rushed at the German lines. Immediately the Germans opened fire with their machineguns. As Major F. A. Robertson wrote, “The slaughter was cruel. It was men against every machine frightfulness could devise.”

Repeated attacks over the next few days resulted in little success and thousands of troops dead.

Strategic Withdrawal

At last, at the start of May, the Allies recognized they could not retake the line they had once held. Despite protests from Foch, a strategic withdrawal was ordered.

The Allies were not abandoning Ypres. They were conceding ground beyond the town to the Germans, to consolidate their lines and leave troops free for an attack elsewhere on the Western Front.

The Germans Press On

The Germans launched further attacks. Although they were suffering heavy losses, their commanders were set on seizing the Ypres Salient. Gas again preceded the attacks, and on May 5, Hill 60 was retaken, craters and all.

With an orderly withdrawal in mind and gas a known threat, the Allies did not suffer from the same chaos as in the first few days. They slowed the German advance and in places pushed them back.

The final attack came on May 24. Once more using gas to deadly effect, the Germans made one last advance. The Ypres Salient was still in Allied hands, but the Germans held nearly all the high ground.

Broken Ypres

The British suffered over 59,000 casualties, the Germans nearly 35,000. A small but strategically significant amount of territory had been taken. The lines would remain stable for the next two years.

Away from the trenches, Ypres itself was deserted. The continuous threat of shelling had become too much, and the inhabitants had left. At the heart of the corpse-littered fields lay a ghost town.

Source:

Martin Marix Evans (2002), Over the Top: Great Battles of the First World War.

William Weir (2006), 50 Weapons that Changed Warfare.