Erwin Rommel is rightly remembered as one of the most gifted commanders of WWII, but one of his finest achievements took place 20 years before, during WWI.

The Württemberg Gebirgs Battalion

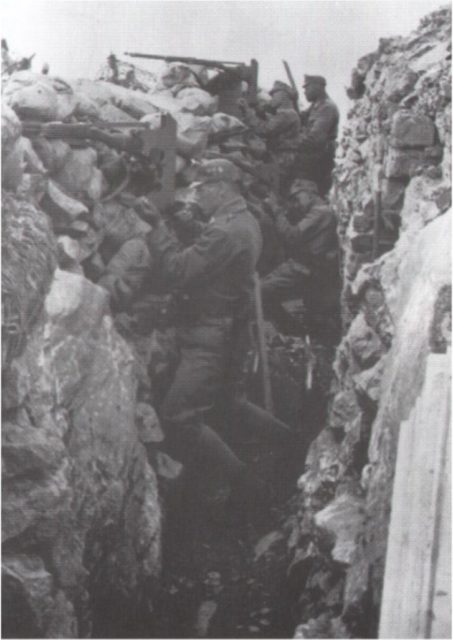

Rommel had already served as an infantry and artillery officer when, in the fall of 1915, he was transferred to a newly created unit. The Württemberg Gebirgs Battalion consisted of six rifle companies supported by an equal number of machine gun platoons. They served in the High Vosges and then Romania before returning to the Western Front.

In 1917, the unit was equipped with new rifles, which were air-cooled and lighter than those they had before. Their machine guns were still the heavy Maxims.

The unit was divided into detachments. Rommel was given command of No. 1 Detachment, made up of three rifle companies and a machine gun company. The reorganization was preparation for service in Italy.

The Italian Front

Since 1915, Germany’s ally Austria-Hungary had been fighting the Italians in the Alps. The Italians were trying to force a route east into their enemies heartland, while the Austro-Hungarians were trying to drive southwest into the plain of Lombardy. Neither side had accomplished much success.

In 1917, Russia’s withdrawal from the war freed German troops. No longer required to fight on the Eastern Front, they were sent south in the hope of finally gaining victory.

Rommel and his detachment were among those sent.

Mountain Targets

A major offensive was scheduled for October 24, 1917. The Alpen Korps, which included Rommel’s detachment, played a critical part in the assault.

The plan involved creating an opening to enable the army to advance down the Isonzo valley onto the plains below the Alps. To attain success, three tough mountain positions on the west side of the Isonzo had to be captured – Monte Stol, Matajeur, and Tolmein.

The Alpen Korps was to take those mountains, then move on to other tactically important positions. If they failed, the entire advance would become stuck in the bottleneck of the Isonzo.

A Swift Advance

Unfortunately for the Germans, Czech and Romanian deserters told the Italians about the impending attack. When the preliminary artillery barrage began at 0200 on October 24, the Italians were already preparing to stop the Germans.

Across the front, German advances were slowed by stiff Italian resistance.

Not so Rommel. Setting off at 0800, he quickly took Italian positions in the area around Tolmein, then advanced to Krn, another peak.

Flanking the Italians

Rommel saw an opportunity to get around the defenses that were holding up his colleagues.

He sent two of his companies up a steep mountain slope in the pouring rain. Unfortunately, the Italians saw them advancing and opened fire.

The quick-thinking Rommel adapted his plan and ordered the two companies to hold where they were. Then he led his remaining troops up a narrow ravine and around the enemy, who surrendered.

The orders Rommel had received emphasized the importance of taking ground. He took the opportunity he had created and continued to advance. Moving at the pace of their slowest troops – the heavily burdened machine-gunners – he led his men in a smooth assault across the mountainsides. Position after position fell to them, including an artillery battery.

Eventually, they were no longer attacking the enemy’s front line. They were in the rear, facing reduced resistance from the surprised Italians.

From Peak to Peak

The Italians had braced themselves to fight against an assault from the Isonzo valley. They were not prepared for a swift advance through the mountains by a small force of riflemen.

By late morning, Rommel was on a ridge facing Monte Hevnik, one of Alpen Korps’ secondary targets. By the end of the day, he had taken Hevnik and the enemy positions between there and Foni.

At dawn the next day, he launched an assault on the Kolovrat ridge. There, his men caught the garrison sleeping and took them all prisoner.

The detachment had captured nearly 1,000 prisoners and a battery of artillery. They were still going.

Trapping the Enemy

Rather than give the enemy time to launch a counter-attack, Rommel kept pressing on.

On a mountain road near Monte Kuk, he cut the telephone lines of an Italian garrison in a nearby village. As groups emerged to investigate, he trapped them in an ambush, capturing the whole force.

Ordered to take Monte Cragonza, Rommel moved on again. He was surprised to run into an Italian trench line but the Italians, thinking themselves surrounded, gave in to his demand that they surrender.

1,000 men and 37 officers were added to his captives.

Viva Germania

Advancing along a ridgeline toward Monte Matajeur, Rommel encountered the 1st Regiment of the Salerno Brigade, who were busy arguing with each other. Seeing him, the Italians rushed over, hoisted him on their shoulders, and called out “Viva Germania!” They had been arguing over whether to lay down their weapons and surrender to the Germans. Rommel’s arrival had settled the debate.

Reaching the peak of Monte Matajeur, Rommel’s small force took the surrender of another 1,200 men. Then he fired a signal flare to show the mountain had been secured.

Medals and Lost Momentum

Rommel’s advance was a huge success. In two and a half days, his detachment incurred 6 killed and 30 wounded. In return, they captured thousands of soldiers, 80 artillery pieces, and a series of tactically significant peaks. For his actions, Rommel was awarded the Pour le Mérite, Germany’s highest award for courage.

The offensive shattered the Italians, but the Germans and Austro-Hungarians failed to follow up on the success. The result was a wasted opportunity, but Rommel could take pride in the part he had played.

Source:

James Lucas (1996), Hitler’s Enforcers: Leaders of the German War Machine 1939-1945