When Paris was the target of German bombers during the First World War, officials immediately began to devise ways to stop future air raids from occurring. Attention was put on anti-aircraft technology, but the enemy simply adapted their tactics. During night raids, pilots used topography to locate targets, and the city wasn’t all that difficult to spot. To combat this, a plan was put in place to create a “faux Paris” – however, construction was only partially completed by the time the conflict ended.

Faux Paris was the brainchild of an electrical engineer

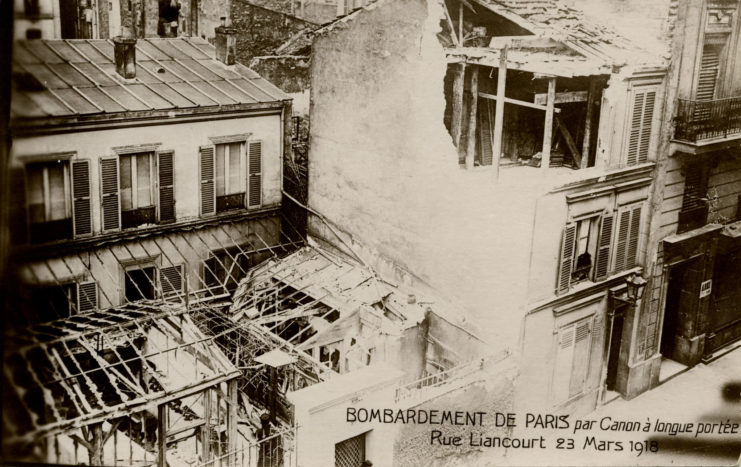

Germany first bombed Paris on August 30, 1914, and the attack impacted the way the City of Lights defended itself. Residents were no longer safe from the war, and while improvements were made to French anti-aircraft technology, German bombers switched to night raids to avoid daytime opposition.

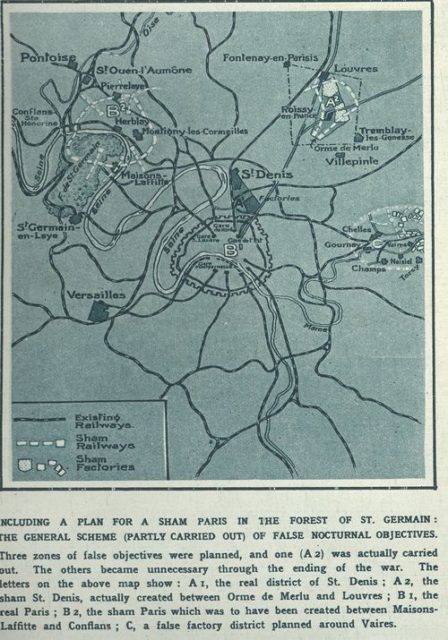

Italian-born electrical engineer Fernand Jacopozzi was living in Paris during the First World War. In 1917, he joined the Défense Contre Avions (DCA), where he came up with a plan to create a faux Paris along the Seine, to trick the German bombers.

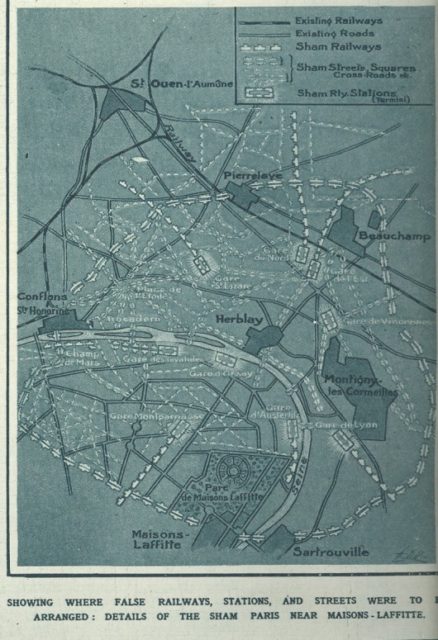

The Seine curves in on itself multiple times. As such, the fake city could be erected along the curve that mirrored where the real Paris is located. This was far enough away that no harm would come to residents. However, the replica would have to be executed with enough accuracy to truly fool the Germans.

“It’s an extraordinary story and one which even Parisians knew very little about,” French historian Professor Jean-Claude Delarue told The Telegraph. “The plan was kept secret for obvious reasons, but it shows how seriously military planners were already taking the new threat of aerial bombardment.”

Zone A: Train station

The first area of faux Paris was named “Zone A.” It consisted of fake train stations surrounded by suburban housing. It would be set to the northeast of the real city. The area itself was surrounded by forests and was far enough away to prevent damage from any bombings.

The fake train was the real marvel of Zone A. Using wood, plastic and other inexpensive materials, it was built along a set of false tracks. Jacopozzi ensured it was outfitted with an intricate lighting system that, from above, actually made the stationary object look like it was moving.

Zone B: Faux Paris

Zone B was intended to be a replica of Paris, located to the northwest. This was to be one of the project’s greatest difficulties, as Jacopozzi wanted to recreate the city’s most iconic architecture, including the Gare du Nord, the Arc de Triomphe and the Champs-Élysées. There isn’t, however, any evidence as to the inclusion of a replica Eiffel Tower.

Another struggle for Jacopozzi was recreating the City of Lights at night. As pilots used landmarks to navigate the area, they would undoubtedly be able to recognize Paris, given its lights display. If the engineer was unable to sufficiently recreate the city’s system, then the faux Paris would fail. Not only that, the expectation was that the real Paris, along with its residents, would cut their lights to cloak the city in darkness and draw attention to the recreation.

Zone C: Industrial district

Zone C would be located directly east of Paris and serve as an industrial area, where massive factories and chimneys would be set up. These structures were to be constructed from sheets of wood, as well as canvases painted in various colors.

In addition to the structures themselves, working furnaces would also be placed within to produce smoke from the chimneys and give the impression that work was going on inside. Using different colored lamps, Jacopozzi created the illusion of fire to truly simulate the look of a working factory.

The faux Paris disappeared

When it came time to build the faux Paris, only work on Zone A truly got underway. The train and its railway were completed and looked remarkably realistic. Small portions of Zones B and C were also done, likely to test their effectiveness before going ahead with the rest of the work.

The plan was cut short when World War I came to an end. As it was no longer necessary to construct or maintain the zones, they were dismantled. “Camouflaged streets, factories, dwelling houses, railways, with stations and trains complete, and in fact a camouflaged capital, was the gigantic task on which French engineers were engaged when the Armistice put an end to military operations,” read a report published by The Globe on October 4, 1920.

More from us: The Battle of Cantigny Forever Changed the US Military

As the entire project itself was a secret, many Parisians were unaware of the construction of a second, faux Paris happening just outside the city limits. Many feel it’s a shame the structures were taken down, as they would have not only served as historic monuments of the war, but also as popular tourist attractions.