The First World War saw incredible technological leaps forward. Though the fighting on the Western Front ground down into a terrible, soul-destroying mess, leaps forward were still being made. From the skies above the battlefield to the hospitals back home, innovations were everywhere.

Fighter Planes

Aerial combat was an entirely new field of warfare. Though the Italians had made limited use of planes to drop bombs on their colonial enemies, aircraft were still a novelty, and before the war inter-plane fighting was unknown.

All of that changed and changed fast. The role of planes in scouting out the enemy meant that they had to be shot down. Soon both sides were carrying weapons into the air then mounting them on the planes. Germany led the way, with the engineer Anthony Fokker building ever better planes and weapons, while pilots such as Oswald Boelcke, Max Immelmann, and Manfred von Richthofen invented ways to fight with them.

In the space of four years, aerial combat went from nothing to a technologically and tactically sophisticated field of battle.

Reconstructive Surgery

Reconstructive surgery, the field of medicine concerned with mending ruined faces and other cosmetic harm, was in its infancy at the start of the Great War. The war changed that. Vast numbers of casualties were caused by flying shrapnel and speeding bullets. At first, rebuilding the appearance of these injured men was a low priority. But as more of them flooded home and the impact on their lives was understood, things changed.

Surgeons such as the New Zealander Captain Harold Delf Gillies pushed for more emphasis on reconstructive surgery. Given ever-growing resources by the British army, Gillies and his team developed entirely new ways to repair and rebuild skin, bone, and cartilage. They transformed everything, from anaesthetic procedures to the use of artists to help recreate faces. A whole field of medicine emerged from the needs of war.

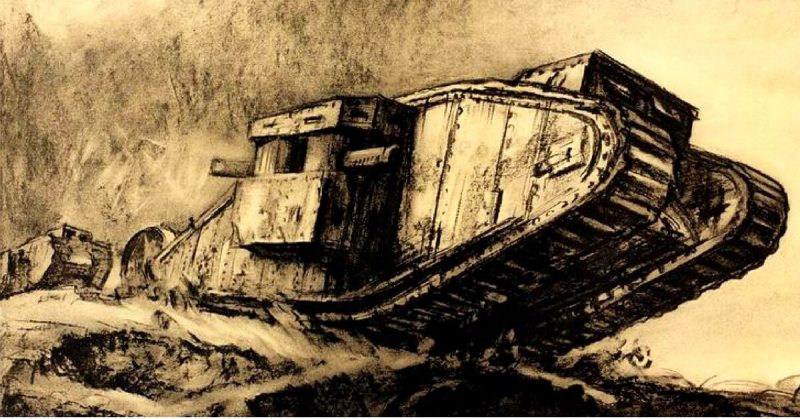

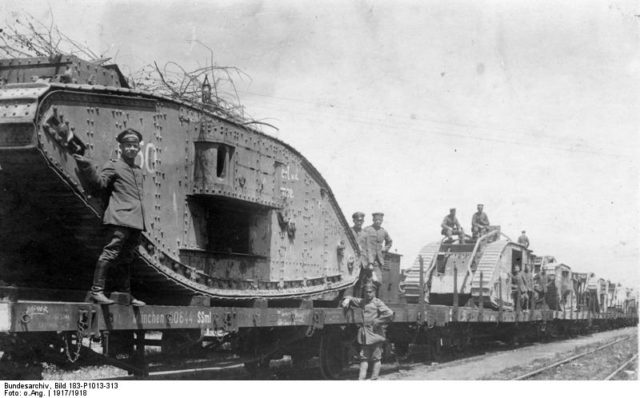

Tanks

Despite the optimistic appraisal of Field Marshal Haig, the First World War saw cavalry fall swiftly into obsolescence. The stopping power of machine guns, artillery, and modern rifles meant that cavalry charges were mown down before they came close to their targets. The superiority of defensive equipment and tactics brought the war to the stalemate for which it is best remembered, with two sides facing each other for months on end across the ruin of No Man’s Land.

In Britain, politicians and inventors set to work on finding a way to break the stalemate and gain an advantage. The solution they found brought together a range of different technologies. Heavy armoured plating from shipyards. The powerful engines of farming machines. The tracked wheel system patented in 1910 by a Californian company under the trade name of “Caterpillar”. When combined, these became an entirely new engine of war – the armoured tank.

Their first use on the 15th of September, 1916, had limited impact. All but two of the vehicles became bogged down and there was no effective plan to coordinate with the infantry. Any advantage they brought went unexploited. But their very presence, previous only foreseen in one of H. G. Wells’s science fiction novels, shook the Germans facing them. All sides accelerated their plans for armoured fighting vehicles. Like planes, they would become a regular feature of later wars.

Aerial Photography

The reason the war in the air developed so fast was the potential it provided for intelligence gathering. If photos could be taken of enemy positions then information could be gleaned from them about what the enemy was doing and what they had planned. And so, like aerial combat, aerial photography moved forward at an incredible pace.

Part of this was down to the innovations of inventors such as John Moore-Brabazon, who led a team creating mounted cameras, new lenses, and better photographic plates for the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). But other innovations were required for this to help. Brabazon’s colleague Victor Laws moved on from invention to training as the first head of the RFC School of Photography, developing a curriculum to cover every aspect of taking good photographs from the air and processing them when time was of the essence.

Systems of interpretation and communication were also created. Technicians learned to interpret what they saw in the photos. They came up with codes for recording and reporting this so that information could be quickly and accurately fed back to the gunners and commanders who would make use of it.

All of these developments would feed into the emergence of aerial mapping after the war, leading to surveys of vast swathes of Australia and America, as well as the discovery and exploitation of oil deposits in the Middle East.

Artillery Tactics

World War One saw all sides deploy artillery on an unprecedented scale. What had once been a small part of the armed forces became the dominant branch of every single armies fighting in Europe. By 1918, twice as many men were in the British Royal Artillery as had been in the entire British army in 1914.

With so many men working in artillery, weapons developed at an amazing rate, becoming larger, more powerful, and more accurate. A series of techniques was developed to make use of their power. With the growing availability of high explosive shells, the barrage was born – a creeping wall of explosions behind which soldiers could advance. On the Eastern Front, the German General Bruchmüller developed the concept of neutralization, using the overwhelming noise and destruction of artillery not to smash the enemy physically but to break their spirit.

Though many of these tactics failed to bring the breakthroughs generals hoped for, neutralization allowed the Germans to make five strong advances in the last months of the war. They came within 40 miles of Paris before economic exhaustion forced them to the negotiating table.