When World War 1 Broke out in 1914, most nations were ill-equipped for a sustained aerial war. The Treaty of Madrid, in 1911, outlined aircraft as purely for reconnaissance and artillery spotting, not weapons platforms. But as the war progressed, these peacetime rules were quickly forgotten, and aerial combat became a possibility.

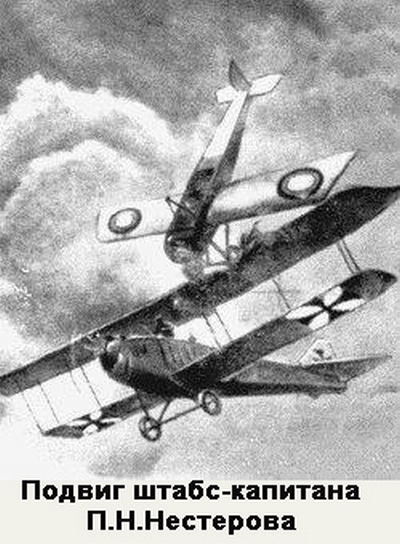

Most planes were relegated to observation and spotting roles. In the rare events that reconnaissance flights would come across each other, the first air to air combat developed. Originally this consisted of pilots throwing rope, grappling hooks, and grenades at one another. One Russian pilot, Pyotr Nesterov, even rammed an Austrian Reconnaissance plane in September of 1914, this has been reported as the first air to air victory of the 1st World War.

As the war progressed pilots, copilots and spotters began carrying small arms. One noted German ace, Wilhelm Frankl, scored his first kill with a Carbine from the back of a plane!

But on October 5th, 1914, French Pilot Louis Quenault opened fire on a German opponent with a forward mounted Hotchkiss M1909 machine gun. This was a turning point in both aviation and military history. But Quenault was piloting a push motor Voisin, which had the engine mounted backwards, and the propeller behind the pilot.

While this provided an excellent firing platform, with nothing obstructing the gun, push craft tended to be slower than their traditional counterparts and quickly proved obsolete.

Early attempts at forward-firing machine guns proved disastrous, the guns firing through the propeller. This, of course, meant that bullets would strike the wooden propellers, shredding them. While some planes took the risk, hoping that even a propellerless glider was a maneuverable craft, most recognized the danger.

One French Pilot, Roland Garros found a solution: deflector plates fitted to the propeller. These steel wedges would send about seven bullets out of 100 scattering, but free of the propeller behind them. On April 1st, 1915 he tried this system out, with immediate success. He downed a German plane and went on to down two more over the next three weeks. But on April 18th, he was shot down, and the Germans discovered the deflectors. Germany asked their chief designer, Anthony Fokker to make an improved version.

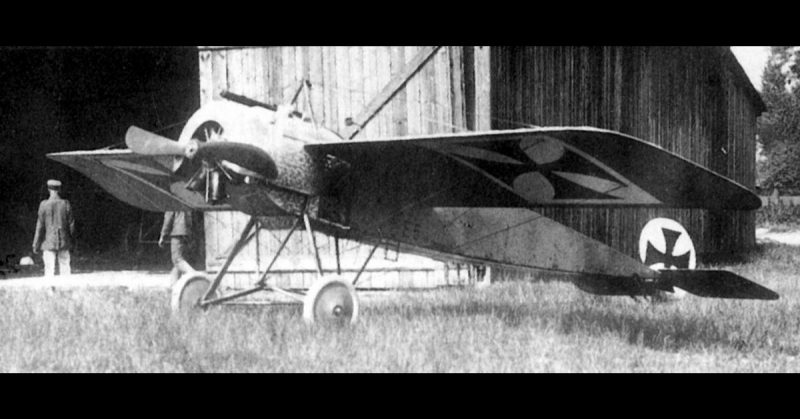

Fokker went far beyond that. He reworked some of the disrupter gear ideas which had been proposed before the war into a combat-ready and mostly reliable system. These gears were synchronized to the firing of the machine gun to the rotation of the propeller, ensuring that bullets never hit it. Fitted to the Maxim MG08, and mounted on the fast and maneuverable Fokker Eindecker (monoplane), the Germans had just found their trump card in the air.

Max Immelman and Oswald Boelcker became the frontmen for this new weapon. Their skill in the air and their love of the lighter, more maneuverable aircraft made them natural fighter pilots. Originally sharing a single plane, taking turns on sorties, they began to rack up kills. The British pilots who faced this new German war machine quickly learned to fear it. In almost every facet, the Fokkers were superior to their British counterparts.

They had forward mounted engines, forward firing machine guns, more maneuverability, and faster speed. What’s more, their machine guns were belt fed, unlike the drum fed Lewis guns which many Allied aircraft used. This allowed them to carry much more ammunition, and not have to reload mid combat, a difficult and often deadly operation. The Fokkers dominated the skies.

As the German victory counts mounted higher and higher throughout the last months of 1915, they began preparations for the battle of Verdun. To prevent enemy reconnaissance planes from finding the massed troops, they used groups of fighters, flying up and down their trench lines, creating an aerial blockade. Allied pilots had learned to fear their German counterparts, and morale dropped as they tried to penetrate the blockade, to little or no avail.

But in war, obsolescence is a “when” not an “if.” And these small, nimble Fokkers were no exception. By the winter of 1915/1916 the French had brought out the Nieuport 11, a fast, light, biplane, with a forward firing Lewis gun, mounted on the top wing. While this was more difficult to aim, clear from a jam, and reload, it was mounted on a far superior airframe. The Nieuports, thanks to their biplane design, were able to easily outmaneuver nearly everything the Germans threw at them.

The French also recognized the necessity for specialized squadrons for these new fighter planes. The Germans still viewed theirs in a defensive role, either protecting reconnaissance missions or preventing enemy reconnaissance from returning home. The British, too, improved their aircraft, using the pusher plane D.H.2.

At first German pilots attacked these new Allied planes without fear. They knew that the intimidating effect of the Fokker’s reputation, would scatter the enemy, and give them easy targets. But early encounters with Nieuports and D.H.2s proved disastrous for the Germans, and their spell was broken. By March 1916, while German aces were still scoring victories in Fokkers, their combat effectiveness had faded.

The final nail in their coffin came in April when one pilot accidentally landed in a British aerodrome. The English captured his aircraft and immediately began testing, and inspecting it. They soon realized it wasn’t nearly as maneuverable or powerful as they had thought, its only real advantage was the synchronizer gear. They soon reverse-engineered this invention and began designing their own forward firing tractor planes.

World War 1 was a war of innovation. It saw the development of the tank, modern infantry tactics, radios, and automobiles. But in the skies, one plane truly revolutionized aerial combat: the Fokker Eindecker.

Its brief career brought fear into the hearts of its opponents, and it was the first fighter for many of the greatest German aces of the war. But its fearful mystique was short-lived, and it was quickly outclassed by French and British fighters. And, thanks to the English reverse-engineering a captured plane, its forward mounted machine guns soon became the standard armament for nearly all aircraft the world over.