Some people get no breaks in life. Sometimes, they have to die before getting the recognition they deserve. Take the case of the Belgian heroine no one had heard of until she was dead.

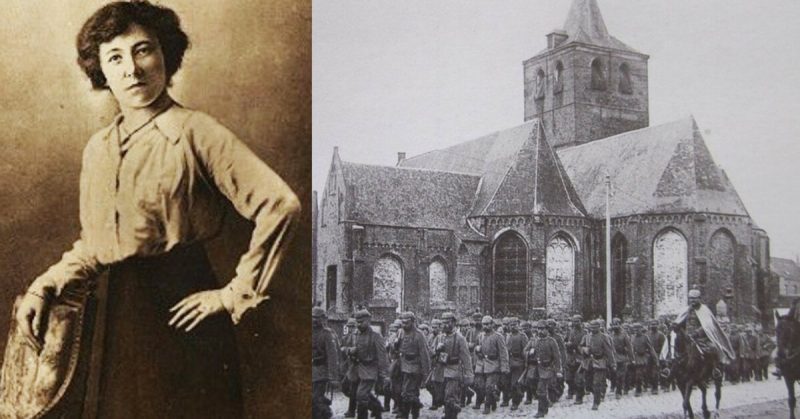

Gabrielle Alina Eugenia Maria Petit was born on February 20, 1893, in Tournai, Belgium to a very poor family. When her mother died when she was nine years old she was sent to an orphanage because her father could not afford to raise her. Petit had wanted to become a teacher, but given her poverty, it simply was not possible.

Upon leaving the orphanage, she worked at several jobs – as a nanny, laundry supervisor, waitress, etc. Estranged from her family, she shunted from one rented bed space to another unil Marie Collet (a neighbor) took her in. Everything changed for her then.

In early 1914, Petit fell in love. His name was Maurice Gobert, a career officer in the Belgian Army with ambition. Gobert promised her not just a future, but a better life. They were engaged, but sadly, on July 28, 1914, WWI broke out. Petit joined the Red Cross.

Gobert went with his regiment to Antwerp. Despite being protected by Belgian, British, and French forces, the city was besieged by the Germans on September 28. By October 10, the Allies had retreated while the Germans marched deeper into the rest of Belgium.

The injured Gobert went into hiding to heal from his war wounds. In May 1915, he made his way to Brussels where Petit hid and cared for him as best she could.

So that Gobert could reunite with his regiment they made their way into neutral Netherlands – not an easy task. The Germans had sealed off the Dutch border with the Wire of Death – a lethal electric fence to prevent saboteurs from entering Belgium and keep a valuable workforce (the Belgians) from leaving.

Petit passed on information about the German Army to the British who asked her to return to Belgium and spy for them. She was reluctant at first but she was patriotic and she hated Germany. After a few weeks of training in London, she made her way back to Belgium sometime in mid-August.

Her duties were simple – observe the border between the Belgian Hainaut region and northern France where the German 6th Army was based.

Becoming bolder, she extended her surveillance work to Brussels. To relay information on troop movements, strength, and weapons back to her superiors in the Netherlands, she depended on reliable couriers – some of whom worked with the Red Cross. She got so good at it the British considered her to be among their most reliable agents in Belgium.

The Le Patriote (The Patriot) was a French newspaper founded in 1884 and was fiercely anti-occupation. The Germans had banned it. In 1915, the paper changed its name to La Libre Belgique (The Free Belgium) and continued publishing in secret. Petit helped to distribute copies of the illegal publication.

Deprived of vital information the Belgians relied on the Mot du Soldat (Word of the Soldier). It was an underground mail service connecting families with Belgium soldiers who fought for the Allies. Petit assisted them and she also helped several other soldiers escape to the Netherlands.

In February 1916 she was betrayed and arrested, together with another female agent. Despite interrogation, she refused to break. According to eyewitness accounts, she took every opportunity to tell the Germans just how much she hated them.

Petit’s trial began on March 2 and ended the following day with a death sentence. However, her execution was delayed because of another woman.

Edith Louisa Cavell was a British Red Cross nurse who was caught helping Allied servicemen escape German-occupied Belgium. Her execution in October 1915 had caused an international outcry and boosted the number of British men who enlisted in the military. The German government had qualms about executing Petit.

She was offered amnesty if she would reveal agents names, but Petit consistently refused.

On April 1, 1916, she was marched to the Tir National execution field in Schaerbeek. Refusing to take the hand of a soldier who tried to steady her or to accept a blindfold, she famously said, “I do not need your assistance. You are going to see that a young Belgian woman knows how to die.”

At age 23 she died for her country but there was no outcry, this time. The Belgians knew nothing about her until May 1919 when the royal family held a state funeral for her and officially declared Petit a national heroine. In her hometown of Tournai, they named a square after her – a permanent home for an unwanted half-orphan.