In November 1914, Turkey entered the First World War on the side of the Central Powers. It was a disappointment for Britain and France, who had hoped to keep the Turks out of the war by diplomatic means.

Few resources could be spared to fight Turkey, as so many men were being poured into the Western Front. Instead, the British and French launched a Naval campaign against the Turks in the Dardanelles. It quickly evolved into one of the most futile expeditions of the war; the Gallipoli campaign.

The Naval Action

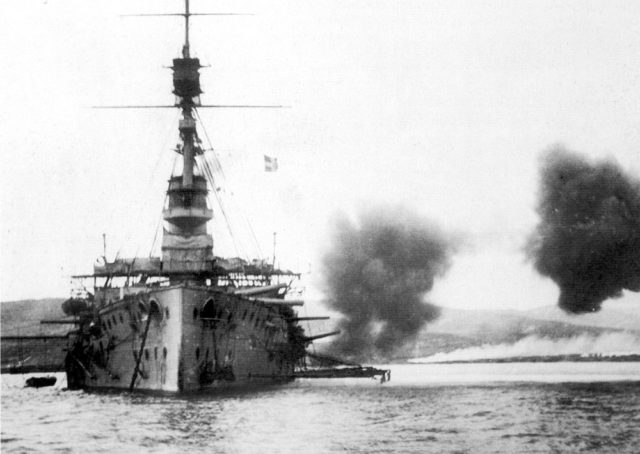

On February 19, 1915, the Allied campaign in the Dardanelles, led by Vice-Admiral Sackville Carden, began in earnest. A week of inaction due to storms followed a day of ineffective bombardment against Turkish shore forts.

Another problem was Naval mines. The civilian crews of British minesweepers feared being shelled from the shore forts as Turkish fire continually disrupted minesweeping operations. Carden, exhausted and frustrated at the failures, stepped down within a month and was replaced by Vice Admiral John de Robeck.

De Robeck sent in battleships to pound the shore forts and make life safe for the minesweepers. The bombardment at first silenced the Turkish guns. On the way out, the French battleship Bouvet hit a mine and went down with 640 men. The British battleships Inflexible and Irresistible, sent to escort the minesweepers, also hit mines. The Ocean, sent to retrieve the Irresistible, hit yet another mine and was lost.

With the Naval action failing, the British changed their plans. General Sir Ian Hamilton was put in charge of a new operation that extended action in the Dardanelles; a ground invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula.

The Landings

On April 25, 1915, the army campaign began. Most of the troops came from Britain, Australia, and New Zealand; the latter two gathered together in the ANZAC Division.

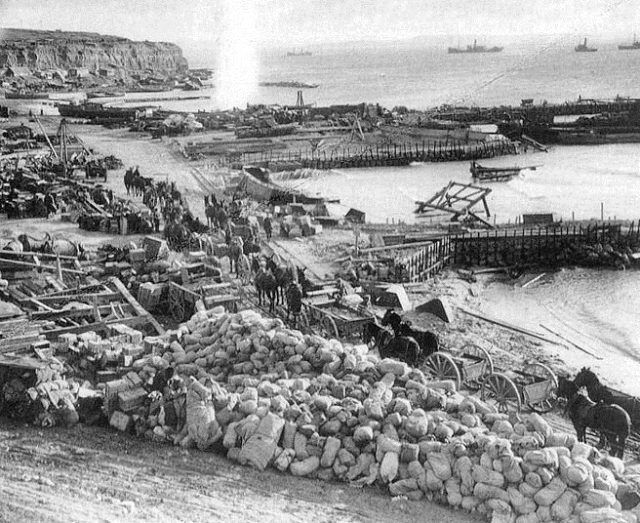

The preparations had been rushed. The operation – a beach landing in the face of heavily entrenched opponents – was unprecedented in modern warfare. The terrain was hostile, with steep cliffs and deep gullies along the coastline. Everything was set for disaster.

British forces were to land at Cape Helles, while the ANZACs were to land further north.

2000 British troops used a primitive landing craft made by converting the collier the River Clyde. The rest of the troops used rowing boats to get ashore. On some beaches, the British faced stiff resistance and were cut down in droves. Elsewhere they met almost no opposition but had no idea what to do next.

Meanwhile, the ANZACs became lost in the pre-dawn darkness and landed on the wrong stretch of coast. Instead of a gradual slope onto the peninsula, they faced steep gullies and tangled scrub. A swift response by the Turkish Mustafa Kemal saw their advance halted.

By the end of the day, the Allied forces were confined to narrow beachheads.

Digging In

Both sides fought hard to overcome each other’s lines, usually with little success. With the addition of French troops, the Allies made some small advances but were still pinned to the coast. Thousands of men died in failed charges by both sides. Soldiers dug deeply into the hillsides for cover.

On May 24, after a month of fighting, a day’s truce allowed both sides to retrieve their dead from between the lines. It was an event that changed the tone of the battle, as men on both sides recognized each other’s humanity. Now their hostility was focused on the people in charge.

Fresh Landings

In early August, convinced that a small commitment of new troops could bring decisive victory, the Allies made a push. This involved advances from the reinforced ANZACs along with new landings by British troops at Suvla Bay.

The ANZAC advance, which included Indian and Gurkha troops, led to some advances at great cost. An attack through a tunnel at Lone Pine resulted in 4000 dead and the award of seven Victoria Crosses. The Australian Light Horse lost 435 out of 450 men. The Turkish lines were pushed back but held intact.

From the hills they had taken, the Allies watched troops under Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Stopford land at Suvla Bay. Sixty-one years old and with no experience of battlefield command, Stopford proved a failure. Rather than advancing quickly to support the ANZACs, he held his men on the beach while they waited for supplies. The Turks were given time to bring in reinforcements. The element of surprise, which had been vital to the Suvla Bay plan, was lost.

Once again, the Allies ended up trapped on the rocky coast.

Evacuation

On October 15, Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Monro took over Allied operations. After a brief inspection, he told British high command they needed to withdraw. Lord Kitchener, the Minister of War, opposed this until he visited Gallipoli in person. Seeing the men freezing in water-logged trenches, trapped by Turkish gunfire, he accepted Monro’s advice.

Lieutenant-General Sir William Birdwood, given responsibility for the evacuation, faced a challenging task. Troops had to be withdrawn without giving the Turks an opportunity to capitalize on an Allied weakness and overrun those who remained.

He began with the ANZACs. On December 13, troops began withdrawing silently by boat under cover of darkness. Guns were rigged to keep firing after their owners had gone, tricking the Turks into thinking the soldiers were still there. By December 18, half the 80,000 ANZAC troops had been removed without the Turks noticing. By the morning of December 21, all the ANZACs had gone.

Withdrawal of the remaining troops began in the New Year. By January 7, Field Marshal Liman von Sanders, the German commanding the Turks, realized what was happening and decided to attack.

19,000 British troops remained to endure the heaviest artillery bombardment of the Gallipoli campaign. At dusk, the Turks charged the remaining British positions and were cut down in a hail of gunfire. Further waves of Turkish troops refused to attack. The German commander’s plan had failed, and the British had bought themselves time.

The last British troops left Gallipoli at 0445 on January 9. The ammunition and stores they could not take with them were destroyed in a massive explosion.

Around 115,000 Allied soldiers were evacuated from Gallipoli. 252,000 had been lost. The campaign ended with smoothness and efficiency, but everything else about it was a disaster.

Source:

Martin Marix Evans (2002), Over the Top: Great Battles of the First World War.