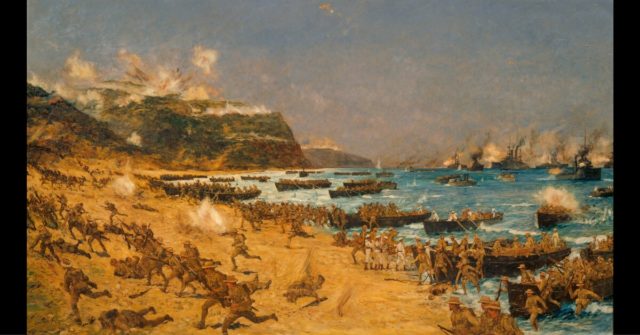

On April 25, 1915, the ground campaign on the Gallipoli Peninsula began. Forces from Australia, Britain, Ceylon, France, India, New Zealand and Senegal landed on the Turkish coastline. The ensuing campaign is remembered as a disastrous failure. What is sometimes overlooked is just how challenging a start it had.

Unexpected, Unprecedented, Unprepared

When the Allies first started action against Turkey, they had not intended to send in armies. With so many ground forces engaged on the Western Front, it was the Navy that went after Gallipoli. A campaign of minesweeping and shore bombardments turned into a fiasco in which four battleships were lost. Suddenly, unexpectedly, a new plan was needed.

At this point, the British decided to send in their Army, including forces from the colonies, with the French providing a small force as they had for the Naval expedition. General Sir Ian Hamilton was given less than two days to plan and prepare before leaving London to undertake this daunting task.

It was not just an unexpected expedition for which those involved were not ready. It was an attack that would require an unprecedented form of engagement.

The Challenge of Gallipoli

For the first time in modern warfare, troops would make a coastal landing straight into the fire of a heavily entrenched enemy. It is a form of war we are now familiar with, particularly from the D-Day and Iwo Jima landings of the Second World War. However, the equipment and techniques that enabled those landings had not yet been developed. The Allies had to work out how to do this.

Gallipoli was an unusually challenging environment for such an attack. Narrow beaches and rugged cliffs made establishing a foothold challenging. The shore was lined with gun emplacements that the Naval campaign had done little to disrupt. Naval mines stood in the way of the landings.

Choosing Landing Sites

The first step was to decide where to land.

One option was the narrow neck of the peninsula at Bulair. Controlling it would have allowed the Allies to control access to the peninsula by land quickly.

The Bulair region was well defended. More Turkish troops could easily be brought in. Also if Bulgaria entered the war, then it could intervene on Turkey’s side there. Even if the narrow stretch of land was taken, Turkish troops could still cross to the Peninsula by sea.

Instead, Hamilton chose two other landing points. British troops would go ashore at Cape Helles, near the tip of the peninsula, to seize the heights at Achi Baba. Meanwhile, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs), featuring troops from various British colonies, supported by forces from France and its African colonies, would land further north. There they would cross the peninsula from the west, taking the east coast and giving the Allies a foothold on the Dardanelles shore.

The Turks Prepare

While the Allies prepared, the Turks were not sitting idle. German Field Marshal Liman von Sanders was in charge of their troops in the area. He oversaw the assignment of defensive forces and the recovery from the damage inflicted by the Naval bombardment. Some were stationed on the Asian coast of the Dardanelles which was not a target for the Allies, although the Turks did not know it. Others were sent to Bulair and Cape Helles, leaving the area in between mostly unguarded.

The Practicalities

Faced with the challenge of how to make the landings, the British officers in charge of the expedition improvised. Most soldiers would be taken ashore in barges towed by pinnaces (small boats propelled by oars or sails). Navy crews would get them as close to land as possible before leaving the troops to row the rest of the way.

A primitive landing craft was made by converting the collier the River Clyde; a boat designed to carry bulky cargoes of coal. Doorways were cut on her side, from which 2000 troops would rush ashore on lighters.

The overall commanders would be based on fighting ships which created a problem once the landings began, as the men in charge were out of contact with their troops.

The Landings at Cape Helles

On April 25, 1915, following a barrage by battleships, the British landed at Cape Helles. At 0612, the River Clyde became beached, stuck too far out for the infantry on board to make it to shore. The ship meant to bridge the gap was swept away, and officers rushed to get the lighters into place and the men onto the beach.

Some of the other boats were also facing problems. The barrage had barely scratched the Turks, who emerged from their trenches to rain bullets down on the beaches. Artillery fire hit British soldiers remaining in the boats. By 0930, the landings on several beaches had stalled.

On other beaches at Cape Helles, the British landed virtually unopposed. Lacking clear orders on what to do next or the initiative with which to act, they too stalled.

By the end of the day, the British had achieved small beachheads around Cape Helles. However, a lack of communication and initiative had cost them the opportunity to press inland. Now the Turks knew where they were and would be ready for the next attack.

The Landings at ANZAC Cove

The ANZACs had an unlucky start. In the pre-dawn darkness, their landing force became lost and landed on the wrong stretch of coast. Instead of a gradual slope onto the peninsula, they faced steep gullies and tangled scrub.

Unsurprisingly, few Turks were there to oppose them on such an inhospitable spot. Soon thousands of troops were ashore and struggled to get inland.

Mustafa Kemal, the Turkish Commander in the area, got word of this and hurriedly sent troops to block their way. In a close-fought battle, the Turks halted the ANZAC advance, retaining the heights that overlooked the landing site.

The ANZACs too were now stuck in a shallow bridgehead. Their advance across the width of the peninsula would not happen.

Beyond the Landings

The Gallipoli landings were a bold attempt to try something new. They turned into a fiasco thanks to poor planning, a lack of initiative, failed navigation, and Kemal’s swift, decisive response. It was a bad start to a bad campaign.

It was also a ground-breaking moment. Development had begun on technology and tactics that would become crucial in later wars, and in particular World War Two. These landings, flawed though they were, were a new type of warfare. The River Clyde would be the first in a whole series of military landing barges.

Source:

Martin Marix Evans (2002), Over the Top: Great Battles of the First World War.