As a South African officer in the British Army of World War One, General Jan Smuts struggled against prejudice as much as he did against the Germans.

The Challenge of War

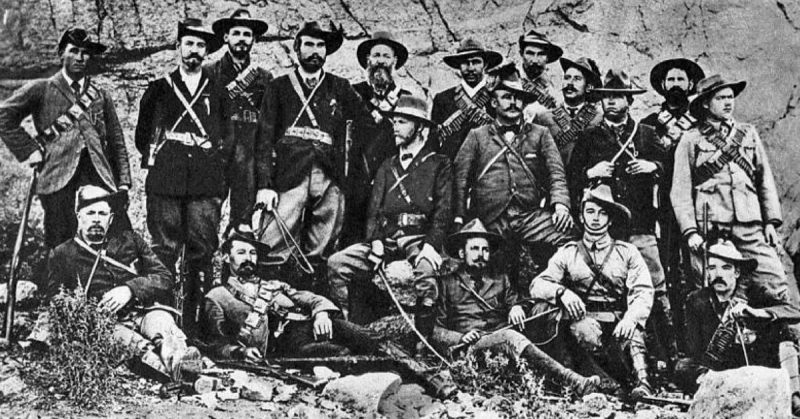

The outbreak of war created a challenging situation for South Africa’s leaders. Many Afrikaners resented their defeat by the British in the Boer Wars. They did not want their country to fight for their colonial masters.

They were living in a British territory adjacent to German South West Africa, and a campaign was expected. Proposals to attack the German colonies led to armed uprisings.

General Jan Smuts found himself in an awkward position. Called upon to suppress opposition, he had to fight his own countrymen before commanding troops in the South West Africa campaign. As a loyal officer, he accepted his duties despite opposing the First World War, which he considered a pointless catastrophe.

The East African Problem

While Smuts was dealing with those political and military challenges, the British were facing embarrassment in East Africa.

East Africa should have been an easy campaign for the British. With far more men and greater resources, they set out to seize territory the Germans had possessed for 30 years.

However, they were faced with stiff opposition led by Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, who fought a creative and determined guerrilla campaign. Assisted by British incompetence in the initial landings at Tanga, Lettow-Vorbeck held up vastly superior forces.

A Leader Robbed of Respect

The British army of the First World War was diverse in race, class, and nationality. Soldiers from all over the empire fought and died not just in the colonies but on the beaches of Gallipoli and in the trenches of the Western Front.

Despite this, snobbery was rife within the army. Most officers came from the British upper class. When Smuts took over an expedition to East Africa, many of them objected to serving under a “colonial” and an “amateur.”

Meanwhile, he faced opposition in the South African press. Nationalist newspapers complained that the expedition was a waste of men and money.

Pushing Back Lettow-Vorbeck

In February 1916, Smuts took over the East African force. He had 45,000 soldiers under his command, many of whom came from South Africa.

Aware of the outcry that high casualties might cause back home, Smuts adopted a strategy of maneuver. His alternative, given the numbers at his disposal, would have been a head-on pursuit of Lettow-Vorbeck, accepting the loss of life in ambushes to bring the vastly outnumbered enemy to battle.

On the surface, it seemed a successful strategy. The Germans were pushed back through the bush and territory was taken. However, it was impossible to bring the wily German commander to a decisive battle.

Guns, Germs, and Rain

As the rainy season kicked in, Smuts’ two lines of advance became bogged down. Roads turned to quagmires, impassable to the horses, mules, and motor vehicles transporting supplies. The men were soaked through and miserable.

In such conditions, illness was inevitable. Dysentery and fever took hold, taking men out of action. Tsetse flies caused the deaths of thousands of horses.

When they could advance, the British and colonial forces were slowed down by the Germans. Small machine-gun detachments, an innovation of Lettow-Vorbeck’s guerrilla tactics, ambushed them before disappearing into the bush.

Despite these setbacks and the prejudice he faced from his own officers, Smuts kept the campaign moving with his confident and dynamic leadership.

He Daily Risked His Life

Some of the heaviest clashes took place along the River Lukigura. Gurkhas, Indians, South Africans, and Britons combined to face German forces. The enemy was better prepared for this sort of warfare, Lettow-Vorbeck having organized and supplied them for a guerrilla war.

Again, Smuts’ leadership came to the fore. He visited the front line daily, to the alarm of his command staff. He risked his life seeing the reality of the fighting.

It worked. Substantial German units were captured along with their weapons.

Dar es Salaam

Throughout the summer of 1916, the British advanced in two columns, one under Smut and the other under Jacob van Deventer. They captured a German supply depot at Morogoro and then the city of Dar es Salaam.

A few weeks after Dar es Salaam, they isolated a German force as it tried to join up with Lettow-Vorbeck. Over 100 German soldiers and 1,500 local troops were captured. These were not huge numbers, but for Lettow-Vorbeck, who had started out with only a few hundred Europeans and a few thousand Africans, it was a lot.

Withdrawal

By late 1916, the South African element of the East African expedition had taken a terrible battering. Disease and combat had whittled away their numbers. It was the sort of carnage that opposition newspapers had been so keen to predict and that could stir further opposition to the war.

The exhausted South Africans were recalled home, as was Smuts. His previously temporary position of lieutenant general was made permanent, in tribute to his achievements.

London and Politics

Early in 1917, Smuts was called to London to join the Imperial War Cabinet. There he again clashed with the British upper crust, becoming involved in political maneuvers between commanders. He turned down command of an expedition to the Middle East as he felt it would not be given the resources it needed.

As a policy maker, Smuts helped to shape the Royal Air Force and Britain’s role in the Middle East in the last year of the war. He still faced prejudice, but his actions in East Africa had proven that he was a capable leader. Those not blinded by snobbery gained much by working with him.

Source:

Geoffrey Regan (1991), The Guinness Book of Military Blunders.

David Rooney (1999), Military Mavericks: Extraordinary Men of Battle.