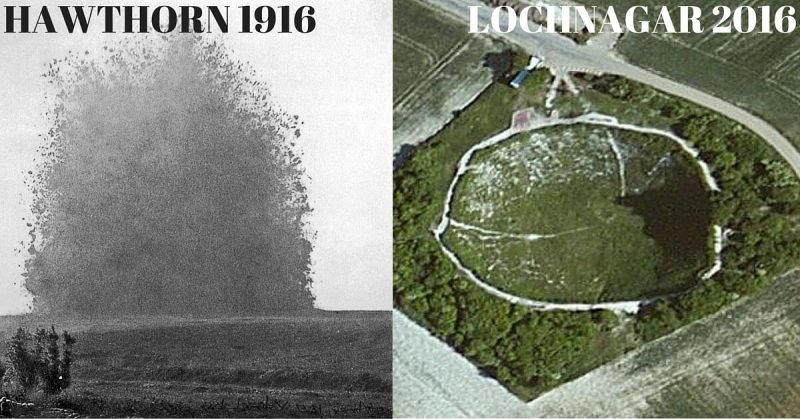

One of the common techniques used in warfare during the First World War was mining. There were various mines planted under trenches, then detonated to send part of the trench, and anyone in it, sky high. Some of these mines were felt as far away as Switzerland. Lochnagar Crater in the Picardie area of France is the most recognizable example of this method.

Mines at the Somme

The Lochnagar mine was dug by the Tunnelling Companies of the Royal Engineers and was detonated at 7.28am on July 1st, 1916. It was just one of eight large, and eleven small, charges that were placed underneath German lines for the first day of the Somme. Both Lochnagar and the nearby Y Sap mines were purposely overcharged to leave big craters with wide rims in the ground.

After the detonation, the main attack began. The crater was occupied by Allied troops as they began to fortify the eastern lip. The advance continued until the German 4th company counter-attacked and British soldiers had to retreat into the crater.

As the day progressed and artillery was fired into Sausage Valley, the Germans used machine-gun fire to take down any British soldier who moved. They also started systematically shelling areas nearby and wounded and lost men sought shelter and refuge within the crater until the German forces began to bomb that as well. The British artillery then also opened fire on the crater, leaving the men stuck inside with nowhere to hide.

The mines in the Somme were detonated as part of a failed attack on the Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt, a German fortification west of the village Beaumont-Hamel. The mine was blown up ten minutes before the start of the general attack, alerting the Germans to its imminence. Despite surface destruction to the trenches, the lifting of the heavy artillery bombardment made it safe for the German soldiers to come out and occupy the front line defenses.

Another mine with 30,000lbs of explosives was laid beneath Hawthorn Ridge for the next attack, which wasn’t until November 13th, 1916.

Remains were found at Lochnagar Crater in October 1998 of British soldier George Nugent of the Tyneside Scottish Northumberland Fusiliers. He was later reburied with military honors in Ovillers Military Cemetary in 2000, 84 years after he died in battle and a memorial cross now sits at the mine site where his body was found.

The site at Lochnagar Crater attracts more than 200,000 visitors every year, and an annual memorial service is held on July 1 to commemorate the detonation of the mine and the Allied and German troops dead, while poppy petals are scattered into the crater.

The tunnellers, when creating the mines, dug up to 100ft below the ground and had to work in complete silence in order to avoid suspicion. They were also tasked with searching for, and stopping any German tunnellers who were doing the same job and tunneling in the opposite direction. When they were confronted with German miners, underground hand-to-hand combat would ensue until there was a winner.

The Mines of Messines

In Belgium near the most active minefield of World War One, there still lies an unexploded 50,000lb bomb sitting under a farm on the Messines Ridge near Ypres.

The mine is sitting 80ft under a barn, and was located by British researchers who were able to do so by using wartime maps.

It was one of many that were set by British miners along the Ypres Salient towards the German trenches on the Messines Ridge. The plan was to plant 25 gigantic mines under the German lines and blow them as part of a major offensive planned for the summer of 1916, but it was postponed until 1917. Work on the mines began 18 months before the offensive actually began and 8,000 meters of the tunnel were constructed.

On June 7th, 1917, 19 of the mines were detonated within half a minute. When the explosions took place more than a million pounds of explosives were backed into the underground chambers along seven miles dug by the miners in an attack that killed 6,000 German troops. The bang was heard as far away as Downing Street in London, buildings within a 30-mile radius shook, and even seismographs in Switzerland were able to register a small earthquake. General Sir Herbert Plumer’s Second Army took the ridge, and the Battle of Messines was considered the most successful local operation of World War One after all initial objectives were taken within just three hours.

However six mines were not used, one 20,000lb mine called Peckham ended up being abandoned due to a tunnel collapse before the operation began, and four on the southern edge ended up not being necessary. The sixth was planted under a ruined farm called La Petite Douve but was discovered by German forces in a counter-mining attack on 24 August 1916 so was never used. One of the four unused mines exploded after 38 years in 1955, believed to have been triggered by a lightening strike.

After the war, La Petite Douve was rebuilt and later renamed. The mine sat almost forgotten for years. Farmer Roger Mahieu told The Telegraph in 2004, “It doesn’t stop me sleeping at night. It’s been there all that time, why should it decide to blow up now?”

The unused Peckham mine is also located underneath a farmhouse on the Messines Ridge.