The First World War saw the birth of aerial combat. Initially used to provide reconnaissance for ground forces, biplanes soon started fighting each other above the trench lines. This was an era of fast paced innovation and glamorous air aces.

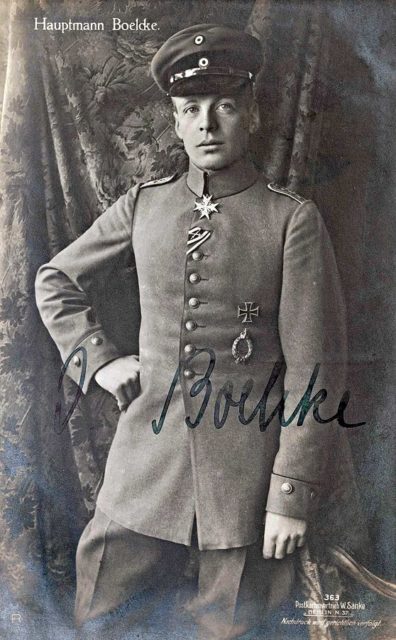

Oswald Boelcke, Father of the German Fighter Force

Oswald Boelcke is regarded by many as the father not only of the German air force, but of fighter combat as we know it. The son of a schoolmaster, he joined the army in 1912, and transferred to the nascent air force in 1914. There he quickly became one of the leading officers, given responsibility for commanding and training other pilots.

Boelcke was a tactical innovator, who paid attention not only to the fast developing technology his pilots were using, but also to that of the enemy. He knew the German planes inside and out, and studied downed Allied planes to learn their limitations.

The tactics Boelcke developed gave his men domination of the skies. They stayed on their own side of the lines to avoid becoming over-stretched, and so that they could coordinate with anti-aircraft guns on the ground. Cloud cover and the glare of the sun were used to hide their approach. Short, intense bursts of firepower were used to bring aircraft down.

Boelcke died in a crash landing during an aerial combat on 28 October 1916. He was only 25 years old, and he had done more to shape aerial warfare than anyone else before or since.

Max Immelmann, the Eagle of Lille

Another of the great early innovators was Boelcke’s wingman, Max Immelmann. Together they developed the tactic of fighter aircraft working in pairs, so that one could focus on navigating while the other paid attention to the skies around them. Able to protect each other’s backs, these pairs of aircraft were deadly against lone flyers or less coordinated groups.

Immelmann created the first notable tactical manoeuvre in air-to-air combat, the Immelmann Turn. This high speed manoeuvre allowed German planes to attack their enemies over and again in a short space of time, inflicting maximum damage and preventing opponents from taking the initiative.

Together, Boelcke and Immelmann were the first pilots awarded the Pour le Mérite, Germany’s highest military honour.

Immelmann died in an aerial fight on 18 June 1916. The Germans could not believe that such a great pilot had been shot down, and his death became a source of controversy. The crew of a British plane were awarded medals for killing him, while some in Germany claimed it had been friendly anti-aircraft fire, and others blamed a mechanical failure.

Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron

The most famous pilot in history, Richthofen was a student of Boelcke, and took his place as the leading German innovator following Boelcke’s death. His nickname comes from the colour of his plane – under him, German pilots painted their planes in bright colours, earning his formation the nickname the Flying Circus.

Richthofen was the single most deadly ace of the war, shooting down 80 opponents and leading the German pilots in their triumph of “Bloody April” 1917.

Like his mentor, Richthofen died in combat. Hit during fighting on 21 April 1918, he was conscious enough to bring his plane down to land, but by the time anyone reached him he was dead. The cause of his death was also disputed, though this time it was between allied fliers and troops who had shot at the plane from the ground.

Lanoe Hawker

One of Britain’s most innovative pilots in the early war, Lanoe Hawker was driven by a fascination with flight. Learning to fly at his own expense in his early 20s, he joined the army in 1913 and transferred to the Royal Flying Corps in 1914.

Hawker was a great technical innovator. He worked with others to develop new gun mountings, ammunition feeds, and other adaptations of the aircraft, as the British raced to keep up with their opponents. His ideas extended to the targets the flyers practiced shooting at and the boots they flew in.

A skilled pilot, Hawker was the first British flyer to become a flying ace, a title earned by shooting down five or more enemy planes. For this he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Hawker died on 23 November 1916, shot down by the Red Baron. Richthofen retrieved the Lewis gun from the wreckage of Hawker’s plane, and hung it in his quarters as a trophy of war.

René Fonck

The most successful allied air ace of the conflict, French pilot Colonel René Fonck began the war as a combat engineer, digging trenches and building bridges. He had always been fascinated by flight, but was initially rejected when he asked to transfer to the air service, and had to wait until February 1915 before beginning his training.

Fonck quickly earned the respect of his peers for his skill in the air. Bringing mathematical precision and engineering knowledge to the air, he understood the planes and how they worked like few others. Patient, careful and calculating, he preferred merciless ambushes to dogfights, and used very little ammunition due to his precise deflection shooting.

Socially withdrawn and prone to self-promotion, Fonck was never popular with other pilots or the public. He survived the war with a total of 75 confirmed kills and many more claimed, second only to the Red Baron.

Billy Bishop

Canadian ace Billy Bishop didn’t even become a pilot until halfway through the war. Joining the Royal Flying Corp in 1915, he spent a year as a spotter for other pilots before being trained to sit behind the controls.

A fighter since childhood, Bishop led from the front, flying all-out on the attack. He survived being shot down in no-man’s-land, achieved 72 kills, and was awarded the Victoria Cross for his achievements. A reminder of how important Commonwealth countries were to the British war effort, he survived the war and went on to become an Air Marshall.