Success in war is as much about avoiding death as about inflicting it. In modern warfare, doctors, nurses and field medics are as vital to an army as the men whose lives they save. In World War One, as new advances in weaponry inflicted incredible destruction upon fighting men, incredible work was also being done in saving their lives.

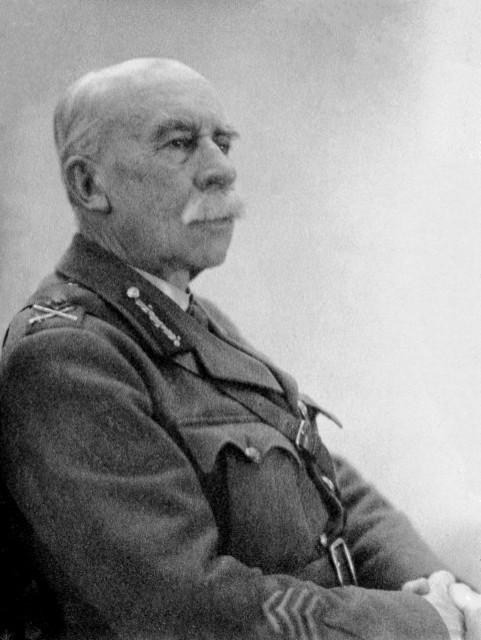

Lieutenant General Sir William Boog Leishman

Born in Glasgow in 1865, Leishman’s career had always combined medicine and the armed forces. After graduating from the University of Glasgow he emlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps, where he researched tropical diseases while stationed in colonial India. Back in Britain, he joined the Royal Army Medical College where he became a Professor of Pathology.

Leishman was most noted for his work in studying disease and was the president of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene from 1911 to 1912. During his work, he developed new typhoid fever inoculations.

Typhoid had been a real menace to the British Army during previous wars, and Leishman’s work saved an estimated 130,000 lives as well as preventing 900,000 men being invalidated out of the army.

On his death in 1926, his Royal Society obituary stated that “For this achievement, Leishman must be accounted to have been one of our most successful generals in the Great War.”

Sir Arthur Sloggett

All the medical supplies in the Empire would have done no good without an effective system to get them into place. The man responsible for ensuring that treatment was well organised was Sir Arthur Sloggett.

Sloggett was another career army medic, and Director General of Army Medical Services when the war began. Outgoing and cheerful, he got on well with the commanders running the war, helping to ensure smooth cooperation. His was a role of management and leadership, which could have been conducted from London, but when he saw the chaotic nature of initial efforts he relocated to France. The part of his job based at the War Office was passed to Sir Alfred Keogh while Sloggett reorganised medical care on the ground for millions of troops.

Sloggett and Keogh together quietly transformed Britain’s military medical care. They increased supplies of antiseptic and anaesthetic and oversaw the provision of field dressings to all soldiers, allowing swift emergency treatment and better care down the line.

Sir Anthony Bowlby

Recognising the limits of their knowledge, the army consulted with senior surgeons on how to better treat the injured. Sir Anthony Bowlby was the most important of these surgeons. Though he had not served in the army, he had been a volunteer surgeon for the British forces during the Boer War, and so understood the beast with which they were grappling.

Bowlby pushed hard to modernise ways of working. In particular, he fought against the practice of bringing men far from the front before treating them. The sooner they were treated the more likely they were to survive, and that meant moving medical services closer to the battle zones.

Another of the changes Bowlby saw took place in the Casualty Clearing Stations (CCS), bases that effectively acted as miniature hospitals a few miles behind the lines. He pushed them into specialising in the most important treatments for the wounded, including head injuries and abdominal wounds. CCS took on an increasingly important role, providing more and more medical services including surgery, to ensure that men were treated as quickly as possible.

Captain Harold Delf Gillies

A New Zealander educated as much in Britain as in his homeland, Gillies was one of the great innovators of the British medical war effort, and of the field of plastic surgery.

Having worked in London as an ear, nose and throat surgeon, Gillies was familiar with the delicate operations that could take place around the head and face, and the scars they could leave. When the war broke out, the 32-year-old spent several months as a Red Cross volunteer in France and Belgium, being exposed to the horrors of war. While on the continent he was also exposed to the work of Europe’s most famous plastic surgeon, Hippolyte Morestin. The operation Gillies saw Morestin conduct, removing a face cancer and repairing the wound, was a revelation to him.

Back in Britain, Gillies approached Bowlby. Gillies had become a passionate advocate for reconstructive surgery and believed that the war made it doubly important. The huge number of head wounds meant that many men would be disfigured for life. Gillies argued that the army should have its own unit to deal with reconstructing the faces of the injured. Bowlby was persuaded, and he, in turn, persuaded Keogh. In January 1916, Captain Gillies was sent to the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot to start work.

What followed transformed the lives of thousands of men, as well as the techniques of reconstructive surgery. Gillies and his team had no textbooks to guide them and so developed techniques of their own as they rebuilt bone, skin and cartilage. New ways of replacing skin were developed. New challenges in anaesthetics were overcome. Bone grafting techniques were invented to rebuild noses and jaws. Artists were brought in to help them recreate features and restore faces to what they had once been.

By the Battle of the Somme, Gillies had been given an extra 200 beds in another hospital, but in the face of the appalling casualties from that battle, it was not enough. He worked around the clock seven days a week, rebuilding not just men’s bodies, but their morale. Faces are so important to human identity that facial damage could crush a man’s spirits. Calm, encouraging and cheerful, Gillies helped men to believe that they could survive what they had undergone. By the end of the war, doctors were coming from around the world to learn from him.

Sources:

Taylor Downing (2014), Secret Warriors: Key Scientists, Code-breakers and Propagandists of the Great War.