The Keeling Islands are little more than overgrown coral reefs, but in 1914 they saw the beginning of one the most epic adventure stories of the First World War.

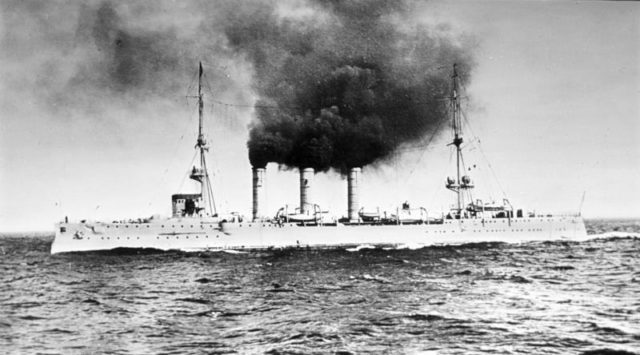

SMS Emden, an Imperial German cruiser raiding British commerce, arrived off of the Keelings early in the morning of November 9th, 1914.She was hoping to destroy the telegraph cables which ran through Direction Island, in the Keeling atoll.

These cables were used to communicate between the British Colonies and military. It was hoped that their destruction could cut off the British fleet from the rest of the Empire. Kapitan Leutnant Hellmuth Von Mücke, the Emden’s Executive Officer, was tasked with leading their destruction.

Hellmuth Von Mücke was born in Zwickau, Germany in 1881. He first joined the Imperial German Navy as a cadet in 1899 and had a successful career on torpedo boats. By 1914 he was the Executive Officer of the Light Cruiser Emden and was about to embark on a daring adventure.

Von Mücke was in charge of a landing party sent from the SMS Emden to destroy the British underseas cables used for communications throughout their empire. His 50-man landing party arrived on Direction Island shortly after 06:00 AM on the 9th of November 1914. Emden was anchored nearby, awaiting a coaling ship.

The landing party quickly rounded up the local officials on the island and explained their new situation. Von Mücke gave his word that none of the local men would be harmed, so long as they did not get in the way of the German troops. Their targets were the radios, telegraph equipment, and cables, not the people.

The landing party set about destroying every piece of equipment they could find, burning much of it in a large fire. They cut the cables and were preparing to return to the Emden when everything went wrong. The Emden sounded her siren, signaling those on shore to return as quickly as possible. The landing party headed back to their mother ship in a small steam launch, and two rowboats. But the Emden had weighed anchor and began steaming away. The landing party was marooned.

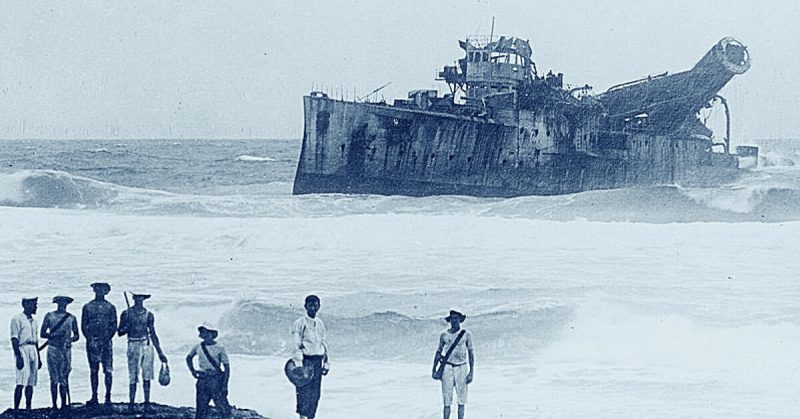

It soon became clear that the Emden was under attack from the Australian Cruiser HMAS Sydney. Outgunned, the Emden put up a fight, but soon steamed out of view of the island. Von Mucke knew that other British ships would soon come to check on the condition of the communications station. His men had to escape, and quickly.

Again they rounded up the locals and told them that the schooner Ayesha, an old freight hauler sitting at anchor in the harbor, was now Imperial German Property. The locals encouraged Von Mücke not to take her, for his own sake. She was old, poorly maintained, and had a rotten bottom. But von Mücke continued and began to provision her. The locals even joined in, having been treated well by these strange Germans they felt little enmity towards them. They gave them newspapers, clothes, blankets, and what food they could spare.

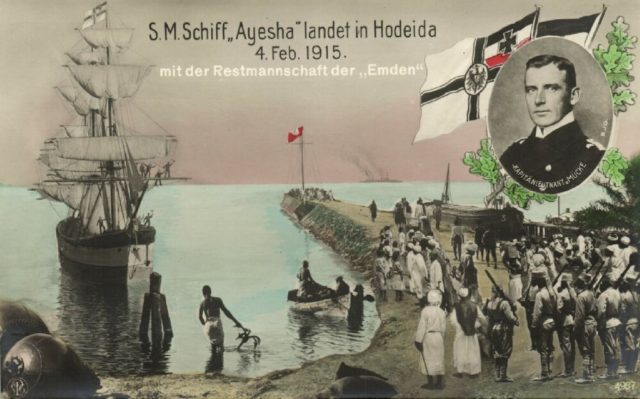

Just before nightfall the schooner, now SMS (Seiner Majestät Schiff, German for His Majesty’s Ship) Ayesha, sailed out heading for Padang, a neutral Dutch port. They had to skirt around dangerous reefs and shoals, survive massive storms, and even dodge detection from the enemy. One torpedo destroyer found them, but rather than attacking, the officers and crew merely watched this small strange sailing vessel. Passing only a matter of yards off Ayesha, the warship’s crew must have been completely baffled by this old schooner manned by a ragtag group of German seamen.

They finally made it to Padang on November 25th but were only given 24 hours to refit. To make matters worse, the Dutch were refusing to allow clothing or charts to be sent on board. The crew had cobbled together a chart made from various almanacs, stories, and guess work, but it was not accurate, or safe to use. Despite the danger, von Mücke, and his crew were forced to set sail again, heading south and hoping to meet with a German steamer.

After two weeks of almost blind sailing, they finally stumbled on the steamer Choising, a German merchant sailing from Padang. Von Mücke arranged for his men to transfer onboard, and for him to take command. After offloading her supplies, they had to scuttle the Ayesha. But this proved harder than expected, and the little schooner kept following the Choising as if refusing to give up. Finally, the Choising came to a stop, and the whole crew watched as the little schooner slowly sank.

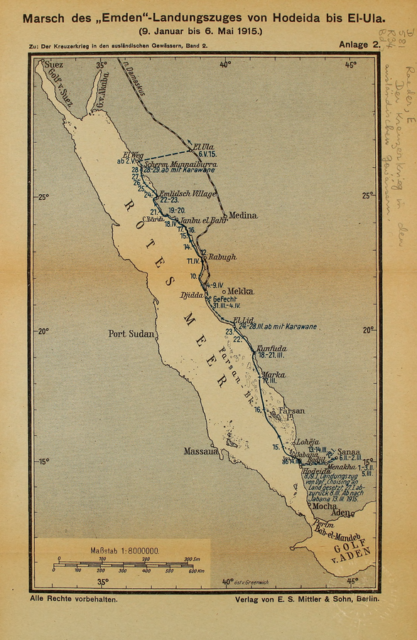

Disguising themselves as the Shenir, a British ship sold to an Italian firm in Genoa, they steamed for Arabia. They had just learned that the Turks had joined the war as an ally of Germany and knew that their best chance for survival was in friendly territory. They avoided shipping lanes, taking a circuitous route around the Indian Ocean, and approached Hodeida, Yemen, early in January 1915. But spotting a French cruiser off the shore, the landing party left the Choising in long boats, and rowed and sailed towards the shore.

Finally making it to Hodeida itself, they were then faced with how to return to Germany. At first, a land route was attempted but then abandoned. Instead, the men took two small dhows – Arab sailing vessels – of about 40 feet each. Again they snuck forward until they reached Al Qunfidah in late March of 1915. From here they skirted the British blockade in the Red Sea, and proceeded by land on camels and donkeys to Djedda, surviving a three-day attack by 300 Bedouins along the way. It was later discovered that these Bedouins were supported by the British, as they carried British rifles. Finally, on the 9th of April they left Djedda, again returning to the sea in dhows. Sailing northwest they reached El Wegh, southwest of the rail station at Al-Ula. On May 2nd, they set out by camel again, traveling overland through the sparse and open terrain.

By this time news of their amazing journey had reached the world. By the time they reached Al Ula, there was already a train waiting for them, accompanied by two German diplomats and a Turkish military detachment. From here their journey was finally easy. They rode the train north through the Middle East to Anatolia. Along the way, they finally received mail, a constant stream of food and drink, and even Iron Crosses, awarded to the entire landing party for their bravery and skill. Over their ten month journey from the south Pacific to Germany, they lost ten men, but had gained the respect of the German nation, and the world alike.