The horse was the mainstay of battle logistics in World War One, pulling munitions and armaments, transporting the sick and wounded.

But they were also casualties in the war that saw the end of their extensive use in modern warfare. The rotting corpses of fallen horses were a common sight on the battlefields of the Somme.

The area that became no-mans-land between the trenches became a hellish region, blasted by shelling, strewn with barbed wire and booby traps, the final resting place of thousands of infantrymen from both sides.

It was impossible to cross, and trench warfare later became synonymous with stalemate.

During this period, finding out what your enemy was doing became a key activity as both sides tried to push forward and take ground by any means.

The Allies and the Germans both needed intelligence in order to gain any sort of advantage and reverted to very creative means in order to get it.

The French had already been experimenting with papier mâché making realistic heads which they propped above the edge of the trenches in the winter of 1915, in order to draw out sniper fire.

Letting the sniper hit these fake infantrymen meant that the location of the shooter could be established and then accurately targeted.

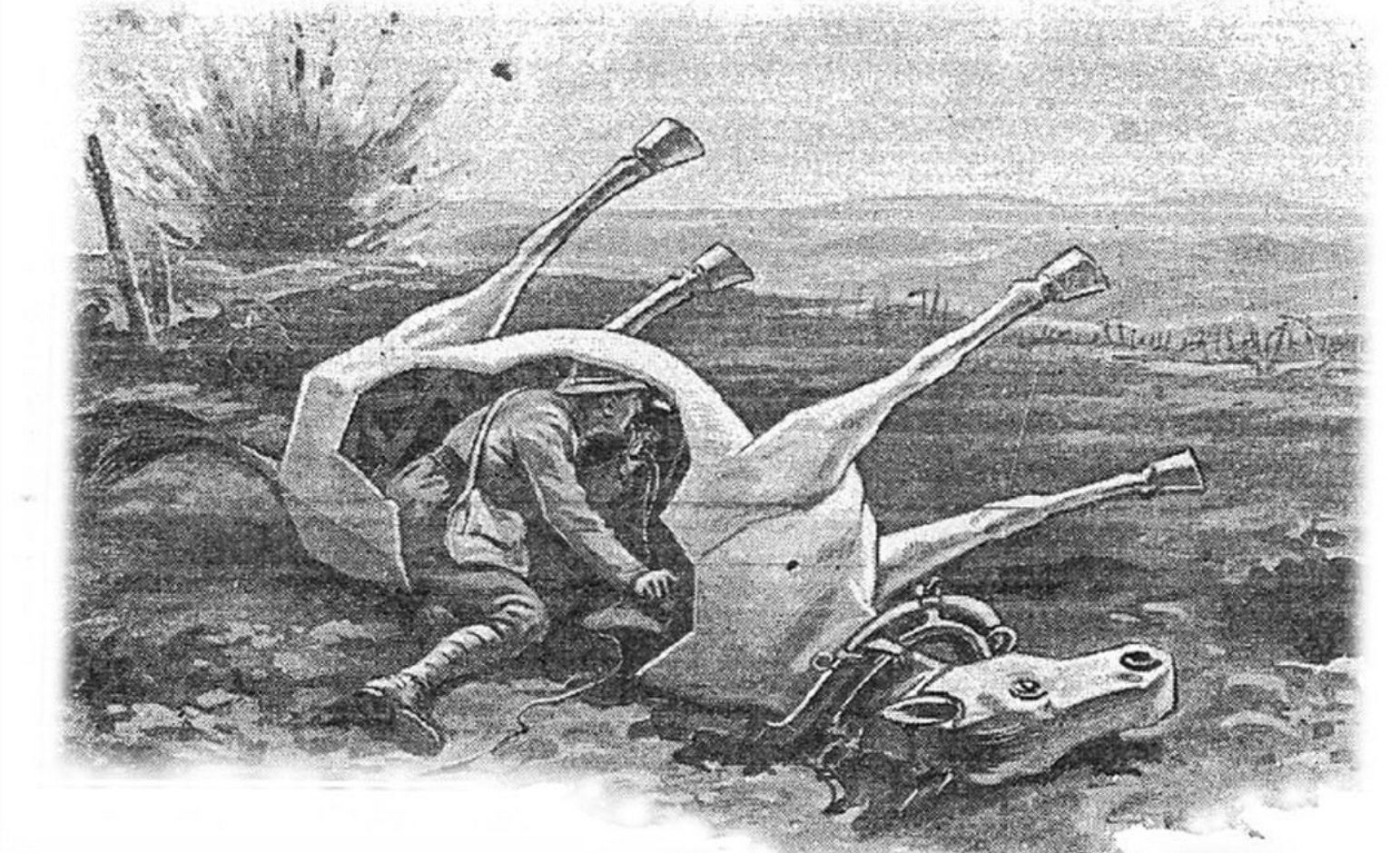

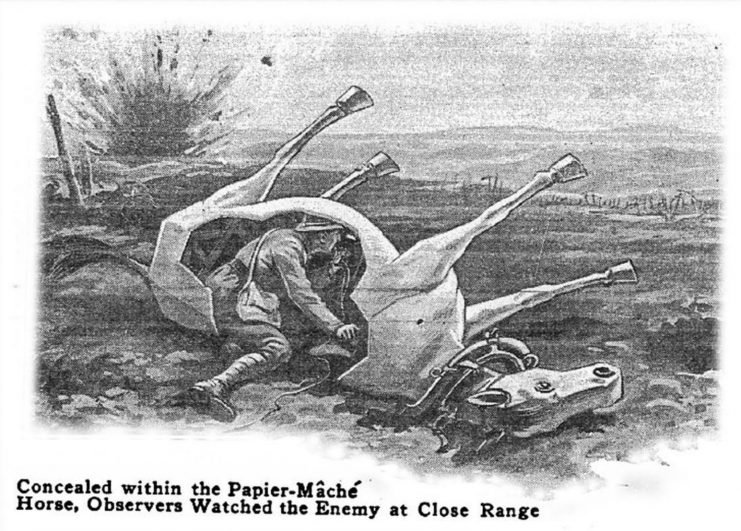

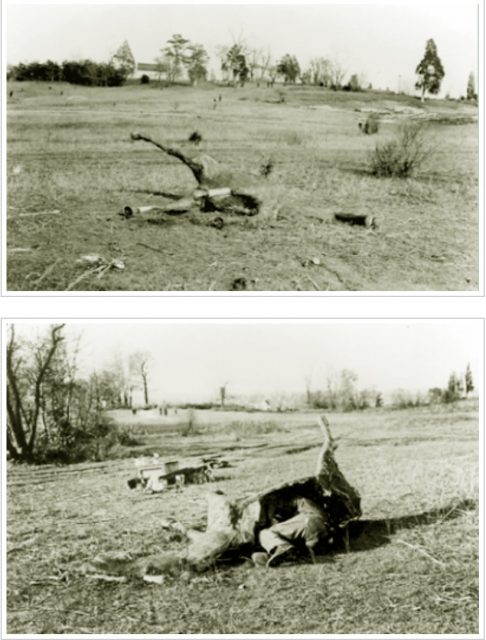

But their use of papier mâché did not end there. Emboldened by their success with mannequins the French changed up a gear and created an entire phoney horse carcass.

The idea was inspired by observing that the carcasses of horses, some quite close to enemy trenches, went largely ignored by the Germans.

One night a group of French soldiers snuck up close to the enemy line and dragged away the dead horse and replaced it with the papier mâché replica.

A sniper crawled inside while his comrades reeled out a telephone wire from the horse to the trenches so the sniper could report any observations of enemy troop movements.

The French got away with this subterfuge for three days before the Germans spotted the sniper climbing out of the phoney pony.

They wasted no time in obliterating the decoy, but the first attempt was considered such a success it went on to be used again on a number of occasions.

Such cunning with regard to camouflage was not the sole preserve of the French military, the German army for their part were also able to come up with remarkably durable spyware.

In Belgium there was an array of blackened and burned out stumps called Oosttaverne wood smack in the middle of no-man’s land, near Messines.

In 1917 the German military built a twenty-five-foot-tall tree stump out of steel pipe, painting it to resemble burned bark to merge with the remaining tree trunks.

It was a tight space but had just enough room to conceal a sniper, who would also be able to report back troop movements he had seen from his forward position.

Using diversionary fire to distract the allies the Germans cut down an existing tree and replaced it with the steel replica.

The fake tree was brazenly set up overnight in a huge logistic effort amongst the remains of the wood.

It stayed in operation until the Germans had to retreat following the Battle of Messines, when the British tunnelled under the German lines and destroyed their trenches from below.

However, the tree was so successful that the Allies had no idea for months that their movements were being spied on from such close quarters.

Indeed, the British had been established in their forward positions, alongside the fake tree for several months before it was finally discovered. After the war, the tree was put on display at the Australian War Memorial.

Have You Heard of The Special Forces Ghost Car That Operated in Bosnia

The work of the World War One war horses has been commemorated in many memorials, books, films and stage shows.