The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 had an unusual effect in Ireland. In a place where there had already been conflict and hatred, the declaration of a European war in August that year actually brought a modicum of peace, at least for a while, to the debate between those who pressed for an independent nation and those who wished to remain part of the United Kingdom. In the north-east of the country, the majority Protestant descendants of 17th century English and Scottish settlers had been campaigning voraciously against the seemingly inevitable adoption of an autonomous Irish parliament in Dublin for more than thirty years, and their counterparts in the Nationalist movement were just as determined to see it brought in.

In the northwest and south of the country, the apocalyptic famines of the 19th century were still within living memory. In the time between the outbreak of the Great Famine in 1845 and the Battle of the Somme in 1916, fully a half of the entire Irish population had either died or left the country to avoid starvation and profound poverty, nearly all of them leaving the western half of the island to go to Britain, its colonies, or the United States.

On the eastern shore, Dublin in the 1910s was the still the same Edwardian city that James Joyce immortalised in his masterpiece “Ulysses,” a modern, stream of consciousness retelling of Homer’s Odyssey. It was a semi-industrialised metropolis, where the few factories mainly centred on processing the foodstuffs that the rich farmlands around produced. The Guinness Brewery was the city’s largest employer. The north of Ireland, by contrast, was much more industrialised, with the city of Belfast famously building the Titanic in its vast Harland and Wolff shipyards.

Prior to 1914, both of these regions’ conflicting wishes for the government of Ireland had almost led to outright conflict, with a northern Ulster Volunteer Force formed in 1912 as a paramilitary body to oppose “Home Rule” should it be introduced. This was answered with the creation of the southern based “Irish Volunteers” within a year to oppose them in turn. With British officers preferring mutiny to disarming the quarrelling groups, Ireland appeared on the brink of civil war in 1914.

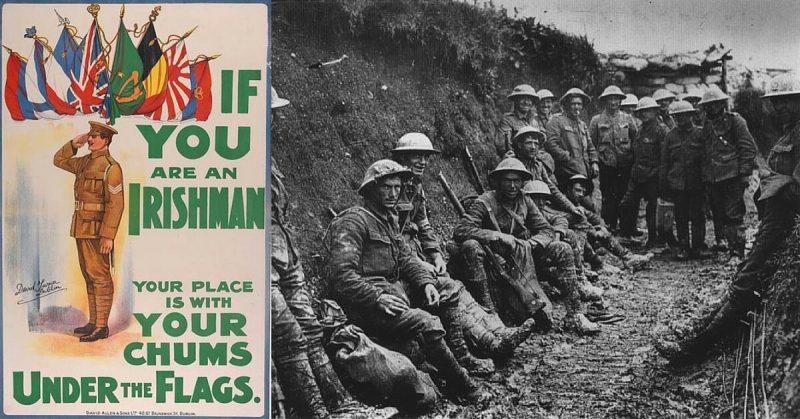

The German invasion of Belgium in August that year provided something of a welcome relief then, at least for the British and Irish leaders. The commanders of the Irish Volunteers promised their ranks that going to the aid of a small, Catholic country like Belgium in the name of the United Kingdom would ensure that Home Rule would be introduced in return. On the other hand, the Ulster Volunteer Force immediately offered its services to the Crown to prove its loyalty. With such ironically divergent ends, Ireland went to war against the Central Powers in 1914.

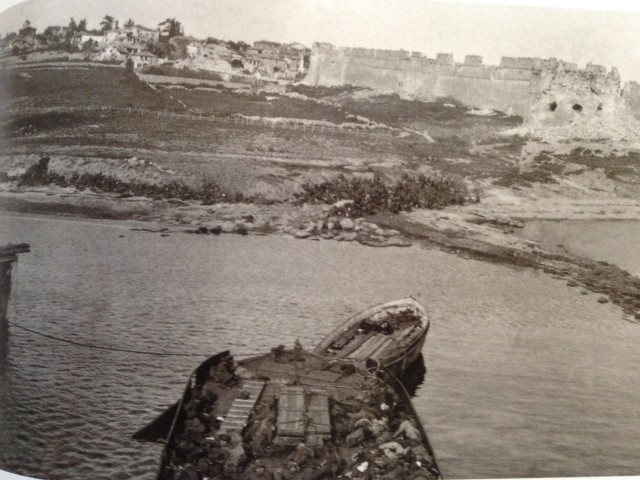

By the time of the Battle of the Somme two years later, the Irish were no strangers to the carnage that involvement in what was becoming known as the Great War entailed. Both the Dublin and Munster Fusiliers as well, as the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, had landed as part of the British 29th Division at Cape Helles during the Gallipoli Campaign in April 1915. The Dublin and Munster regiments suffered such casualties that they were subsequently amalgamated into a single unit for a time. The 1st Battalion of the Dublin Fusiliers lost six hundred men from a total force of one thousand over two days in the battle for the fortress and village of Sedd el Bahr.

All three of these units were moved to the Western Front in the interval between the Allied withdrawal from the Dardanelles and the opening of the Somme campaign on 1st July 1916. There they were stationed in the vicinity of the many regiments that were made part of the new 16th (Irish) Division.

This was a grouping of both established Irish comprised units of the British Army like the Connaught Rangers and Royal Irish Rifles, as well as newer groups established from the intake of recruitment from the Irish Volunteers in 1914. It also included many “British” regiments from cities like Liverpool and Newcastle that were in actuality made up almost entirely of emigrant Irish or men of Irish descent residing in those cities. Examples of these units were the Tyneside Irish, the King’s Liverpool Regiment, and the London Irish Rifles.

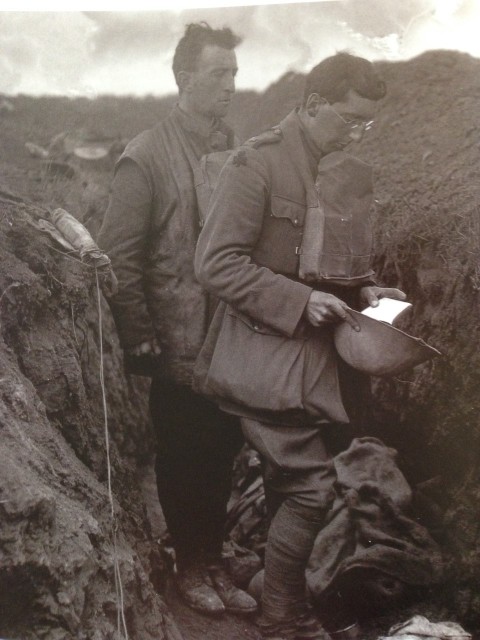

The Ulster Volunteer Force, meanwhile, had been formed into a division of its own – the 36th (Ulster) Division. It fell to the 36th to capture the Schwaben Redoubt near Theipval Wood on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, with their final objective for the day being the German position across a marshy valley floor near the River Ancre at Grandcourt. This task involved crossing no less than three separate German lines.

The Ulstermen completed their mission, capturing five hundred German prisoners, and held the high ground by nightfall, despite actually coming under fire from their own British artillery after capturing the first German trench. This complete success in capturing planned objectives was unique among all the British divisions that day; however, the price for their bravery was over two thousand dead with total causalities amounting to three and a half thousand.

The 36th was awarded a total of four Victoria Crosses for their actions on July 1st alone. But due the inability of the divisions on their flanks to make up the same amount of ground, the Ulster Division found itself in danger of encirclement and was forced to withdraw during the night and return to almost the same position it had started from the morning before.

The refitted Dublin, Munster, and Inniskilling Fusiliers also saw action on the first day of the Somme Campaign when they marched with the 29th Division and attempted to capture the Hawthorne Redoubt following the detonation of a massive underground mine (see footage). Poor timing allowed the Germans to take defensive positions in and around the mine crater and the Fusiliers suffered yet more causalities. The 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers, for example, lost over three hundred of the five hundred men they had begun the second wave of attack with.

The Tyneside Irish Brigade also suffered large casualties when they advanced in support of the 34th Division out of the Avoca Valley. The failure of the initial British attack in this sector meant that the Tynesiders were left completely in the open to machine gun crossfire, and they were effectively mown down before they even reached their comrades’ positions. Their causalities were over two thousand from a starting roll call of three thousand men – a rate of nearly 70%.

These numbers (total British losses in the opening day of the Somme numbered close to sixty thousand) meant that reinforcements were badly needed, and the 16th (Irish) Division was brought into action around the Somme theatre from their former position in the Loos Salient, where it had participated in the Battle of Halluch earlier in the year. The 16th took part in the Somme campaign from the 1st of September and it was instrumental in the capture of the towns of Guillemont and Ginchy.

Like the Ulster Division’s success at Theipval earlier that summer, the Irish Division’s capture of Ginchy was the only success that the British Army enjoyed that day, but the casualties involved were grim. The unit lost half of its officers and over four thousand casualties. Coupled with the comparable losses during the Loos campaign, and a drop-off in recruitment from back home, both the Irish division was reinforced by troops largely made up of a non-Irish background.

Both the 36th and the 16th would fight together at the Battle of Messines in 1917, and they would also see action in various roles at Passchendaele, Ypres, Cambrai and during the German Spring Offensive in 1918, the final German offensive to win the war before its home front collapsed. The 16th’s remaining Irish members were most likely killed during a German attack at Ronssoy at this time, giving the unit the dubious distinction of having a higher number of casualties than any other British division that year.

Though there were numerous instances of comradeship between men of the Ulster Division and those that came from the rest of Ireland, the unplanned period of truce and alliance of convenience against the Central Powers did not last. Already, in April 1916, nationalist republicans had staged a week long insurrection in Dublin; and although a failure initially, by 1918 the independence movement had developed into a full blown civil conflict.

Ireland was separated into the six counties of Northern Ireland (from the total of nine that made up historic Ulster) and the twenty six county independent state that is now the Republic of Ireland in 1920. The war in Ireland would last for another two years before a peace treaty was signed between the British and Irish governments in 1922, and the three parliaments of Dublin, Belfast, and London finally confirmed the settlement of the land border in 1925.