Thomas Edward Lawrence is one of the most mythologised officers in modern history. A biography by a journalist, his own writings, and a film about his exploits have given his story an air of grandeur and a sense of unreality. His exploits, although exaggerated, were real. He was a key Allied player in the First World War and an extraordinary leader of deeply divided loyalties.

Origins of an Officer

Born in 1888, Lawrence was the son of an Anglo-Irish baronet and the family servant he eloped with. After private schooling, Lawrence went to Oxford University. Fascinated by medieval history, he studied crusader castles for his thesis, along the way learning a great deal about Arabic culture and language.

Following his degree, Lawrence traveled to the Middle East, where he led archaeological digs. These were often in dangerous and lawless areas, showing the daring that was his hallmark.

Cairo

In the summer of 1914, Lawrence was part of an archaeological dig that acted as cover for intelligence gathering in the Sinai. The area was controlled by the Ottoman Turks, who were aligned with Germany and Austro-Hungary.

When the war was declared, Lawrence joined the army. He was posted to the intelligence division in Cairo. There, his local knowledge, language skills, and experience from the previous summer were put to good use. Staffed mostly by intellectuals, eccentrics, and characters, the Cairo intelligence division suited Lawrence.

The Arab Bureau and Iraq

The British realized they could not spare enough resources to fight Turkey. Instead, their best hope was to support an Arab revolt against the Turks. In January 1916, the Arab Bureau was set up to make it happen. There were rumors of Britain supporting Arab independence.

Lawrence, a fan of the Arabs, was delighted.

His first field mission was less delightful. He was sent to encourage an Iraqi revolt in support of British troops at Kut. He discovered the affair was a shambles, and the British deluded in believing that Iraqi soldiers would rebel.

Hussein’s Revolt

A better prospect arose in October 1916, when Lawrence met with Sheik Hussein of Mecca, who had rebelled against the Turks. Lawrence became friendly with Hussein and his son the Emir Feisal.

Without outside support, Hussein’s revolt was at risk of collapse, but the British were loath to divert forces from elsewhere to help.

Rejected by Superiors, Embraced by Arabs

At the British field headquarters at Jeddah, Lawrence found himself in conflict with other officers. The colonel in charge disliked his scruffy appearance. Others saw him as a young upstart.

The Arabs, on the other hand, were delighted by this young foreigner. He was friendly, respectful of their customs, and represented the promise of British help.

Lawrence’s recommendation that the British supply technical support pleased everyone. The British government did not have to commit fresh troops to the uprising. Their supplies of guns, armored cars, and planes, along with local specialist support, were a huge help to the Arabs.

Soon Hussein was pushing the Turks back.

Attacking the Railways

As the Turks counter-attacked, Lawrence helped develop a new strategy. By attacking Turkish railway lines, the Arabs could cause difficulties for their opponents. It allowed British forces under Edmund Allenby to advance in Palestine, piling pressure on the Turks.

The result was a string of attacks on Turkish infrastructure. Often made by Arab forces led by Lawrence, these hindered the Turks. Aqaba surrendered to an advance from Lawrence and his comrades.

Keeping up Momentum

Lawrence worked hard to maintain momentum. Faisal was becoming demoralized at setbacks. The Arabs were prone to looting when they should fight and to fighting among themselves. Allenby made demands of Lawrence’s time and effort. Lawrence himself was captured at one point.

The effectiveness of Arab guerrilla raids became a matter of debate. Lawrence, eager to show the Arabs in a good light, pointed out the damage they had done on the railways. Critics said that supplies still got through.

Divided Loyalties

As 1918 rolled around, the initiative shifted firmly to the Allies. The Arabs worked more closely with British and Australian forces as they pushed the Turks back.

It created problems for Lawrence. His loyalties were divided between his British origins and his affection for the Arabs. His dual roles of acting as a liaison and leading Arab raids added to the pressure.

Close cooperation caused clashes between the allies. The Australians and British respected their Turkish opponents more than they did the Arabs. Many Arab warriors were opportunists who avoided fighting but turned up for the looting. Lawrence was repeatedly forced to defend his friends from the criticisms of his colleagues.

Damascus and Versailles

Politics added to the tensions. Britain had recently promised support for a Jewish homeland in the Middle East, which would impinge upon Arab lands. Rumors emerged of another agreement, this one between the British and the French, to divide the region between them.

British support for Arab independence seemed half-hearted at best.

It reached its symbolic climax after the fall of Damascus. Lawrence had planned a triumphal entry into the town for Faisal. Allenby prevented it and side-lined the Arabs in the victory celebrations.

During the Versailles conference that followed the war, Lawrence used his fame and influence to support Faisal’s cause. Little was achieved; the Arabs had been betrayed. They would not have their freedom.

Publicity and Anonymity

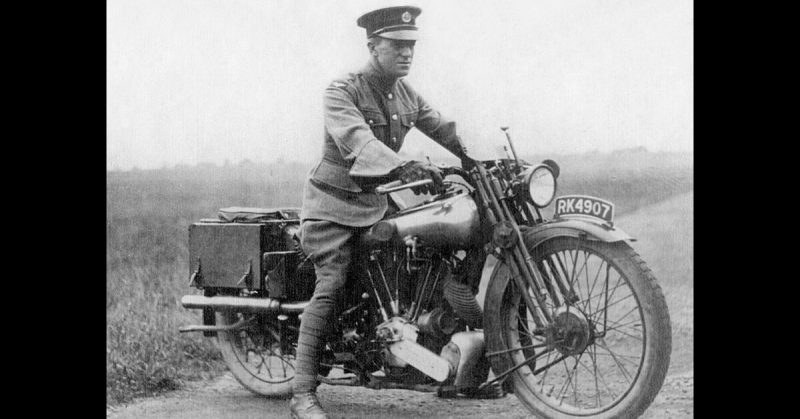

After the war, an embittered Lawrence found himself divided. He wanted to tell people about the Arabs and what he had achieved, but he found the glare of publicity stultifying. He left the army, serving instead in the RAF and then tanks, on both occasions under false names.

In May 1935, he crashed his motorbike near his home in Dorset and was fatally injured.

He had achieved great fame working for both the British and the Arabs. However, both were a disappointment to him, and that betrayal overshadowed his later life.

Sources:

Richard Holmes, ed. (2001), The Oxford Companion to Military History.

David Rooney (1999), Military Mavericks: Extraordinary Men of Battle.