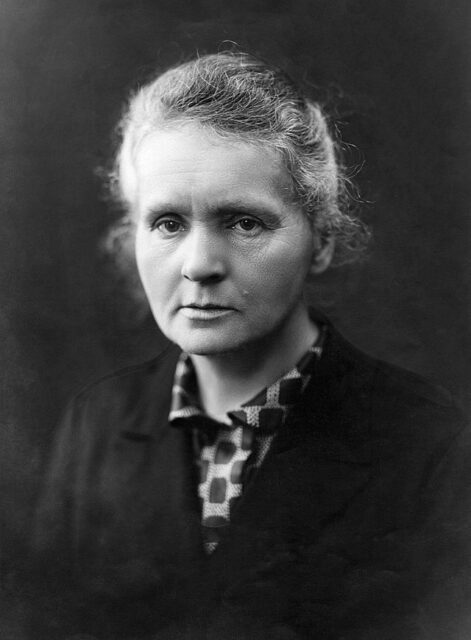

Marie Curie is considered one of the most accomplished scientists of the 19th and 20th centuries. Her discovery of radium and polonium helped win her the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903, alongside her husband, Pierre. Just eight years later, she won the prize again, this time in Chemistry.

While her work garnered a lot of praise, it also allowed her to be of use to those who were on the frontlines during World War I

Marie Curie was looking to join the war effort

When the fighting broke out in 1914, Marie Curie was residing in Paris with her daughter, Irène. While wanting to continue her research, she found she only had one gram of radium at her disposal. Knowing it wouldn’t be enough and that she wouldn’t have access to more until after the war, she transported it to Bordeaux – which had been named the temporary capital of France – and locked it in a safety deposit box.

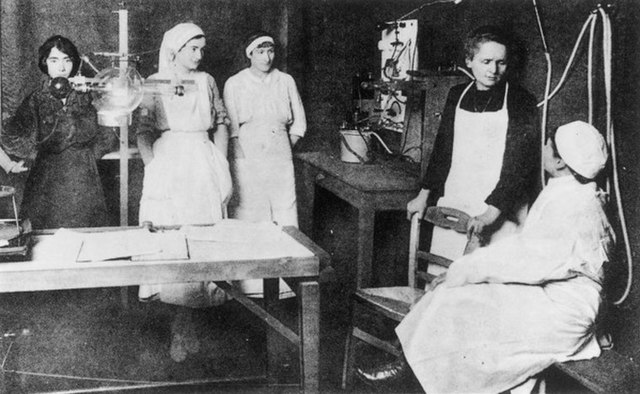

As the founding director of France’s Red Cross Radiology Service, Curie set up a laboratory at the Radium Institute. It was around this time that she found herself wanting to be of more use to the war effort. She noticed military doctors on the front were in need of X-ray technology to better help treat soldiers who’d been injured in combat.

While the technology had been around since 1895 when it was discovered by Nobel laureate Wilhelm Röntgen, it was still largely limited to use in city hospitals. Aware of this, Curie decided she would come up with a way to make it mobile.

Mobile units are developed

Despite lecturing about X-rays at Sorbonne University, Marie Curie had never actually worked with them. She took courses to ensure she’d be able to properly man the equipment and read the radiographs. She also learned to drive and perform basic car repairs.

The mobile units featured a hospital bed, an X-ray machine, photographic darkroom equipment and an electrical generator. Curie used a dynamo generator for the latter, as it allowed the car’s engine to provide the necessary electricity. She petitioned wealthy friends for money and vehicles, persuaded French manufacturers to donate their X-ray technology and asked local body shops to outfit it all.

Curie then turned her attention to recruiting people to operate the equipment. She and Irène began by training 20 women at the Radium Institute. By the end of the First World War, 150 had been trained to provide radiological diagnoses to troops.

Deploying the mobile units to the Western Front

Despite their obvious usefulness, Marie Curie had to sell the French Army on the mobile units. In October 1914, she, Irène and a military doctor traveled to the Marne, where troops were waging a battle against the Germans. The engagement wound up being a major Allied win, preventing the German invasion of Paris.

After this, 20 mobile units were sent to the frontlines. As word spread, they began to be nicknamed the Petites Curies – or “Little Curies.” Curie also set up 200 stationary X-ray units at more permanent military posts to ensure aid was evenly distributed across France. When the war came to an end in November 1918, over one million French soldiers had benefitted from the presence of the Petites Curies on the front.

Many of the women who’d run the fleet suffered burns, due to overexposure to radiation. While Curie was aware of some of the associated health risks, she’d had no time to perfect proper safety practices. She worried about this later in life, and it led her to write a book on X-rays and wartime radiography, drawing heavily on her experiences during the war.

Marie Curie’s later life

Marie Curie’s post-war life saw her continue her research. She traveled across the world to raise funds, and eventually joined the League of Nations International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, alongside the likes of Albert Einstein and Henri Bergson.

Curie garnered more recognition during this time. She was awarded the Cameron Prize for Therapeutics by the University of Edinburgh in 1931, and served on the International Atomic Weights Committee until her death.

Irène eventually won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry herself, alongside Curie’s son, Frédéric.

More from us: Iva Toguri D’Aquino: The ‘Tokyo Rose’ Who Tried to Help the Allies and Was Convicted of Treason

Curie passed away in 1934, at the age of 66, from aplastic anemia, a condition caused by the body’s inability to produce enough red blood cells. While many attributed it to her contact with radium, Curie quickly countered, saying she’d taken the necessary precautions to ensure she handled the radioisotope safely. She instead attributed her illness to the overexposure she’d received working with the Petites Curies during the First World War.