The Treaty of Versailles was one of several peace agreements that signaled the end of World War I; it sealed the end of the conflict between Germany and the Allied powers. The conditions laid out within it aimed to prevent another war from occurring, but most will argue that it did the opposite. Here’s everything you need to know about this historical document and the conference that led to its signing.

When was the Treaty of Versailles signed?

The hostilities of the First World War came to an end at last on November 11, 1918, following a series of Armistices across Europe. Early the following year, the process of negotiating peace began with the opening of the Paris Peace Conference. Involving victors of the conflict (AKA, the Allies), it kicked off on January 18, 1919, and lasted a year, ending with the inaugural meeting the League of Nations on January 16, 1920.

Key Dates:

- January 18, 1919: Paris Peace Conference opens.

- June 28, 1919: Treaty of Versailles is signed.

- January 16, 1920: Paris Peace Conference Conference closes with the inaugural meeting of the League of Nation.

Where did the Paris Peace Conference take place?

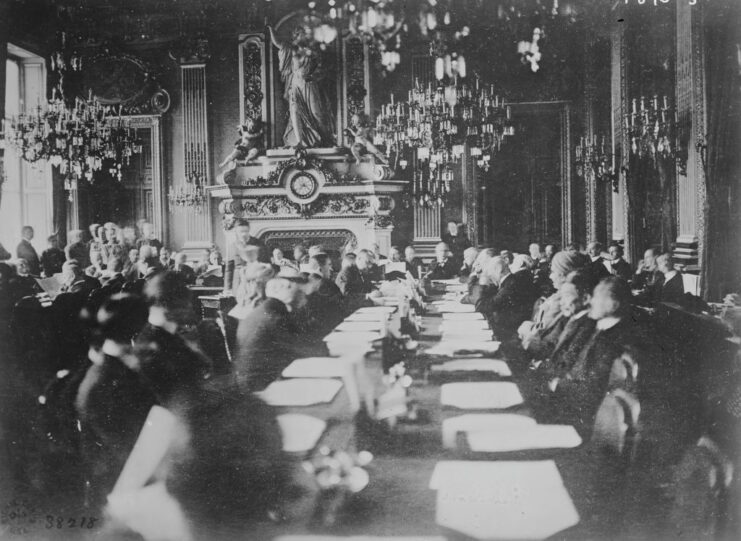

The Paris Peace Conference took place at Versailles, just outside of the French Capital. The sumptuous Palace of Versailles had been the scene many meetings and negotiations already; it was famous, as it had once been the home of the extravagant French monarch, King Louis XVI, and his wife, Marie Antoinette.

It would soon give its name to the most famous document to emerge from the conference: the Treaty of Versailles. The agreement was signed in the Palace’s famed Galerie des Glaces – “Hall of Mirrors.”

Who were the key players?

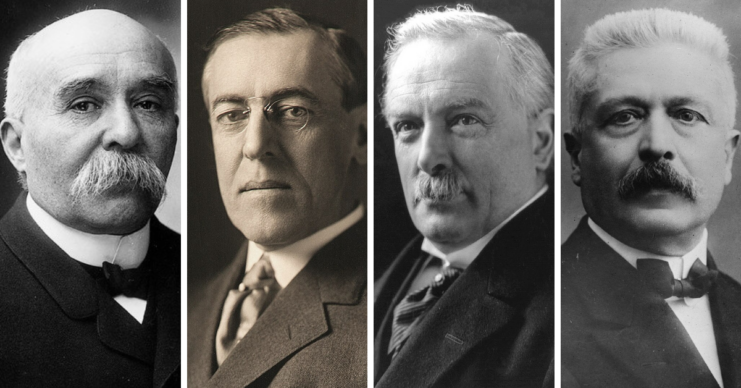

The key players were the representatives of the countries who’d emerged victorious after years of fighting in Europe and beyond. The so-called “Big Four,” who held the majority of power at the negotiating table, were:

- David Lloyd George – prime minister of the United Kingdom

- Woodrow Wilson – president of the United States

- Georges Clemenceau – prime minister of France

- Vittorio Emanuele Orlando – prime minister of Italy

However, some would say that the “Big Three” – representing the United Kingdom, the United States and France – held the real power, with Italy playing a much smaller role.

They’d originally been the “Big Five” and included Japan, but the nation gave up its place at the table. Japan’s two main concerns were racial equality and the restoration of its former territories in China and the Pacific, which, until the end of the war, had been under German control.

In addition to these major powers, many other countries were represented, and each tried to negotiate the best possible outcome for post-war recovery. Over 30 nations were represented, negotiating 52 commissions. During the 1,646 sessions that took place, they prepared reports and documents and called upon the specialist knowledge of international experts on several important topics, including prisoners of war (POWs), international aviation and, perhaps most crucially, the responsibility for the conflict.

What brought about the Paris Peace Conference?

When the final Armistice was declared in November 1918, the world could never return to the way it had been before the Great War. New alliances had been formed, huge debts had been accrued to pay for the fighting and the terrible human cost led to a great depletion of the workforce, making it even harder for countries to recover.

It was also felt that there was a need for retribution and compensation, so the many suffering nations could feel as though justice had been served. Just as importantly, there was the more idealistic ambition to put measures in place to ensure that a war on this scale could never again take place. Balancing these different needs along with the claims of many different countries wasn’t going to be an easy task.

Even the three top negotiators – the United States, the United Kingdom and France – had competing priorities and different ideas about how best to achieve lasting peace. Amongst them, France had experienced the most direct consequences of Germany’s actions. It had suffered invasion and occupation, whereas the other two hadn’t. As such, Georges Clemenceau wanted retribution.

France felt Germany ought to be punished for its actions and should pay for the damage it had caused. In addition, Clemenceau wanted the country to be severely weakened, to ensure it would no longer pose a threat. The US, on the other hand, was more focused on achieving peace. When Woodrow Wilson outlined his Fourteen Points in a speech to the US Congress in January 1918, the focus was on reducing armaments worldwide and self-determination for nations, rather than revenge and retribution.

The United Kingdom had suffered directly, particularly from German bombing raids, but not to the same extent as France had. Perhaps, for this reason, Lloyd George took the middle ground, trying to balance demands for justice and compensation with a need to ensure the safety of all nations and prevent future wars.

What did the Paris Peace Conference achieve?

After almost exactly a year of discussions and negotiations, the groundwork was laid for five major peace treaties, the most significant being the Treaty of Versailles. Published in English under the title Treaty of Peace, this document was primarily concerned with future relations with Germany (its allies were dealt with in other smaller treaties).

The signing took place on the fifth anniversary of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which had been the spark that had ignited the First World War. The most significant of its provisions was the “War Guilt Clause,” which required Germany and its allies to accept responsibility for all loss and damage caused by the conflict.

In practical terms, this meant Germany was forced to disarm, give up large parts of its overseas territories and pay reparations to the countries that had previously formed the Triple Entente: Russia, France, the United Kingdom and Ireland. The sum required to meet these costs was 132 billion gold marks.

Even at the time, opinion was divided on these measures. Some claimed they were too harsh and would be counterproductive, while France thought them too lenient. While the “War Guilt Clause” was intended to reduce the threat of future aggression by Germany, many historians have argued that it had the opposite effect.

The burden of repayment led to internal instability in the decades that followed. Combined with the desire to regain some of its former territories, this created the ideal conditions for the unrest, which fueled Germany’s descent into Fascism and, ultimately, the Second World War.

More from us: 24 Rare Photos That Give Us Another View of World War I

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

It’s easy to argue with hindsight that the desire for retribution was placed above the higher ideal of securing world peace. Unfortuantely, the mirrors of the Palace of Versailles’ Galerie des Glaces could only reflect the present, not the future.