During the Franco-Prussian War, French irregulars known as Franc-tireurs meaning “free shooters” terrorized German regular formations. The legacy of these partisans would continue to be in issue for German units in both the Great War and World War II.

German forces in World War 1 fought tenaciously to the last, enacting a brutal pragmatism that would become the norm for future warfare across the globe. With the Eastern Front more or less assured thanks to Russian incompetence, the Western Front proved a far tougher nut to crack.

Pragmatic and focused, the German mindset’s difference from that of the Entente’s created a divide that has only recently become understood by historians.

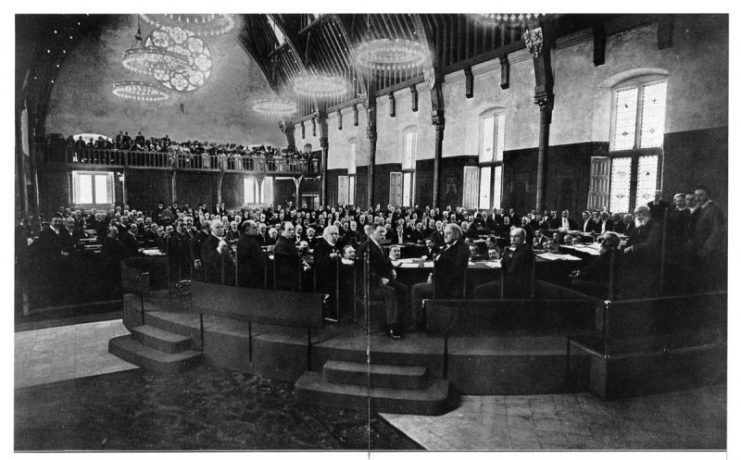

The Hague Convention of 1907, a precursor to the Geneva Convention and an attempt to designate what constituted a war crime, or lacking the term at the time, an “atrocity”, was a hallmark of the Entente’s efforts to civilize modern warfare, once acknowledged by fellow signatory the German Empire.

To the less autocratic nations of Europe, things like killing surrendered or wounded enemy soldiers, taking and killing hostages in retaliation for civilian attacks or presumed civilian attacks, and pillaging and burning towns were all atrocities and illegal actions as put forth by the Hague Convention.

On the other side was the German argument. Though it did not contest any of these actions as being an atrocity, and as mentioned signed the Convention, the Germans did believe that such sentiments as the Hague Convention had to be tempered against military pragmatism.

The German viewpoint held that sniping and ambush by individuals or by irregular forces against “loyal soldiers” constituted an outrage and justified the severest repression. In effect, they upheld military authority against the specter of civilian anarchy and insurgence.

In this, the philologists adopted the same position as the ninety-three German professors in their declaration of October 1914, when they denied that German conduct of the war infringed any international law and claimed the necessity of “bitter self-defense” (“bitterste Notwehr”), for “in spite of all warnings, again and again the population fired on [the German troops] from hiding.” These acts of “treacherous” civilian resistance incurred “just punishments.”

Thus rose the specter of the francs-tireurs, the famous French guerillas who plagued the German war effort in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871.

A statement drafted on August 12, 1914, by the Chief of the General Staff, Helmuth von Moltke, nephew of Moltke the Elder of Franco-Prussian fame, warned France and Belgium that resistance by civilian “francs-tireurs” was taking place, “just as was the case in 70/71,” and that it would entail summary executions and the indiscriminate burning down of “towns or villages from which German troops were fired upon.” Moltke explained that it was “in the nature of such things that [the military countermeasures] will be extraordinarily harsh and even, under [some] circumstances, affect the innocent.”

The troops on the ground seemed to share this view. The journal of one German soldier noted that “nocturnal nervousness about ambush was growing and hostages were taken as a security measure.” On the night of August 22, near intense fighting along the Meuse, the diarist noted a house on fire, “doubtless to betray our position.”

Whether the fire was intentional or not, the soldiers on the ground clearly shared their commander’s paranoia. The fear of French partisans, combined with the already ingrained fear that Germany was surrounded by enemies –the French in the West and Russia in the East- created for a brutal pragmatism many in the Entente and beyond considered excessive.

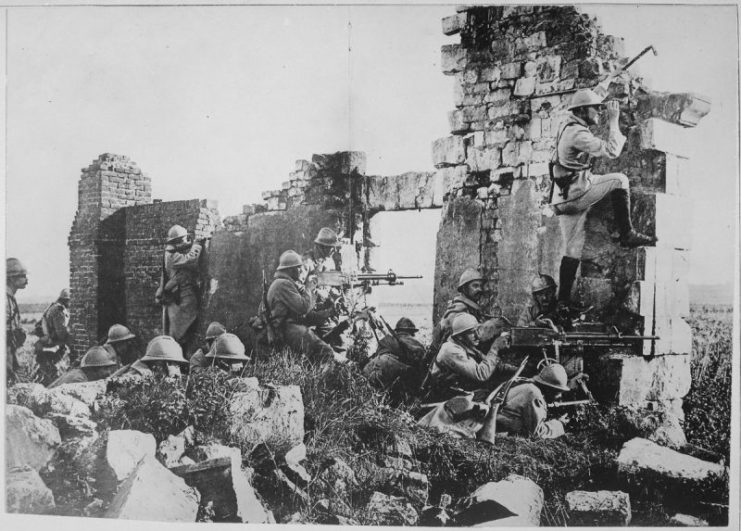

An incident of such paranoid pragmatism occurred on August 23, 1914, in the early mobile phases of the Western Front. A regiment was advancing toward Fresnois-Montigny without coming under attack. Then, from over 500 meters away, heavy firing burst out from the first houses in Montigny.

The men’s commander, taking cover behind a haystack, saw how his men, who assumed that local partisans must have opened fire, “stormed wildly into the village.” The men set Montigny on fire, though at such distances distinguishing who was actually shooting would have been impossible without eye enhancement.

The brutal pragmatism of the German Army in World War I did not endear it to the locals, neutral nations, or, as the war ended, the victorious nations. However, with hindsight, in light of the many atrocities different nations have committed, the only real difference between the German’s and their enemies were that they did it first, and against fellow Europeans at that.

Works Cited:

Horne, John and Kramer, Alan, “German “Atrocities” and Franco-German Opinion, 1914: The Evidence of German Soldiers’ Diaries.” The Journal of Modern History, 66, No. 1 (Mar., 1994).