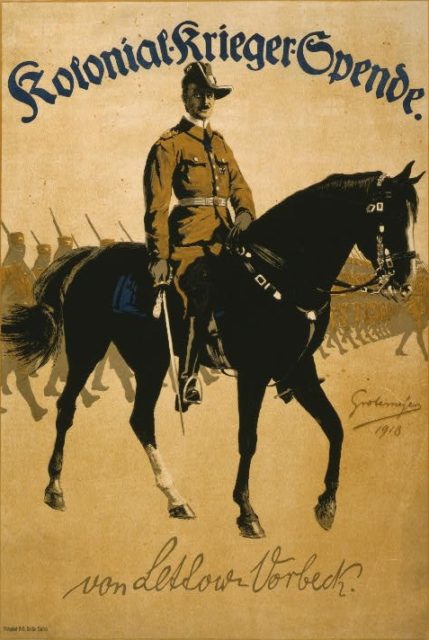

In March of 1919, while Germany was recovering from its defeat in the First World War, its people starving and its army in ruins, a victorious hero returned home. Mounted on a black horse, in a well-worn khaki cotton uniform, and followed by 120 officers dressed the same, General Paul von Lettow- Vorbeck marched through the Brandenburg gate. His legacy had begun five years before, as the commander of the German Schutztruppen, their colonial force in East Africa.

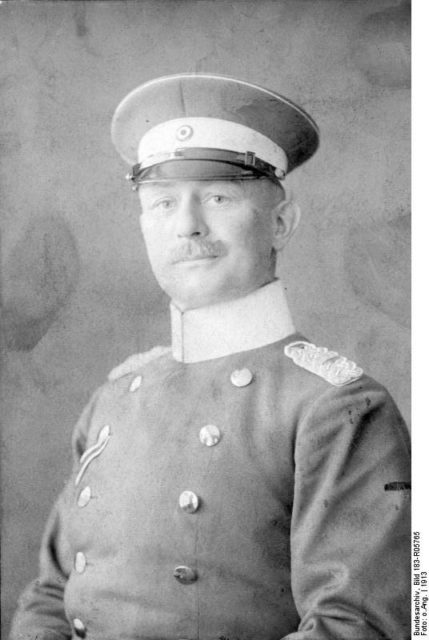

He began his military career in 1890 after graduating from a military boarding school. He then received a Lieutenant’s commission in the Imperial German Army. After seeing action in the Boxer rebellion, he returned to Germany as part of their general staff.

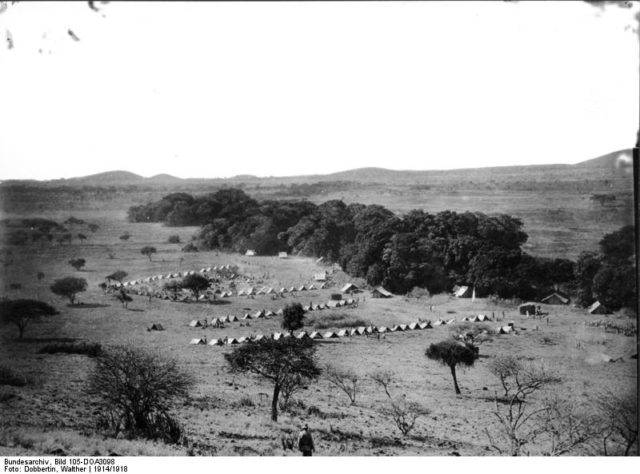

By 1914 he had been promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and was posted to German East Africa. He was now in command of a local protection force of around 5,000 troops, and the Great War was about to erupt.

In August 1914 war was declared. At first, it was believed that the Congo Act of 1885 would remain in effect, and all European colonies would remain neutral.

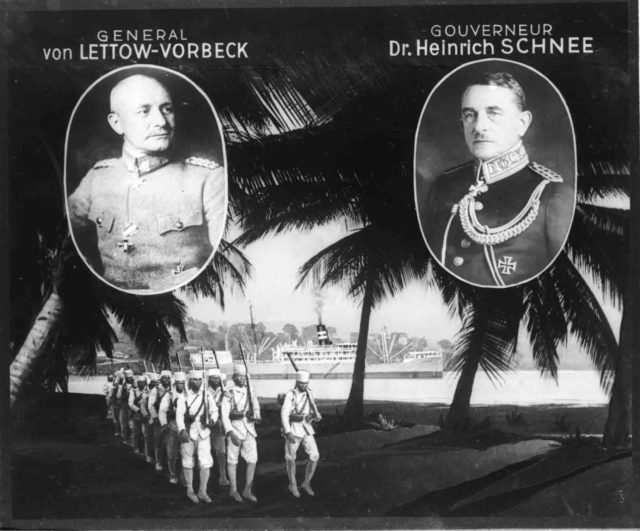

Lettow- Vorbeck immediately clashed with his superior, the governor of German East Africa Heinrich Schnee, over this. Lettow-Vorbeck wanted to take the war to the enemy, and hopefully draw troops away from the main front in Europe. But Schnee forbade this, believing that a peaceful neutrality was still possible in the colonies. Lettow-Vorbeck almost immediately began his policy of ignoring any and all of Schnee’s wishes.

Early in November 1914, Lettow-Vorbeck was proven right; an offensive campaign was necessary, and the British weren’t going to respect the colony’s neutrality. He caught wind of an invasion coming, aimed at the town of Tanga. He reinforced the town’s original garrison, eventually gathering around 1,000 men.

When the British landed, they had an 8,000 man force, and came ashore unopposed. They continued their advance inland, eventually taking much of the city, but that’s when Lettow-Vorbeck’s men counterattacked. Amid bugle calls and war cries the Germans charged the advanced British positions with bayonets. The British Indian troops broke and routed, retreating to HMS Fox, anchored in the harbor. The Germans had won their first victory in East Africa.

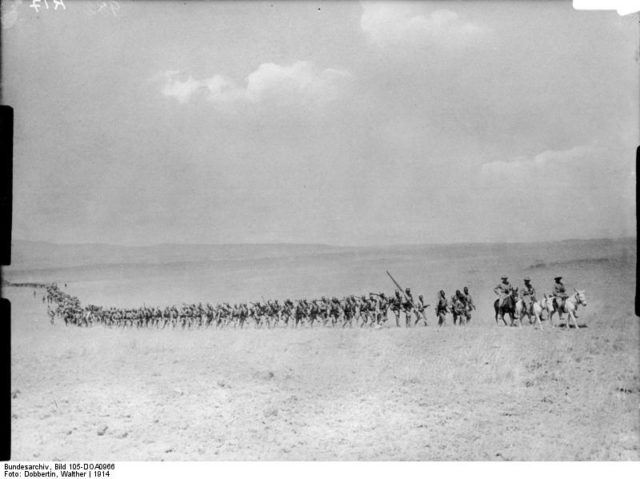

Lettow-Vorbeck knew to draw troops away from Europe that he needed to go on the offensive, and in January 1915 he marched north to Jassin. With 1,600 troops he took the rail and supply depot there. His men were armed mostly with outdated black powder rifles from the late 1800s, some even using the Gewehr 1871.

If they were to compete with a well equipped English, Belgian or French force the needed modern weapons. Jassin provided those weapons, but at a high cost. Believing that his numerical superiority would afford him an easy victory, Lettow-Vorbeck used a frontal assault, which, while successful, led to high casualties. He knew that his tactics would have to change, and from then on, he would avoid open battles.

Over the next three years, Lettow- Vorbeck and his troops would embark on one of the most successful guerrilla campaigns in history. He had a strong cadre of competent officers, most of whom would willingly lay down their lives for him. He encouraged all of them to attack targets of opportunity, from a single telegraph line to a rail yard. Everything was fair game.

His officers obliged, leading a stream of attacks against any target they could reach. The British were knocked off balance and were unsure of the actual size of his forces. While this tactic was effective in the short time, it also led to high casualties, though this time from his Officer Corps, who often led from the front.

As their presence and prestige grew they started recruiting more troops, eventually raising an additional 14,000 men. In addition to this, he had the crew, equipment, and weapons from SMS Koenigsberg, a cruiser which was scuttled off of the East African shore.

After remounting her guns on mobile carriages, he had the largest field artillery in the region. But with success, as always, comes attention and the British had to respond to them eventually.

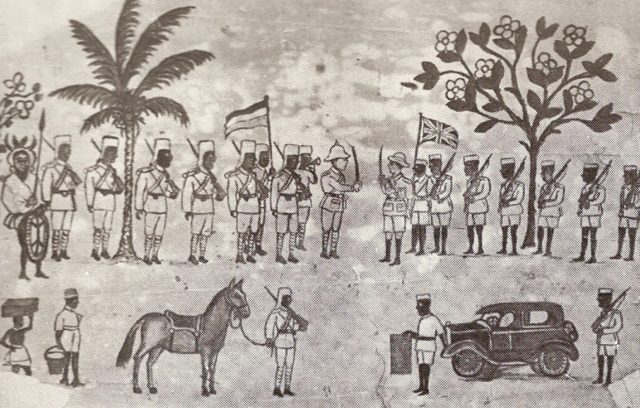

In September 1916, a 48,000 man force, of combined British and Belgian troops marched into German East Africa. Major Kurt Wahle, one of Lettow-Vorbeck subordinates, made the first contact, with a group of 5,000 against an attack twice that size.

He was forced to retreat and rejoin the fighting column, which began leading the allied force on a wild goose chase around the plains. The Germans would take a small village, depot, or supply dump, then move out before any enemy could arrive. This allowed them to remain well supplied while still tying up British troops.

This went on for almost a year of small skirmishes, feints, complex maneuvering, and expert military leadership. But in October 1917, Lettow-Vorbeck was attacked at Mahiwa. His 1,500 man force was up against an English one of 4,700. While the English couldn’t advance on his positions thanks to accurate machine gun and rifle fire, the Germans took high casualties.

The English suffered a whopping 2,700 killed or wounded, the most in the region since the Battle of Tanga in 1914. The German troops suffered 519, paltry in comparison, but over a third of their total force. What’s more, they had expended nearly all of their smokeless powder cartridges in the battle. Lettow-Vorbeck’s troops went back on the move, marching south.

They became nomads, crossing the Ruvuma River in November 1917. This put them in Portuguese territory and completely cut their ties with the outside world. They were on their own, marching around in hostile territory. But they soon found the fort at Ngomano. They took the fort easily and found that it had just been resupplied. They restocked their ammunition and weapon supplies, filled their bellies and rucksacks, and marched back out into the wilderness in search of another target.

His men continued like this, taking villages, towns, and supplies as they went. They took the town of Namakura in July of 1918, again relieving any supply problems. At this point, they had been so successful they had more ammunition than they could carry.

After Namakura they began marching back up into German East Africa, but scouts spied a British force waiting for them near the frontier. They instead swung west, and took the town of Kasama, on November 13th, 1918.

This was two days after the armistice was signed, and the war was supposed to be over. But the news hadn’t reached this roving band of soldiers. The next day, while heading for another town, they saw a white flag approaching their column. Beneath it was the British Magistrate for Rhodesia, Hector Croad. Mr. Croad presented, now Lieutenant General, Lettow-Vorbeck a letter from British General Jacob van Deventer. It informed him of the armistice’s signing, the end of hostilities, and Germany’s defeat.

Being a gentleman, and knowing when there is no other course of action, Lettow-Vorbeck marched north to the British outpost of Abercorn to surrender properly. By this point his almost 15,000-man force was reduced to 20 officers, 120 German non-commissioned officers and enlisted men, and around 1,168 native Askaris.

When he returned home to Germany, he and his men were given a hero’s welcome. They were the last major German force to surrender, and they had become folk heroes for their exploits in the exotic East African Theater. Despite their high casualty rate, and lack of supplies, they were never fully defeated in combat, and instead demonstrated the ability of even a large force to outmaneuver, out-think, and out-march its opponent, leading to one of the most effective guerilla campaigns in history.