In WWI the German Empire was on the rampage. Europe has always existed through a complex network of alliances. When Germany united in 1871, it absorbed Prussia, and by 1879, had entered an alliance with Austria-Hungary to counteract Russia and its influence over the Balkans. By 1882, that agreement included Italy.

Russia reacted by entering the Franco-Russian Alliance eight years later, and in 1904, Britain signed the Cordial Agreement with France. In so doing, Britain and France ended almost one thousand years of intermittent conflicts between them.

Then in 1907, Britain signed the Anglo-Russian Convention. The result was not an Anglo-Franco-Russian alliance, per se, but the Triple Entente made it likely that each was going to help the other in the event of war.

More specifically, a war against Germany, because that nation had grown industrially and economically since its unification. By the mid-1890s, the German emperor had begun expanding the Imperial German Navy, making Germany a potential rival to British and French maritime supremacy.

By the start of the 20th century, Britain and Germany were locked in an arms and industrial race. Perhaps sensing what it was leading to, the major European nations increased their military spending by up to 50% between 1908 and 1913. All that arms buildup was just waiting for a spark.

That spark came from the Balkans – Europe’s traditional powder keg since the decline and fragmentation of the Ottoman Empire. The assassination of Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand in the Bosnian capital by Serbian nationalists became the fuse that set in motion a deadly chain of events.

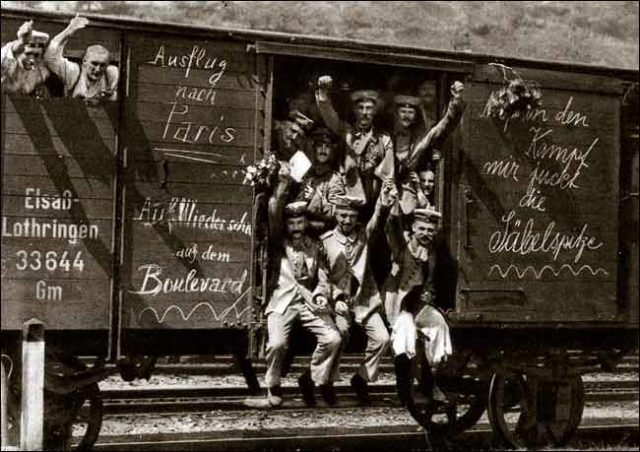

In retaliation for the assassination, Austria threatened to invade Serbia. Russia, siding with Serbia, began mobilizing, so Germany declared war on Russia and tried to get France to stay neutral. France was still furious at losing territory to Germany during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), and so WWI began.

Robert C. Campbell was born in Punjab, British India in 1885. In 1891, the family moved back to Britain, settling down to a comfortable life in Bedford. Campbell was 18 when he joined the British Army in 1903, and when WWI began in 1914, led the First Battalion East Surrey Regiment.

In August 1914, they were in Le Havre, France assigned to the 14th Brigade, 5th Division of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). By the end of the month, they were fighting the Germans along with the French Fifth Army. They were defeated at the Battle of Charleroi on August 23.

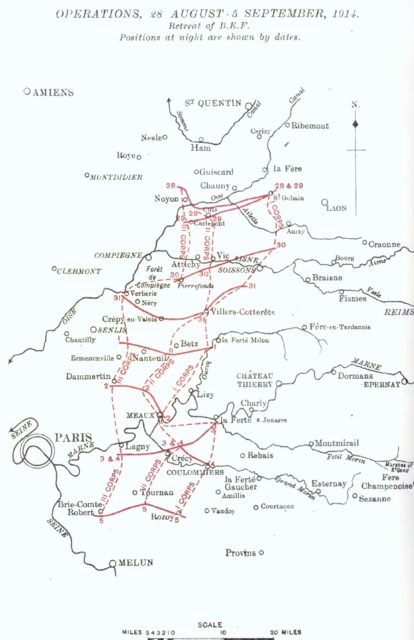

The First Battalion were at the Mons-Condé Canal trying to stop the German 1st Army from moving deeper into northwestern France. The Germans focused on the British massed at the salient in the canal’s loop. At 9 AM they tried to cross four bridges but were pushed back. The Germans repeatedly attacked, and by noon, the British could no longer hold their position. The German IX Corps crossed the canal and attacked the British right flank. By 3 PM, it was hopeless, so the British 3rd Division were ordered to give up the salient.

Campbell’s men went to the south of Mons, hoping to establish a new defensive position to hold back the German tide, but it was useless. They had built pontoon bridges over the canal and were swarming over in significant numbers. By the evening of the next day, the BEF retreated further to their defensive lines on the Valenciennes–Maubeuge road.

The BEF were heavily outnumbered. Even the French Fifth Army began falling back. What followed was the Great Retreat – also called the Retreat from Mons. The Allies began moving back from the advancing Germans, rallying at the Verdun-Rheims-Paris line – a process that continued until September 28.

About a week into the Great Retreat, Campbell was severely injured and was captured by the Germans. He was sent to a military hospital in Cologne, Germany and then to the POW camp at Magdeburg, also in Germany.

He spent the next two years there, together with about 10 million other servicemen and civilians. During 1916, he received a letter via the Red Cross that his mother was dying of cancer. Desperate, and with no other options, Campbell did the only thing he could.

He wrote to the German Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, asking permission to see his mother. To his surprise (and no doubt, everyone else’s), the emperor replied and granted his wish. He was granted two weeks leave on condition that he gave his word as a British Army officer that he would return. A German POW Peter Gastreich asked for permission to see his dying father, but the British government denied his request.

The details of how Campbell managed it, exactly, are unknown, but it is believed he went to the Netherlands – which was neutral territory. From there he caught a boat to Kent and made his way to his mother’s house. How he returned is also a mystery, but return he did.

Campbell went back to the Magdeburg POW camp. Once there he and several other POWs spent nine months digging a tunnel to escape. They made it as far as the Dutch border before they were caught and sent back.

Asked why he returned to Germany, Campbell said he had given his word as an officer and a gentleman. Asked why he then tried to escape a place he voluntarily returned to, he claimed that it was also his duty as a British officer to do just that.