When the British Royal Navy launched the HMS Dreadnought in 1906, battleship design was transformed. This one ship was so powerful that everything preceding it was immediately out-classed. Superpowers rushed to build ships in the new dreadnought class. But when the First World War broke out eight years later, a large part of their navies still consisted of pre-dreadnought ships.

Not Quite Obsolete

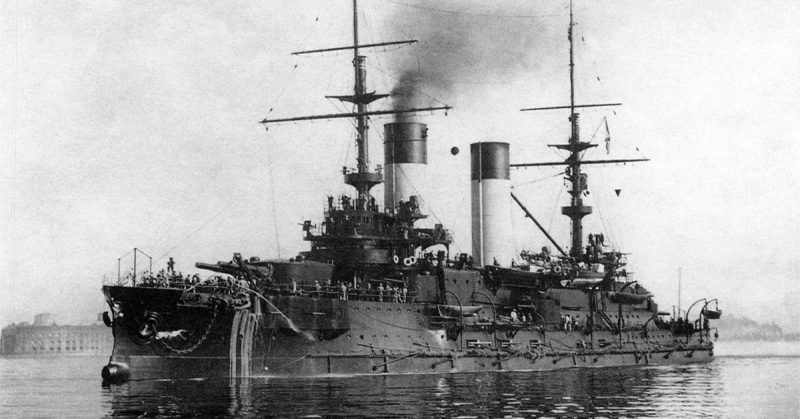

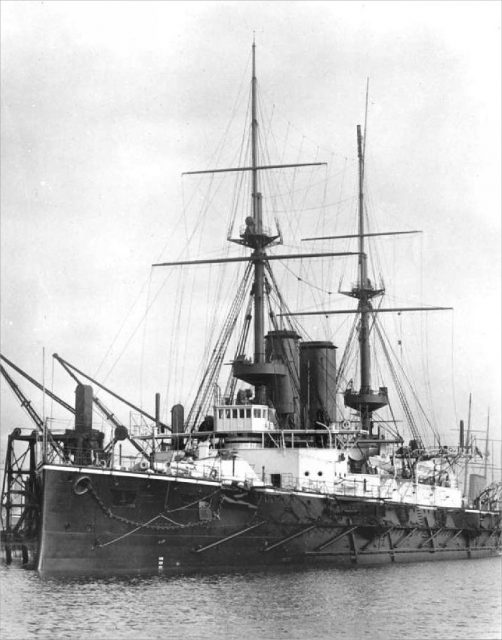

Pre-dreadnought battleships were impressive pieces of engineering, vast floating fortresses carrying powerful artillery. They had been hugely costly to build, and up until 1906, they would have been able to dominate any naval confrontation.

The problem was that dreadnoughts were so much more powerful. Their superior modern engines gave them better speed and maneuverability. While older battleships carried main armaments in a mix of sizes, those on the dreadnoughts all consisted of the heaviest possible naval guns, giving them a massive advantage in combat. Their sheer size meant that they could endure a greater pounding and still fight on.

The older battleships were out-classed, but not yet completely obsolete. A pre-dreadnought battleship might be vulnerable to the power of its successors, but it was still better than no battleship at all. Navies could not afford to simply discard such expensive pieces of equipment.

And so, though dreadnoughts dominated, pre-dreadnoughts played a part in World War One.

What Were Pre-Dreadnought Battleships Like?

Pre-dreadnought battleships came in a range of designs, varying with the priorities and resources of nations and designers. They also varied in age. The two most important naval powers of the war, Britain and Germany, fielded battleships built between 1892 and 1908. Advances had been made during that time so that more recent ships were generally better. But certain similarities existed across the board.

Pre-dreadnought battleships usually had a displacement of 10,000-14,000 tons, compared with the 17,900 tons of the first dreadnought. Their engines were coal-fired, while many dreadnoughts had more powerful oil-fired engines. Pre-dreadnoughts also lacked the steam turbines introduced for the first time on the Dreadnought. Most had a top speed of 20 knots or less, significantly slower than their successors.

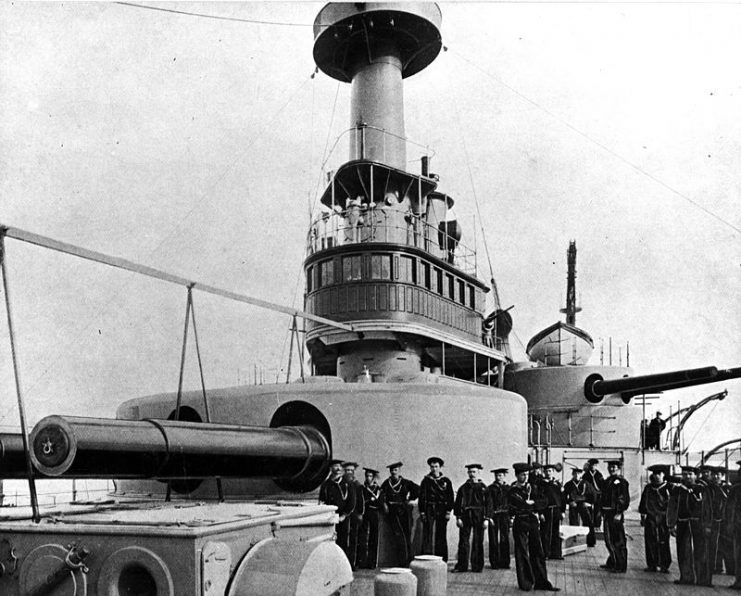

These ships usually had two sizes of naval gun. Their primary armament consisted of four main guns, of 12-inch caliber on British ships and 11-inch caliber on German variants. These were accompanied by between 10 and 14 lighter guns, like the dozen six-inch guns on the HMS Formidable.

Hundreds of sailors crewed every battleship. Command staff served on the main bridge, which was open to both the weather and enemy fire. The gunnery control position was raised high on a mast for better visibility, again leaving its crew exposed.

Allied Use of Pre-Dreadnoughts

The Allies had a substantial force of pre-dreadnought battleships. At the start of the war, Britain’s Royal Navy had 29 in active service and another 20 in storage. The French had 17 and the Russians nine. When they joined the Allied cause, the Italians brought another 8 battleships with them, the Japanese 23, and the Americans 16.

Because of its vast resources, the Royal Navy could afford not to use outdated ships in its main fleet. Pre-dreadnought battleships were quickly detached from the Grand Fleet, then serving in the North Sea, replaced by the growing number of dreadnoughts.

Many of these pre-dreadnoughts were sent to the Mediterranean, where the French and Italian ships were already based. This was a backwater compared with the North Sea, but still important in the war, as it was an arena in which Turkish and Austro-Hungarian movements could be contained.

Another way to effectively use these ships was for inshore bombardments. Such operations made the most of the ships’ firepower without opening them to attack by dreadnoughts. They were used in this way during the campaign in the Dardanelles, although their failure to smash Turkish shore defenses was an ill omen for the Gallipoli landings.

Central Powers’ Use of Pre-Dreadnoughts

The Central Powers had fewer battleships than their opponents. Germany could field over 20 pre-dreadnought vessels, Austria-Hungary 12, and Turkey only two.

The Turks and Austro-Hungarians kept their ships in the Mediterranean. There, they tied the French and Italian navies down for the course of the war, as the two sides threatened each other’s shipping routes.

The Germans faced the British across the North Sea, and this was always likely to see the great naval confrontations of the war. Unlike the British, the Germans did not have enough modern ships to leave their pre-dreadnoughts out of their main battlefleet, and so some were kept in the High Seas Fleet.

Six of them took part in the Battle of Jutland (1916), the greatest naval confrontation of the war and the only substantial clash between the great fleets. Despite their disadvantages, most of the pre-dreadnoughts survived the battle. Only the SMS Pommern was lost, going down with all hands after being hit by a torpedo.

There were enough German battleships to detach some from the main fleet. They made Germany’s presence felt in the Baltic, where they supported ground operations.

Going Down Fighting

The First World War was the last great showing for pre-dreadnought battleships. Though few saw the massive fleet actions for which they had been designed, they still played an important part in the war at sea.

Losses were higher on the Allied side – 11 British, four Russian, four French, two Italian, and one Japanese pre-dreadnought were lost. The Central Powers lost fewer – two Turkish, one German, and one Austro-Hungarian ship. But the Central Powers could not afford to take losses. For all their efforts, it was the Allies who dominated the seas.

The dreadnoughts made their predecessors obsolete, but they went down fighting.