The Western Front of WWI was fought mainly from defensive positions. They were not pre-built fortresses or border defenses. The boundary between the two sides emerged from a series of battles in September and October 1914. It was a Race to the Sea.

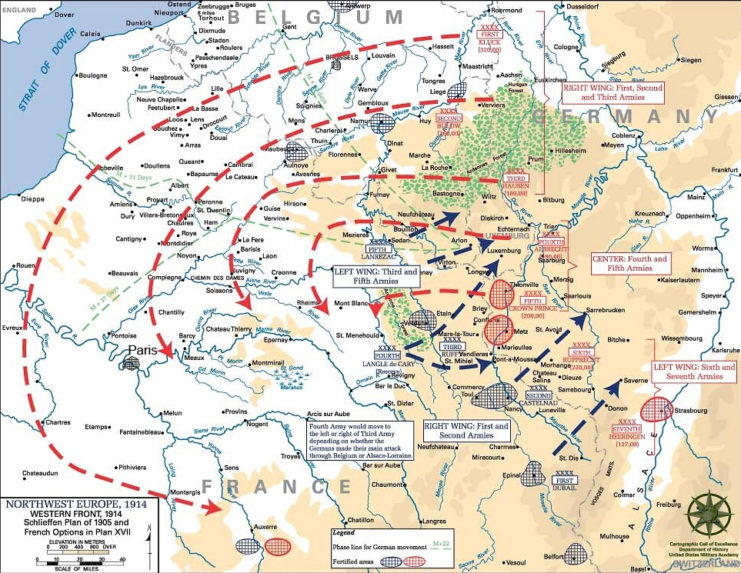

The Schlieffen Plan Fails

The war began using one of the most well-known plans in military history – the Schlieffen Plan. The Germans expected to march boldly and decisively into France, swing around the formations defending the country, and catch many troops between German armies.

The Schlieffen plan rapidly ran into difficulties. Once separated from Germany’s efficient railway network, the troops could not advance as quickly as expected. They became weary from marching and fighting.

The enemy had also put up a better fight than they expected, so the Germans were not able to mobilize as in the original plan.

In early September 1914, only a month into the war, Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke had to admit that his strategy – an adaptation of Count Alfred von Schlieffen’s original plan – was failing. He pulled German troops back north to the River Aisne.

It had two main effects. One was that it committed Germany to an extended war on two fronts instead of the swift series of victories the nation’s planners had hoped. Secondly, Moltke was replaced for his failure; General Erich von Falkenhayn took his place as Chief of Staff.

The First Battle of the Aisne

The Allies saw an opportunity in the German failure. Until then, they had been fighting a defensive war. Maybe it was time to strike back.

The French Commander-in-Chief, Marshal Joseph Joffre, was keen to outflank the Germans. Their swift advance followed by retreat had left the German right flank exposed. If the Allies could get around it, they could inflict the crushing defeat the Germans had aimed for.

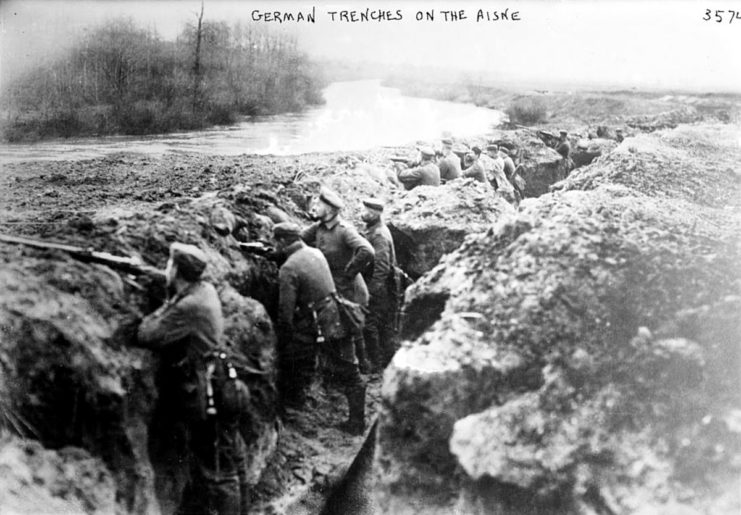

The Allies tried to do just that during the First Battle of the Aisne, fought in mid-September. French and British troops crossed the River Aisne and attacked the Germans. A shortage of heavy weapons hampered their attack. They were unable to push the Germans back and begin to outflank their forces.

With neither side able to shift the other, the fighting on the Aisne turned into a bloody stalemate. Soldiers on both sides began digging trenches, setting the tone for the rest of the war.

Fighting North

The fighting on the Aisne was only the first in a series of flanking maneuvers. Over the following month, both sides tried to get around each other’s flanks. They moved more troops north then attacked east or west, hoping to break through and encircle their opponents. Both sides were thwarted in their aims.

Fierce fighting took place in Picardy between September 22 and 26 and in Artois from the 27th until October 10. From there, both sides continued further north into Flanders, where they fought a series of bloody battles. The result was not a breakthrough. It was a stalemate.

The Allies were trying to move east, and the Germans were trying to move west. The result was that both armies moved north, following an almost straight line from the Aisne to the coast and the Straits of Dover. It was this retrospective appearance of a rush north that earned the fighting its label of the Race to the Sea.

The Fall of Antwerp

The effect of the Race to the Sea was the formation of defensive lines facing each other across northern France and the western tip of Belgium. The lines were completed, and the race brought to a halt by another piece of fighting – the attack on Antwerp.

From the start of the war, the Belgian government had intended to use the city of Antwerp as its last bastion. Surrounded by strong concrete fortifications, they thought they could hold out until their allies arrived.

They had not counted on the power of German artillery. After beating all the other Belgian defenses, the Germans laid siege to Antwerp on August 28. The arrival of British forces was not enough to save the Belgian city. In early October, the defenders withdrew. The city surrendered on the 10th.

The troops withdrawing from Belgium formed the final part of the line from the Aisne Valley to the English Channel. They took up defensive positions between Boesinghe and Nieuport, using the Yser Canal. It put them in line with the Allied troops advancing north. The forces joined up, completing the Race to the Sea.

Last Attacks

The Germans were not ready to give up on their flanking plan. During the second half of October, two important actions took place.

One was the formation of the Ypres salient. That territory, around 20 miles from the coast, was held by Allied forces despite the presence of Germans to the north and south. It was defined by the indecisive fighting in October. Although no-one knew it at the time, it was also the site of some of the heaviest fighting later in the war.

Meanwhile, the Germans launched an attack which became the Battle of the Yser. They tried to overrun the Allied defensive positions along the canal, breaking their enemy’s anchoring point against the sea.

The Belgians responded by opening the sluice gates of their irrigation systems, flooding the low-lying area. The region east of the Yser line became impassable to troops.

Digging In

The Race to the Sea was over. Each side now held a complete defensive line from the Swiss border to the sea. There could be no flanking maneuvers.

The war of movement was over. The war of attrition was about to begin.