During the First World War, both sides suffered horrifying numbers of casualties. War on an industrial scale left hundreds of thousands of men in desperate need of medical attention.

Transporting casualties to medical facilities became a huge issue. To get around this, the British government found an alternative – bringing the medical facilities to them.

So the ambulance trains were born.

Hospitals on Rails

In 1912, with war looming on the horizon, the British government began making preparations. They created the Railway Executive Committee to ensure the smooth running of the railway system during the war.

The Committee came up with plans to build 12 ambulance trains, which would move casualties around once they got back to Britain. By the time the war started, these plans had been sent in secret to the rail companies, who put them into action.

With patriotic fervor sweeping the nation, these companies went into overdrive preparing the trains. For industrial laborers and engineers far from the front, this was their chance to contribute to the war, and they completed the work with incredible speed.

The results were whole hospitals on wheels. They had operating rooms, wards, pharmacies, accommodation for staff, and even kitchens.

Once the war started, it became clear that the hospital trains wouldn’t just be needed in Britain. They were also sent to France, where they provided medical support close to the front lines and a vital link in the military medical system.

A Casualty’s Journey

The war’s casualties varied hugely. Some had been shot or stabbed. Others were the victims of poison gases that burned the lungs and blistered the skin. Many others came down with diseases in the cramped, exposed, and unhygienic conditions of the trenches.

The first step in a casualty’s journey was to get away from the front lines. If he couldn’t walk then he would be carried by stretcher bearers. During heavy fighting, some men lay for days in agony in no man’s land before they were rescued.

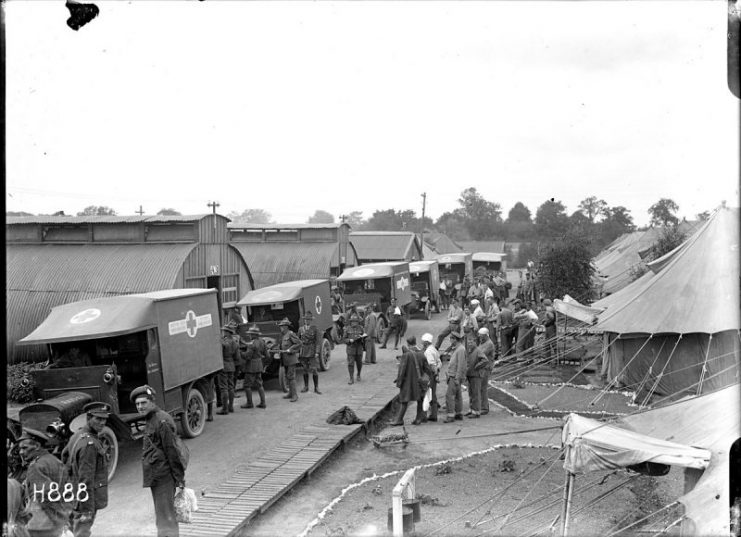

At Regimental Aid Posts and Advanced Dressing Stations near the front lines, the men received basic treatment. This included determining whether they were likely to survive long enough to justify ongoing treatment. If so, they were transferred onto the Continental Ambulance Trains, where they were treated and transported to a Casualty Clearing Station.

Away from the combat zone, the Continental Ambulance Trains transferred men between Clearing Stations, Base Hospitals, and evacuation ports, from which they were sent back to Britain. Along the way, the trains’ medical staff saw to their wounds and tried to make the journey comfortable.

For those being evacuated home, hospital ships provided the next leg of their voyage. These converted passenger liners carried medical staff and facilities, just like the trains. They risked being torpedoed by enemy submarines as they crossed from France to Britain.

Back in Britain, men were transferred onto the Home Ambulance Trains. These carried them to hospitals across the country for long-term care, from which they were eventually sent to convalescent homes or discharged, some of them returning to the war.

Life on the Trains: Soldiers

For many men, time on a hospital train was a grueling ordeal. Suffering from serious physical or mental injuries, their minds were consumed by their suffering. When many men were hurried on board after a major battle, they might get only the most basic treatment before the train set out. Then the train jolted into movement, unsettling broken bones and hastily wrapped wounds, while overstretched staff struggled to provide medical attention.

For other casualties, the trains could be something of a relief. Away from the horrors of the Western Front, they were supplied with beds, food, and medical care, in place of the mud and carnage. They found themselves in the company of men from all over the world, British and French troops lying side by side with Indians, Australians, Canadians, New Zealanders, Americans, and even captured German casualties. Animosities were set aside as they shared their suffering.

Crowded full of men, any train was soon filthy, smelly, and cramped. Only compared with the horrors of the war could they seem like luxury.

Life on the Trains: Staff

An average train was staffed by three medical officers, three nurses, 47 orderlies, and three chefs. Between them, they were responsible for the care of 500 passengers.

These staff lived on board their trains. This meant cramped conditions, though some were relatively comfortable, with baths and steam heating. Others had only the most basic of amenities, suffering through the cold with their patients.

As each soldier boarded the train, a medical officer checked their wounds and decided on their treatment. These officers and the nurses provided most of the medical attention. Orderlies changed dressings, fed casualties, brought water, and kept the place clean and tidy.

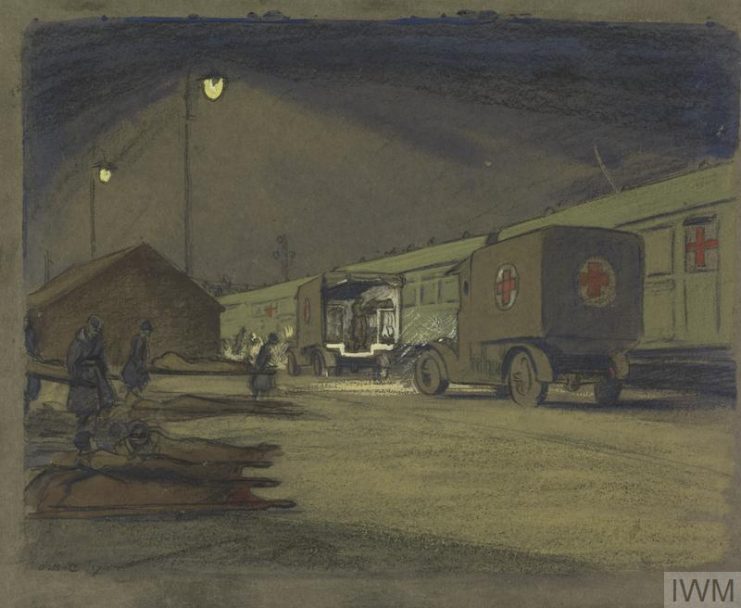

Working on the ambulance trains involved incredible effort. Staff worked day and night treating their patients’ wounds and trying to make them comfortable. They lived a life of strict military discipline. Even once the patients were unloaded, nobody rested until the train was cleaned and beds made.

It was dangerous work, too. The trains were close to the fighting front and used the same railways that transported weapons and ammunition. They risked being bombed as the Germans sought to cripple Allied infrastructure.

There were also the risks inherent to working in a hospital. In the cramped conditions of the train, doctors and nurses were vulnerable to catching their patients’ diseases or even their lice. Seeing the horrifying injuries of their patients wore at hearts and minds.

The breaks between journeys, which lasted days or even weeks, were incredibly valuable. For these brief moments, ambulance train staff lived something like normal lives, socializing and exploring new places, recovering their physical and mental energy.

All too soon, though, it was back on board and off to fetch the next batch of casualties. The war didn’t let up, and so neither could they.