A mystic, a savage sadist, a madman or one of the last cavalry strategic geniuses? This peculiar warlord left an interesting trace in Asian history. Baron Roman Ungern von Sternberg was a non-aligned, but anti-Bolshevik general during the Russian Civil War that occurred immediately after the revolution in 1917 and lasted until 1922.

The Civil War divided the nation, but while the Bolsheviks represented a united front, the “White Russians” couldn’t completely agree on the distribution of power among their ranks. When the supreme command over the royalist troops was given to Admiral Kolchak, Ungern von Sternberg refused to follow and continued to wage his own war in the wastelands of Mongolia.

Roman Ungern von Sternberg was born in Austria to a noble Baltic German family. The Baltic Germans lived in the territories of today’s Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia which was then part of the Russian Empire. He spent his childhood in Tallinn and was educated at the Marine Officers Cadet School in Saint Petersburg.

During the brief Russo-Japanese conflict, von Sternberg volunteered to for the front but arrived too late to participate in combat. Nevertheless, this adventure sparked his fascination with the wonders of the Far East. He would develop this fascination in the following year while serving in Siberia among the Amursky Cossacks where he was introduced to the nomadic lifestyle of the Mongols and Buryats.

During the First World War, von Sternberg was at the frontline, commanding his Cossack cavalry against the Austro-Hungarians in Galicia. He became famous for his rear-action raids with the Cavalry Special Task Force. Von Sternberg gained an ambivalent reputation ― there was no doubt in his bravery, but many wondered about his sanity.

During the February Revolution in 1917, which was a prelude to the October Revolution, the Baron was transferred to the Caucasus where befriended Grigory Semyonov, a Russian officer who was in charge of organizing Assyrian Christians in a struggle against the Ottoman Turks who were fighting on behalf of the Central Powers.

When the civil war broke out most of the Baltic Germans nobility aligned with the anti-Bolshevik coalition including Baron Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel who was one of the leading figures of the White movement. Roman Ungern von Sternberg had at that point already developed his political views in which he expressed admiration of the monarchy.

He and Semyonov immediately declared their allegiance for the Tsar and started to combat the revolutionaries. In the meantime, Semyonov gained sponsorship from the Japanese Government and the two began to lead their own counter-revolution, outside of the White Russian movement, which in that time gathered most of the Army elite. The Whites saw this as an act of treason and ended all relationships with Semyonov and Ungern von Sternberg.

Ungern von Sternberg was soon after dubbed the “Mad Baron” due to his eccentric and often violent behaviour. Semyonov and Ungern von Sternberg fought the Bolsheviks in the Baikal Lake area in Central Asia. Semyonov entrusted the Baron with guarding the Dauria railway station which was of great strategic importance.

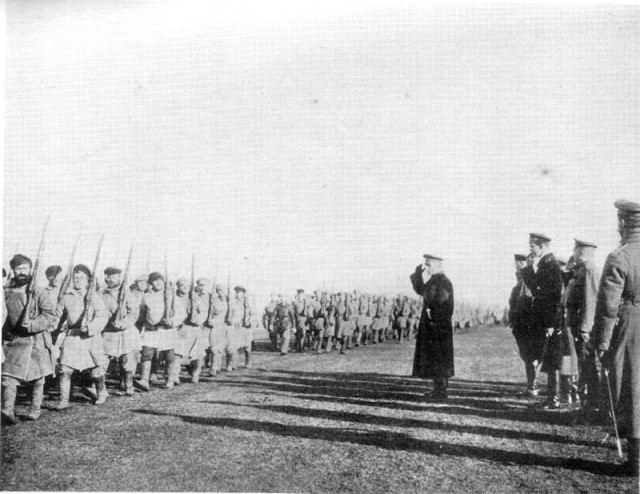

Von Sternberg organized an Asiatic Cavalry division – a cruel and savage force which controlled the vast Trans-Baikal region with an iron fist.

The Division consisted of many nationalities ― Russians, Buryats, Tatars, Bashkirs, Mongols of various tribes, Chinese, Manchu, Japanese and Polish exiles. They were dubbed “The Savage Division”, a name earlier used by the Russian Imperial Army to classify the units consisted of mountain peoples, mostly from the Caucasus. Ungern von Sternberg plundered and robbed trains that passed through the area under his control, to gain resources for his war effort.

He began to pursue his idea of establishing a Mongol Empire with the help of Bogd Khan, the Mongol spiritual leader. At this time, the Baron was heavily involved in studies of Vajrayana Buddhism and other religious sects of the Far East.

His plan wasn’t just to revive the Mongol Empire, but to re-establish monarchies all over the world, as his hate towards Bolshevism grew to an incredible extent. Von Sternberg began planning his expedition into Mongolia in 1919, which was held by Japanese-backed Chinese warlords. Also, part of his plan was to marry a Manchurian princess Ji, thus gaining influence among the Chinese aristocracy.

The political aim of the marriage was to get close to General Zhang Kiuwu, who controlled the Chinese-Manchurian Railway. The railways represented the most important lifeline in Syberia and the Far East. Much of the regions economic resources was in the hands of those who controlled them. In order to attack the Chinese, who had Japanese support, von Sternberg ended his cooperation with Semyonov even though the two remained friends.

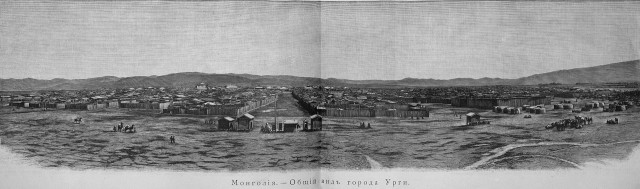

When everything was set, he tried to charge the Mongol capital, the city of Urga (now Ulan Bator) but suffered initial a defeat from the Chinese. In the meantime, he gathered support from the Mongols seeking independence under Bogd Khan, whose influence grew following the invasion. Was it bravery, or madness, or perhaps both that fueled the Baron’s conquest, for his division was 1460 strong and the Chinese garrison numbered 7,000 soldiers who fought the horsemen with machine guns and artillery.

In February 1920, one of von Sternberg’s commanders, Rezukhin, managed to break through the Chinese lines and wreck havoc among the enemy troops. They had captured parts of the city of Urga and liberated a spiritual leader called Bogd Gegeen, which gave his troops a large morale boost.

After this event, the Baron ordered the troops to rest. Reinforcements were arriving just while the Rezukhin detachment held positions within the city. Using an old Genghis Khan tactic, von Sternberg gave orders that numerous campfires be lit in the field just outside the city, by the reinforcements. This gave a fearful impression of an overwhelming force, surrounding the city, even though the Chinese had superior numbers.

In the next few days, major assaults were conducted, driving the Chinese out of Urga. The remaining Chinese tried to re-organize and conduct a counter-attack, after being driven out of Urga, for they still had several thousand troops in Mongolia. They were met by a few hundred Mongols and Cossacks who fought them fiercely from March 30th to April 2nd. The Chinese were eventually routed and retreated beyond the southern borders of Mongolia.

Bogd Khan was restored to the throne in February 1921, in a solemn ceremony. As a reward for ousting the Chinese out of Mongolia, Bogd Khan granted Ungern fon Sternberg a hereditary high title darkhan khoshoi chin wang in the degree of khan.

Mongolia was declared an independent monarchy under the spiritual rule of Bogd Khan with Ungern von Sternberg as its de facto dictator. Roman Ungern von Sternberg further developed his streak of mysticism, later, proclaiming himself the reincarnation of Genghis Khan. His philosophy was a mixture of Buddhist mysticism and Russian nationalism. In the eyes of his soldiers, he was a godlike creature who would lead them to countless victories. They called him the “God of War”.

He established a Tibetan colony in Urga and had good relations with the 13th Dalai Lama who supplied him with warriors. Roman Ungern von Sternberg was also a notorious anti-Semite who was personally responsible for the execution of more than 800 Jews within the Mongol region.

He immediately expressed imperialistic tendencies and started a small campaign in the border areas between Mongolia and Russia. His army numbered about 3,000 horsemen. The Bolsheviks had already won the civil war and were amassing their troops to crush the new-formed Mongol Empire and establish a communist state.

The Mad Baron was outnumbered and outgunned. His medieval tactics and extensive cavalry use was no match for the Soviet artillery, armored cars and machine guns. His own troops started to rebel against him while he desperately tried to retreat to Tibet. Baron Roman Ungern von Sternberg was arrested on August 20th, 1921. A trial was held after which he was executed by a firing squad.

A historian, James Palmer, wrote in his book, The Bloody White Baron, published in 2008:

“When he learnt of his death, the Bogd Khan ordered prayers for his soul to be read throughout Mongolia. They were undoubtedly needed.”

All images from Wikipedia.