In August 1914, fighting broke out between Germany and Russia – it was the beginning of WWI on the Eastern Front. Russia declared war on Germany and then promptly invaded East Prussia.

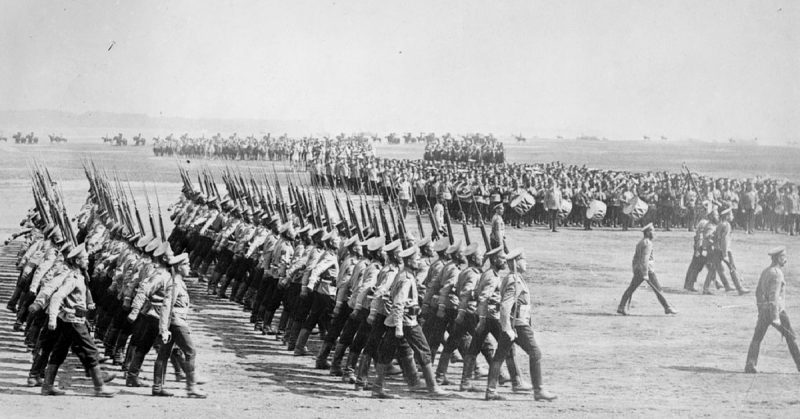

Mobilizing for War

Until 1909, Russia had been relatively slow in its ability to mobilize for war. Then General Vladimir Sukhomlinov began extensive reforms of the nation’s military as rail networks were expanded to allow faster mobilization.

German war plans relied on a slow Russian mobilization. Aware that things were changing in Russia, their plans had been modified to put more troops on their eastern border. The bulk of the German forces still went west.

However, the speed with which Russia gathered its armies and brought them to the border surprised almost everyone. The Tsar signed the mobilization orders on July 30. The process started on August 4. By the 15th, nearly all the troops were in position.

Constrained by Geography

The Russian plan was to invade German East Prussia. It would draw off German resources, preventing the Germans from winning a quick war in the west and then turning their attention east.

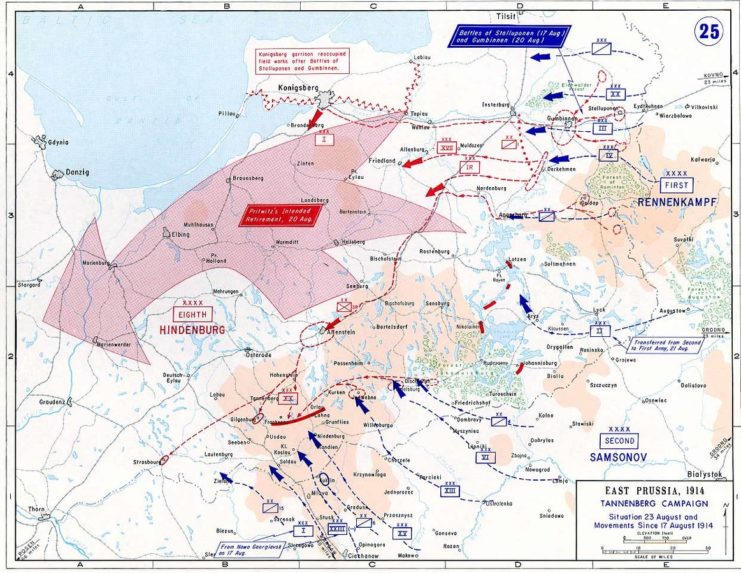

Geography limited the way that Russia could go about it. Strong fortifications around Königsberg and Torún could not be bypassed and would take a lot of effort to beat. They obstructed an advance in the north or southwest. In the center, the Masurian Lakes and the fortifications between them provided another obstacle. The Russians were left with two possible routes of attack – from the east or the southeast.

They decided to advance along both routes, despite the difficulties in coordinating between two completely separated armies.

Pincer Movement

The Army advancing from the east was commanded by General Paul von Rennenkampf, while that from the southeast by General Alexander Samsonov. Between them, they had 29 divisions. Against them stood General Maximilian von Prittwitz commanding 13 divisions. Although the Russians had superior numbers, they were ill-equipped and supplied.

Rennenkampf advanced first on August 15, aiming to draw Prittwitz out. Two days later, Samsonov began his advance. Their plan was to catch Prittwitz’s forces between their two armies, trapping the Germans in a pincer movement.

Early Successes

Things began well for the Russians.

On August 17, Rennenkampf’s forces defeated a German raid at Stallupönen. On the 20th, a far larger attack hit them at Gumbinnen. Again, they fought off the Germans.

Morale rose among the Russians.

Prittwitz was in a panic. Without permission from his superiors, he ordered his troops to retreat to the River Vistula, abandoning most of East Prussia.

Germany Regroups

The German high command quickly countermanded Prittwitz’s orders. They replaced him on the 23rd with General Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy General Erich Ludendorff.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff adopted a plan developed by General Max Hoffmann, the chief of operations of their new army. It was a bold strategy to deal with the Russian forces one at a time.

Rennenkampf had slowed his advance almost to a halt. The Germans left a cavalry screen facing him, then hastily redeployed their four corps.

One corps raced by train to a position on Samsonov’s left flank. Two marched south to places on his right flank. The fourth stayed near the village of Tannenberg, which sat in the way of Samsonov’s advance.

With all their forces redeployed to face Samsonov, they were ready to take him on.

The Battle of Tannenberg

On August 26, the Germans began attacking Samsonov’s exposed flanks. Over the next three days, his isolated force came under relentless German attack. It not only halted his advance but shattered his army.

The Battle of Tannenberg was an overwhelming victory for the Germans. They killed, injured, or captured more than half of the 230,000 Russians. They lost 20,000 men.

The victory at Tannenberg was widely celebrated in Germany. It provided a morale-boosting victory after early failures in the east and growing complications in the west. Hindenburg and Ludendorff became popular heroes.

Samsonov committed suicide in the forest.

The First Battle of the Masurian Lakes

Tannenberg had been a defensive operation for the Germans, using Samsonov’s advance against him. Next, they went on the offensive to tackle Rennenkampf. German soldiers were diverted from the Western Front, contributing to the stalling of the Schlieffen Plan to defeat France.

Rennekampf was pushing deeper into East Prussia. On September 7, the Germans attacked his forces in their right flank. Once again the Germans used the exposure created by the Russian advances, against them. It was the beginning of the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes. The attack sliced through the German forces south of the lakes, and it was only through a hasty retreat that Rennenkampf avoided getting caught in a trap.

The Battle of the Niemen

By September 13, the roles had been reversed. Hindenburg was invading Russia, while Rennenkampf was pulling back to a safe position behind the River Niemen.

The state of the armies also altered. The Russians, who had been struggling with supplies and lost troops, could access supplies inside their own territory and were reinforced by the Tenth Army. Meanwhile, the Germans were running out of supplies and becoming tired from their advances.

On the 25th, Rennenkampf launched a counter-attack – the Battle of the Niemen. Three days of fierce fighting halted the German advance.

Heavy Losses for Little Change

At the end of two invasions and over a month of fighting, the strategic situation was back to where it had started. Regarding territory and position, almost nothing had changed.

However, the human cost had been high. The Germans had suffered 100,000 casualties, the Russians 125,000. Nearly a quarter of a million men were dead, wounded, or missing – for nothing.

And the war had only just begun.

Source:

Ian Westwell (2008), World War I