Lieutenant George: Great Scott sir, you mean, you mean the moment’s finally arrived for us to give Harry Hun a darned good British style thrashing, six of the best, trousers down?

Captain Blackadder: If you mean, “Are we all going to get killed?” Yes. Clearly, Field Marshal Haig is about to make yet another gargantuan effort to move his drinks cabinet six inches closer to Berlin.

– Richard Curtis and Ben Elton, Blackadder Goes Forth (1989)

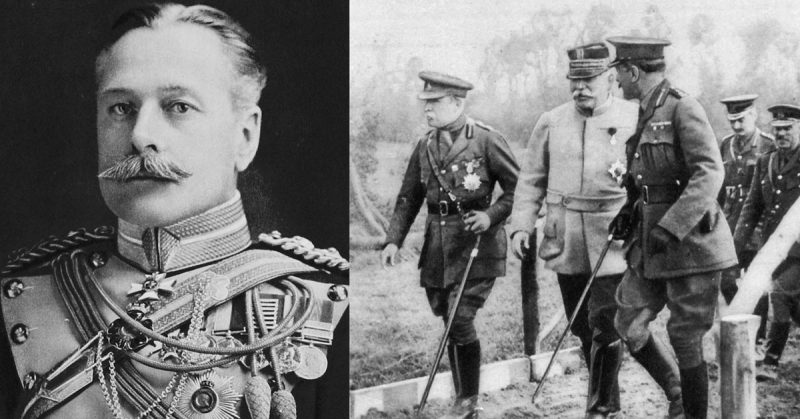

General Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British forces for most the First World War, is a figure of infamy among those concerned with the horrors of war. Under his command, hundreds of thousands of British soldiers died in attacks ill-suited to the conditions they faced.

What led Haig into this approach to war – and should he really be remembered with such disdain?

Origins of a Commander

Born in 1861, Haig’s career prior to the First World War combined traditional paths to power with a professionalism that was by no means necessary for promotion.

On the one hand, Haig’s career was supported by the patronage system that saw the British army’s officer corps filled not by the brightest but by the best connected. With a connection to the royal family through his sister, and the support of two knights and a lord, his upward trajectory was an easy one.

His role as a cavalry officer helped. The cavalry was traditionally the elite of the British army, disproportionately staffed by the upper classes, and so serving there gave Haig prestige and valuable contacts.

On the other hand, Haig had great potential as a commander and the ambition to make the most of his opportunities. Studies at Oxford and Sandhurst left him better educated than most officers, and he thought carefully about the military issues of the day.

A Nineteenth Century Model of War

Unfortunately, Haig’s education and cavalry background also limited his thinking, fitting it into a traditional Victorian mould. The Victorian aristocracy valued strength of character above intellect and showed little respect for the impact of science and technology in the military. Haig believed that moral character was the deciding factor in war, and that superior character would lead the better side to victory.

Believing in efficiency but also tradition, Haig assisted army reforms in 1906-9 while also limiting their impact. He supported the elitist social structure of command and the dominant place of cavalry. For him, war was about decisive battles taking place in three stages – wearing down enemy reserves, a rapid and decisive offensive, and exploitation of the results by cavalry. He believed infantry would not able to shoot straight when faced by the moral force of a cavalry charge.

Taking Over the BEF

By the outbreak of World War One, Haig had risen far enough to be given command of I Corps, reporting to the commander-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), his old mentor Sir John French. Despite their connection, Haig assisted in French’s removal from his post, and on 19 December 1915 Haig took command of the BEF.

Haig’s self-belief was absolute. He was certain that he, unlike other generals, knew the right way to fight the war. A staunch Christian in the British tradition, he believed himself to be God’s agent. How could he fail with God on his side?

These attitudes shaped Haig’s staff. He surrounded himself with uncritical supporters who fuelled his self-belief. His intelligence officer, Brigadier-General John Charteris, focused on gathering information to prove Haig right in his decisions, rather than to evaluate what was going on. Stern and obsessed with etiquette, Haig made it virtually impossible for anyone to challenge him, or to present him with ideas other than his own.

How Haig Fought

Haig’s approach to winning the war can seem contradictory to modern eyes. Though he never accepted that the Great War was a war of attrition, that was the way he fought it, trying to wear down enemy reserves and to achieve a breakthrough. His idea of victory was cavalry pouring through a gap in the enemy lines, opening up the swift war of movement he still thought was the way to win.

A strategic rather than a tactical commander, Haig took a hands-off approach to the details of fighting, giving his commanders space to make tactical decisions. He provided orders so vague they left room for others’ incompetence to flourish, as in his command to Gough at Passchendaele in July 1917 – “wear out the enemy but have an objective”. Haig’s apparently admirable focus on the big picture led him to overlook the reality of what was happening on the ground. Again, this was highlighted by Passchendaele, where he chose a battlefield that suited his strategic purpose of breaking through to the ports of Flanders, but where the enemy was well dug in on the high ground.

The Best Man for a Bad Job?

It has been argued that Haig was the best man for the terrible job of commanding the BEF through a gruelling war. Certainly his peers in the British army held many of the same misguided views, but without the education and strategic oversight to refine their work. Ultimately, the British won under his command, apparently vindicating him.

The war was won less through strategic brilliance than through Germany’s economic exhaustion. Even when the British saw victories in the last year of the war, this was primarily down to commanders on the ground, freed up to use their initiative by Haig’s hands off approach.

A more open minded commander might have adapted to the new style of warfare, saving hundreds of thousands of men from the meat grinder of relentless offensives. Was there such a man ready to lead the British army between 1914 and 1918?

We will never know.