Submarines were among the important new technologies that came to the fore during WWI. Although work on submarines had been underway for decades, it was the first time they were really influential. Technology had reached a point where hostile nations could deploy reliable fighting submarines.

German Submarines: The U-Boats

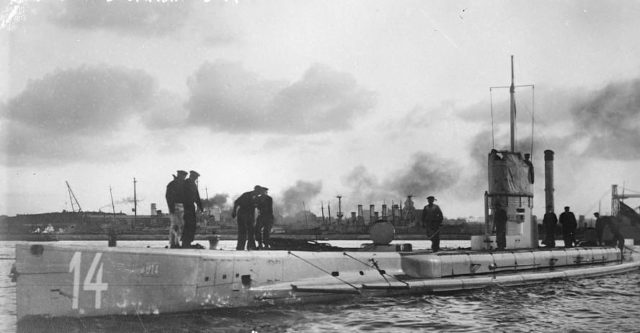

Germany led the way in submarine technology and production. Germany’s large, long-range submarines were known as U-boats, a term derived from the word Unterseeboot, meaning “submarine boat.” Two other classes of submarines, UB-boats, and UC-boats, were also used. They were smaller vessels and did not have as good a range. They were used mostly in coastal waters.

One of the most remarkable features of the German submarine force was its pace of growth. The first German submarine entered service in 1906. 30 were available when war broke out in 1914. By the end of the war, another 350 had been in service, with up to 61 at sea at any one time.

One of the best decisions made by the German manufacturers was to stick with a limited number of designs. Instead of varying the U-boats, they built large numbers following similar templates. They were easier to manufacture and simplified crew training.

The U and UB-boats were equipped with torpedoes and guns, and their role was to harass Allied shipping. The U-boats operated far out in the oceans as Germany tried to cut off Allied supply lines, and destroy their opponents’ ability to wage war.

The UC-boats were used to lay mines in the Baltic, Black Sea, English Channel, and Mediterranean. The first of them, UC-1, was itself probably sunk by a mine off the Belgian coast.

As well as combat vessels, the Germans experimented with using submarines to carry cargo. The first of its type, the Deutschland, sailed to the then-neutral USA in 1916 to trade for war materials. It was as much a propaganda mission as a practical one, proving what Germany could achieve. However, it was evident that U-boats were more valuable as combatants than as traders, and the ships were converted into fighting submarines.

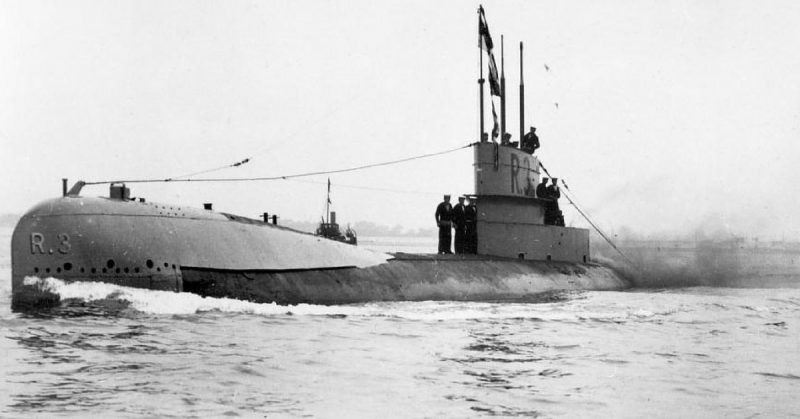

Allied Submarines

Although not as well equipped as the Germans, all the principal Allied nations at the start of the war had submarines. The French had 123, by far the largest group. The Russians had 41. The Italians had 25. The British had 57, but 40 of them were suitable only to serve around the coast.

Most of the Allied nations had problems with their submarines. The French submarines at the start of the war were old and unreliable. Most of the Italian boats were limited to short-range missions. The Russian vessels were outdated, and they relied on German engines to build more modern submarines – not an option when they were fighting the Germans.

None of those nations went in for building submarines to the same extent as the Germans although the British were close. They had 137 submarines by the end of the war, with 78 more under construction and 54 lost in action.

Some of the British submarines were sent to the Baltic to support the Russians. There, they attacked German vessels carrying Swedish ore, cutting down Germany’s vital war supplies. They also sank several warships. In March 1918, when Germany and Russia made peace, the Russians were to hand their submarines over to the Germans. Instead, their crews scuttled them.

British submarines also played a part in the Mediterranean, where they attacked Turkish supply, transport, and combat ships.

During the course of the war, the British tried a new type of submarine, the huge K-class boats. They were intended to serve alongside surface warships. However, they were slow to submerge and almost impossible to spot once they were underwater. Those drawbacks led to collisions and the accidental loss of five of the 17 K-class boats. They were never an effective weapon.

Anti-Submarine Weapons

In response to the new threat, steps were taken to develop anti-submarine weapons. The British took the lead, due to the threat to their shipping from U-boats.

The weapons ships already had were useful against surfaced submarines but could not hit them under water. New weapons were therefore required. Electronically detonated explosives called sweeps were dragged behind ships but needed to be very close to a submarine to be effective. Depth charges, bombs designed to explode underwater, were produced in 1915 and widely available from 1917.

The development of hydrophones, equipment to listen for submarine engines, allowed depth charges to be targeted better. But submarines could often avoid detection by remaining silent and deep in the ocean.

The introduction of convoys in April 1917 let ships protect each other and led to more U-boats being sunk. Before then, some ships towed submarines with a telephone connection behind them, so when a U-boat attacked the Allied submarine was ready to counter-attack.

More passive ways of fighting submarines were also developed. Q-ships were British vessels disguised as merchants but with hidden weapons, which lured surfaced U-boats into an ambush.

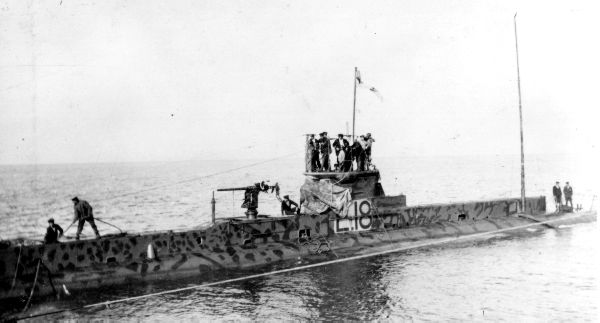

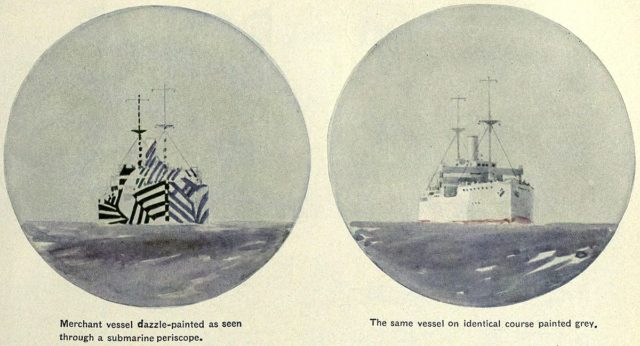

Zig-zag sailing patterns and camouflage paint helped ships to survive sailing through submarine-infested waters.

Anti-Submarine Barriers

The Allies used barriers known as barrages to prevent German submarines from getting to their ports. The three largest barrages were in the English Channel; between Norway and the Orkney Islands in the North Sea, and in the Strait of Otranto.

The barrages consisted of mines, nets, and surface boats. The nets were designed to be dragged along by any submarine that got caught in them. A submarine would either have to surface to get rid of the net or drag it around identifying its presence. Either way, it made a U-boat visible and so vulnerable to attack.

The barrages helped to limit German activity, at one point denying access to U-boats in the English Channel for 12 months. Ultimately, it was the convoy system that took a real toll on the German submariners, although U-boats remained the most powerful submarine force right up to the war’s end.

Source:

Ian Westwell (2008), World War I