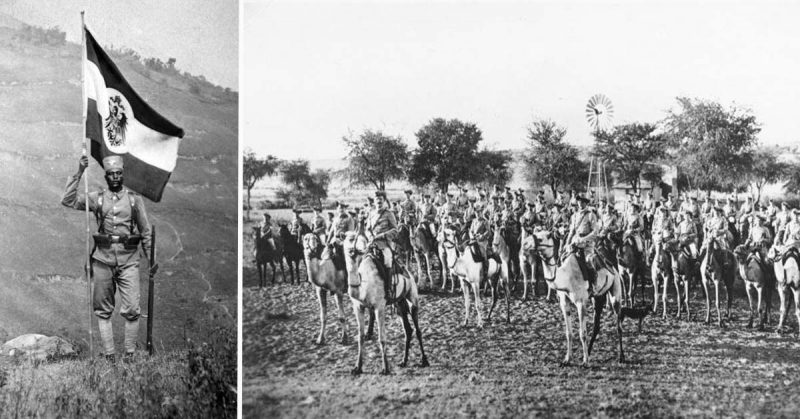

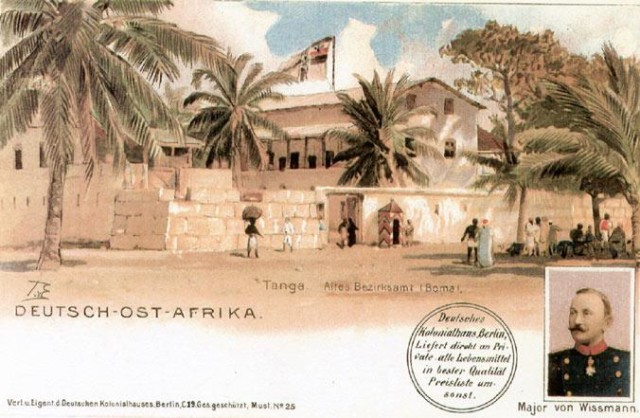

In the sweltering heat of East Africa, the British received one of their first defeats of World War One. The attempt to seize the port of Tanga from the Germans was a humiliating disaster, and one the British brought on themselves.

Major-General Aitken

The Tanga expedition – Britain’s planned 1914 campaign against the Germans in East Africa – was regarded by the British government as a minor affair into which they should not put good resources that could be used elsewhere. This was reflected in the quality of both the troops and their commander.

Major-General Aitken was an officer in the colonial tradition. 35 years in India had left him hugely confident both in himself and in Indian troops. Such was his over-confidence that he refused to listen to the advice of others, including those with knowledge of the region he was being sent to.

Aitken’s support for Indian soldiers should not be misunderstood as reflecting an enlightened attitude on race or nationality. One of his reasons for confidence was the disdain in which he held the “Huns” and “Blacks” he expected to face.

Poor Troops

Aitken’s confidence in his troops was sadly misplaced. He had two groups of high-quality troops – the Gurkhas and the North Lancashire Regiment. The rest of his 8,000 soldiers were among the worst trained in the Indian Army. They had only just been issued Lee-Enfield rifles and lacked skills or experience with these modern weapons. Even communication was difficult – they had been recruited from so wide an area that they spoke twelve different languages.

It would be hard to create high-quality troops with poor leadership, and the British officers must take much of the blame for what followed. Some had never set eyes on their troops before embarking for Africa. Captain Meinertzhagen, the expedition’s Intelligence Officer, said that “the senior officers are nearer to fossils than active energetic leaders”.

A Dreadful Journey

The ocean voyage to Africa did much to weaken the troops. Delays meant they spent an extra sixteen days in hot, cramped quarters. No thought was given to dietary needs, including those stemming from religion, and many came down with diarrhoea from unfamiliar food. Others suffered seasickness.

When they finally reached Mombasa, Aitken refused to give them time ashore to recover before heading to Tanga.

Giving the Game Away

The supposedly secret expedition was poorly hidden. Crate labels on the Bombay docks announced their destination to the world. Press reports and un-coded radio messages told the Germans that trouble was coming. The fleet even sailed down the African coast in sight of land, letting the Germans know they had arrived.

How Not to Land an Army

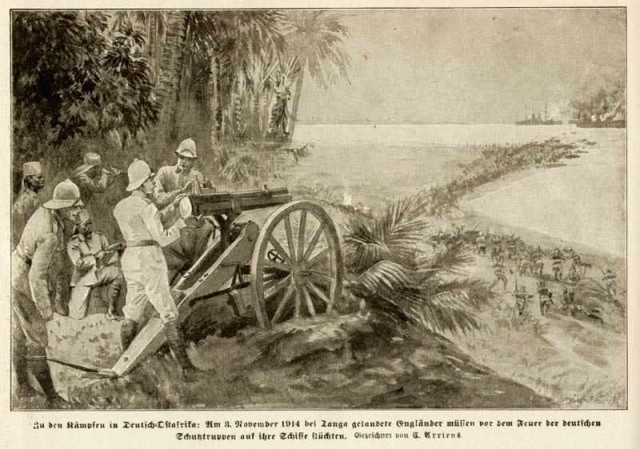

Any remaining surprise was ruined when the cruiser HMS Fox arrived in Tanga ahead of the expedition. Captain Cauldfield went ashore to cancel truces with the Germans. He asked Von Schnee, the local commissioner, if the harbour was mined, and believed Von Schnee when he answered yes.

The British delayed landing while they failed to find the non-existent mines in the harbour, then decided to instead land a mile from town in a swamp. Men and supplies were offloaded into a miserable morass full of mosquitoes, leeches and snakes.

“2500 Germans”

Having given the Germans two days to prepare, Aitken ordered an advance on Tanga. Ambushed by hidden troops, the 13th Rajputs turned and ran, leaving a dozen officers to be killed. Meinertzhagen tried to stop the panic, only for an Indian officer to threaten him with a sword.

Brigadier Tighe of the Bangalore Brigade informed Aitken that they had been held up by 2,500 German soldiers. In fact, the whole advance had been routed by 250 local troops.

A Strong Defence

Meanwhile, Tanga’s defenders had made good use of their time. Strong defensive positions with barbed wire and machine guns blocked the British advance. German emplacements were connected by telephone. Snipers sat in the trees, shooting down at the heads of the invading soldiers.

Covered in Bees

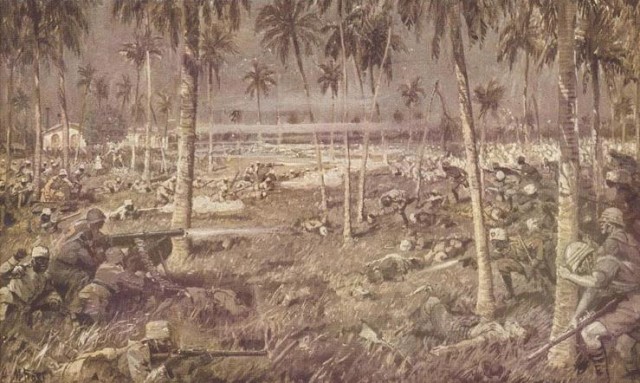

Despite German preparations, the Gurkhas and North Lancashires made strong advances, seizing Tanga’s hospital and customs house. But the other attacking troops were having an increasingly miserable time. Bullets whistled down around men who could not see the way forward through eight-foot fields of corn. Water rations had been exhausted as they advanced in the heat.

Now nature itself would turn upon the Indian troops.

The advance took them beneath hanging hives made out of hollow logs. The sounds of shouting and gunfire agitated the occupants of these hives – swarms of large, aggressive African bees. Clouds of them poured out and descended on the soldiers, many of whom panicked and fled, believing this was a German trick. Some ran into the sea to try to avoid being stung. Others ran back along their line of advance, surrounded by swarms of bees. One man was stung 300 times.

The defenders suffered some attacks from the bees, but nothing like what the British suffered.

The Wrong Bombardment

Aitken had refused to bombard Tanga in preparation for the assault, partly for fear of harming property in a town he planned to occupy, partly because he didn’t know where the German troops were. Seeing his men in full retreat, he changed his mind.

Most of the shells from the British bombardment fell upon the retreating friendly troops. Only one other hit of note was recorded – against Tanga hospital, now occupied by British soldiers and their own wounded.

Meanwhile, untrained soldiers were firing wildly, hitting as many of their comrades as of the enemy.

A Costly Retreat

With 800 men dead, 500 wounded and 250 missing, Aitken gave in and re-embarked his troops onto the ships. He did this so promptly that they left their supplies behind. The Germans, who had lost only 69 men dead or wounded, gained enough rifles, machine guns and other equipment to raise new regiments.

Aitken’s expedition was a disaster. On his return to England, he was demoted to colonel and forced into retirement.