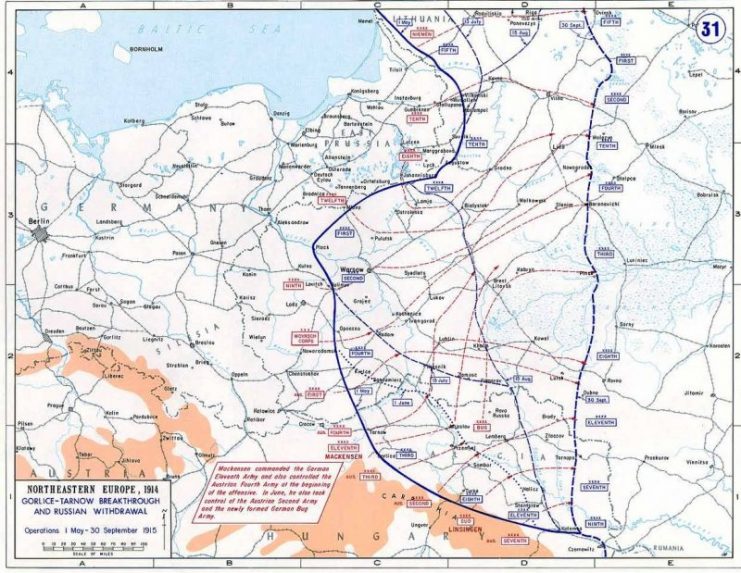

1915 saw some of Germany’s greatest successes of the First World War, and all on the Eastern Front. In the Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive and related smaller operations, German armies pushed the Russians back hundreds of miles, taking over a million prisoners and proving that the war in the east need not be the static mess of siege lines it had become in the west.

The Eastern Front

The Eastern Front had seen mixed fortunes for the Central Powers in 1914. Russia had launched major offensives into Poland, Galicia, and East Prussia. The Germans, initially stunned by the speed and ferocity of the Russian attack, regrouped and smashed the armies that had moved against them. But further south, Austro-Hungarian forces were swept aside by the Russians, and the whole front threatened to collapse.

The Germans were forced to move more troops east to bolster their Austro-Hungarian allies and hold the Russians at bay. They even managed to retake some of the lost territory before the end of 1914.

The winter offensive of early 1915 brought a similar pattern. The Germans drove the Russians back in the north, taking parts of Poland. But in the Carpathian Mountains to the south, Austria-Hungary took terrible casualties and achieved little in return.

It was increasingly clear that the Germans would have to shore up the demoralized and divided forces of their allies. A great success was needed to drive the Russians back.

The Kurland Diversion

Preparation for the Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive began in earnest in April. General von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of Staff, relocated to Pless in East Prussia to oversee the offensive. He also authorized the release of soldiers from the Western Front for this attack.

The operation began on the 26th of April with a diversionary attack into Kurland, a plain on the Baltic coast. A small German army advanced on Libau, drawing growing numbers of Russians away from the real targets.

As successes took place on other parts of the front, the Kurland offensive was extended over the summer. Kovno fell in mid-August and the city of Vilna was taken on the 26th of September.

Targets and Forces

While Kurland would prove a success in its own right, German attention was focused further south.

The main targets were Russian Poland and the territory of Galicia, captured from the Austro-Hungarians by the Russians earlier in the war. Poland had often been fought over by forces from Germany and Russia, and once again the city of Warsaw became the target for armies on the march. The recovery of Galicia was a chance to regain some dignity for the beleaguered Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was increasingly propped up by the superior military strength of the Germans.

The plan called for a two-pronged advance. The German Twelfth Army, led by General Max von Gallwitz, formed the northern prong, heading south-east into a Russian-occupied salient, towards Warsaw. Meanwhile, the Eleventh Army would advance further south, from a starting point between Gorlice and Tarnów. This army consisted of 120,000 men drawn from the Western Front, led by General August von Mackensen.

Fall of the Third Army

The main offensive was launched on the 2nd of May. The Eleventh Army advanced along a front nearly 30 miles wide, straight through the northern flank of the Russian Third Army. This Russian army was already weakened by earlier fighting, and now it trembled before the might of the German advance.

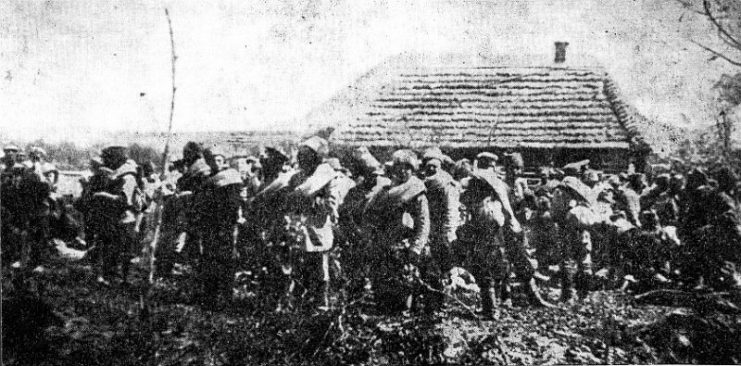

By the 10th of May, the Third Army was in ruins. 200,000 men had been lost, 140,000 of them taken prisoner by the advancing Germans. The remnants were given permission to withdraw to the River San, but it was too late to save anything worth having. The army had effectively been destroyed.

Despite the shock they had received, the Russians were not willing to roll over and accept defeat. On the 19th of May, they began a series of counter-attacks against the Eleventh Army. But the Germans kept coming, and the last of the counter-attacks ended on the 25th.

On the 4th of June, the Germans captured Przemyśl. Galicia was falling, and there was nothing the Russians could do to save it. They began evacuating on the 22nd, two days before Lemberg fell.

Towards the end of June, the Germans wound down the southern prong of the attack. They had suffered around 90,000 casualties. In return, they had retaken Galicia and captured 250,000 Russians, leaving many more dead in the field.

Taking Poland

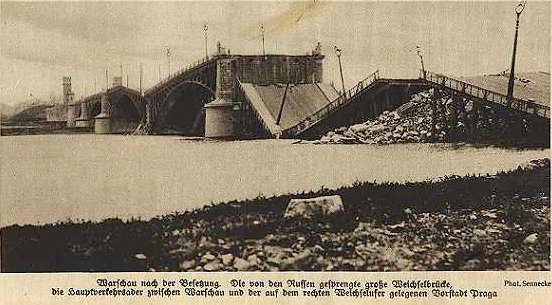

It was a similar story in the north. The Twelfth Army advanced across Poland, driving back the Russians standing before it. Warsaw was taken in early August, Brest-Litovsk on the 25th, and Grodno on the 2nd of September.

Rather than risk being cut off, the Russians pulled back, taking as much war material with them as they could. This operation, known as the Great Retreat of 1915, salvaged something from the disaster. But there was no avoiding that it had been a disaster.

The Power of Artillery

The German armies had already proven their superiority to the Russians, but what brought them such staggering success in 1915?

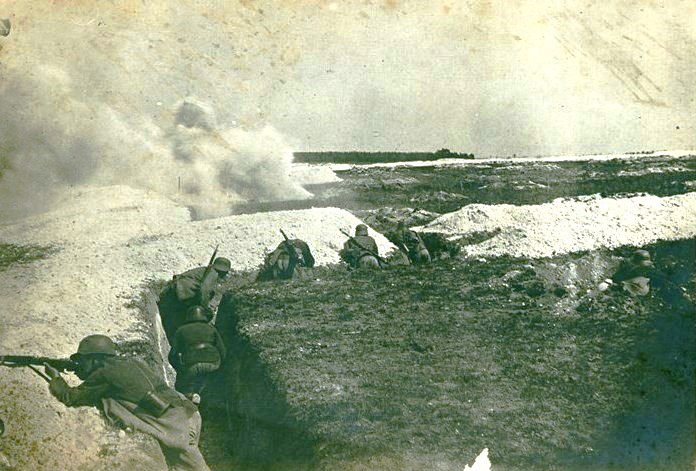

The most important factor was artillery. Since the mid-19th century, Germany had had a well-deserved reputation for the quality of its armaments industry. During the Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive, this gave it vastly superior firepower.

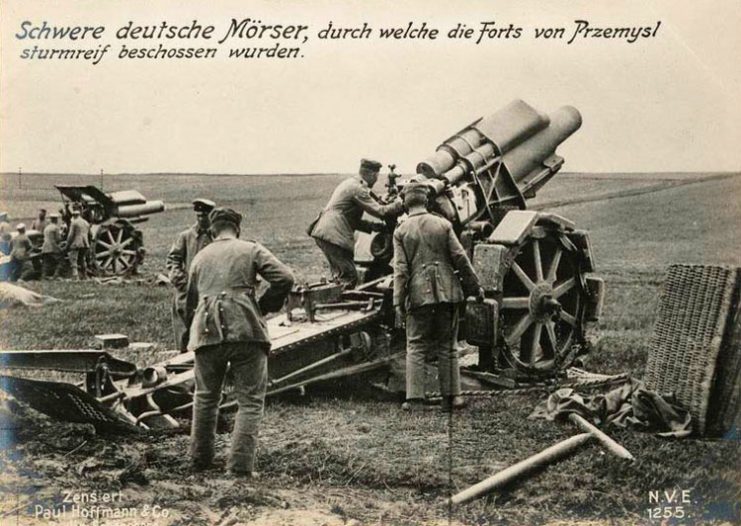

Siege mortars smashed fortresses. Light artillery supported infantry advances. Howitzers and heavy field guns ripped apart the Russian counter-attacks and destroyed the enemy batteries. Aerial observation improved the accuracy of this fire. In both technology and technique, the Germans had the artillery edge.

Measures of Success

The 1915 offensives were a huge success for the Germans. In places, they pushed the Russians back 300 miles. A new front line was established, giving the Central Powers control of Poland and Galicia. The Germans suffered 250,000 casualties and the Austro-Hungarians 715,000, but the Russian suffered a staggering 2.5 million casualties, a million of them taken prisoner.

The Western Front might have been a stalled quagmire, but in the east, the Germans were on the march, one in a series of steps that would eventually knock Russia out of the war.