In any military conflicts, the opposing sides are looking for new means and methods to defeat the enemy. After the invention of blasting explosives, several extremely large explosions occurred, some of which were accidents. Below are two of the most powerful explosions of the First World War.

Halifax Explosion

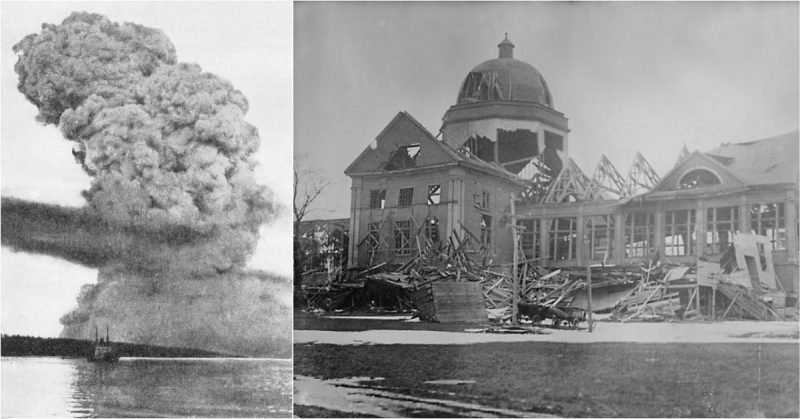

The explosion in Halifax, Canada, is one of the strongest explosions of the pre-nuclear age. The explosion occurred on December 6, 1917, in the harbor of the city of Halifax. The French cargo ship SS Mont-Blanc, loaded with a large amount of explosives, collided with the Norwegian ship SS Imo.

After the collision, a fire broke out, which subsequently led to a strong explosion, numerous casualties, and great destruction.

On November 25, 1917, Mont Blanc was being loaded in the port of New York with 200 tons of TNT, 2,300 tons of liquid and dry picric acid, 10 tons of pyroxylin, and 35 tons of benzol.

After loading, the ship headed for Bordeaux, but through an intermediate point at Halifax. The plan was to form a convoy to cross the Atlantic.

On the morning of December 6, Mont-Blanc arrived at Halifax. At the same time, the Norwegian ship Imo was leaving the port.

As the two vessels approached each other, both captains began to make risky maneuvers trying to avoid a collision. However, Imo rammed Mont-Blanc in the starboard and several barrels of benzole were broken as a result.

The captain of the Imo reversed, but when disengaging the vessels, there was friction between the metal of the two boats. This friction caused a shower of sparks which ignited the benzole.

The captain of the Mont Blanc immediately commanded his crew to abandon the ship. All of them safely reached the shore, leaving the deadly cargo behind. After some time, the burning Mont Blanc approached the shore and came to rest against the wooden pier.

Many people in Halifax went to the embankment to get a closer look at the fire. Almost no one knew that there was a large amount of explosives in the burning ship.

At 9:06 AM, there was a huge explosion. The strength of it was indirectly confirmed when a 100-kilogram part of the Mont Blanc frame was found in a forest 12 miles from the epicenter of the explosion.

The destruction was catastrophic. The Richmond District, located in the northern part of the city, was almost completely wiped out.

Many people were burned alive or seriously injured. Others died of cold in the wreckage when a snowstorm began the next day. Fires that raged for several days covered part of the city.

According to official data, 1,963 people died (as of 2002, 1950 people had been identified) and about 2,000 were recorded as missing. After the explosion, another 1,600 people died. Out of three urban schools with 500 pupils, only 11 survived.

The last body to be recovered was found in the summer of 1919.

About 1,630 buildings were destroyed and 12,000 buildings were seriously damaged. The total damage was valued at approximately 35 million Canadian dollars. The Halifax Explosion was one of the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions.

The miniseries Shattered City: The Halifax Explosion (2003) is a fictional version of the event.

Mines in the Battle of Messines (1917)

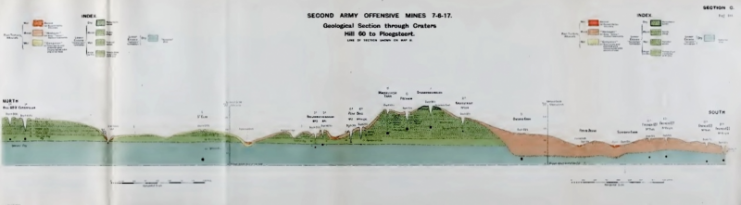

From June 7, 1917 to June 14, 1917, a battle took place between British and German troops, not farfrom the village of Mesen (known as “Messines” in French and English) in Belgian. Fortified German positions were located on the hills. The British command had long planned to destroy this bulge, but the offensive was threatened with heavy losses.

Given the experiences of Verdun and the Somme, the British developed a complex plan that required lengthy preparation and great effort. In developing this plan, the command took heed of the military truth: in war, the more sweat, the less blood.

For about 15 months, 20,000 soldiers dug 20 tunnels reaching a total length of about 7.5 kilometers (4.6 miles) toward the German trenches. The largest tunnel was about 650 meters (710 yards) long. The depth of the tunnels ranged from 25 to 50 meters (27 to 54 yards).

At the end of each of the tunnels, 25 explosive chambers were equipped with a total of 542 tons of explosives.

General Sir Charles Harington remarked to the press, “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography.”

To comply with the secrecy, all the work was done manually without using any mechanisms. At the final stage, the sappers worked without shoes so as not to attract attention through the noise of shoes on wooden flooring.

All the soil was poured into sacks that were lifted to the surface every night and taken to the rear lines. The entrances to the tunnels were disguised as domestic buildings and were located at a distance of 200-250 meters (218-273 yards) from the British trenches.

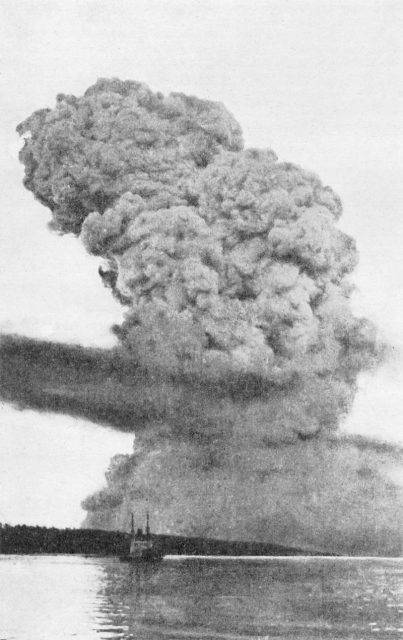

On June 7, 1917, the apotheosis of long efforts came and the bombs were detonated. Six charges did not work, but the rest was enough to destroy the German fortifications, as well as to kill and demoralize many soldiers.

As a result, the British managed quickly and with minimal losses to capture the Messinian ranks, to advance three kilometers (1.8 miles), and capture 7,325 German soldiers. During the explosions, about 10,000 German soldiers were killed or went missing.

Read another story from us: The Mines At Messines: The Biggest Explosions of the Pre-Nuclear Era

It is interesting that in 1955 one of the multi-ton charges that did not work during the operation detonated from a lightning strike. There were no human casualties, but one cow was killed.

The use of explosives in war has a long history, but in Messines the British set a record of scale.