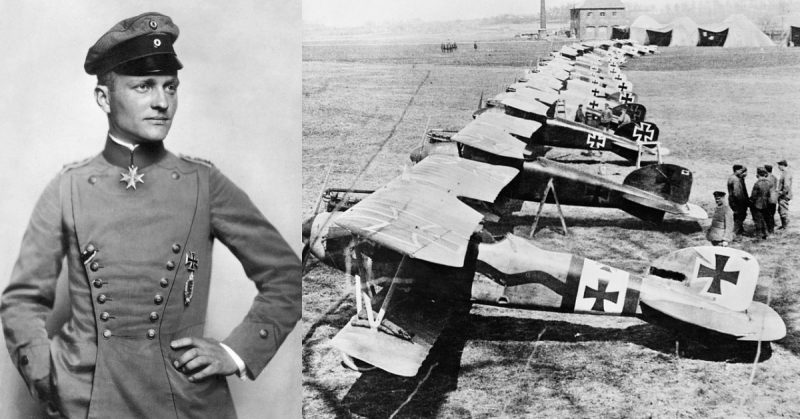

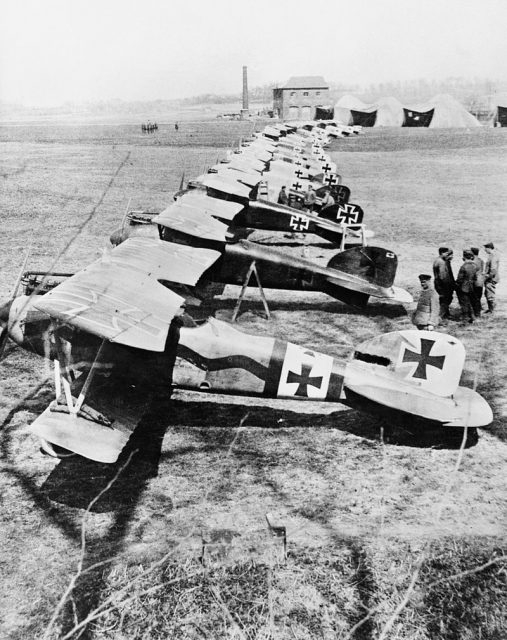

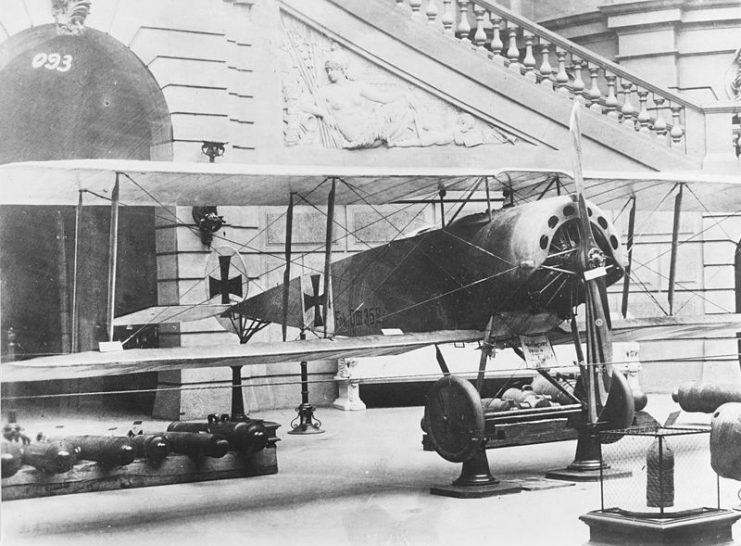

Though more than 100 years have passed and his record of aerial success was surpassed in WWII, to this day the flying ace that virtually everyone knows of is Manfred von Richthofen, “The Red Baron.” His red Fokker Dr.1 triplane is lodged in our collective memories. Actually, the plane is perhaps more widely known than his kill tally of eighty.

At air shows throughout the Western world, replicas of his famous red Dr.1 can be seen tooling through the sky, turning on a dime and chasing down the Sopwith Camels, Spads, and other Allied planes of the time.

“The Red Baron” flies regularly at Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome in Red Hook, New York. If the announcer suggested that the “Red Baron” had taken to the air, and the crowd didn’t see a red triplane, most would be confused and disappointed, but not those who really knew about “the Baron”.

You see, most of Manfred von Richthofen’s kills did not come while he was piloting the famous triplane. Actually, just the last seventeen of his eighty kills came while he was flying the Fokker Dr.1.

While he did shoot down two planes in the three-winged forerunner of the Dr.1, the Fokker F.1, the others he achieved in aircraft from two different aircraft producers: Albatros and Halberstadt.

Before we discuss the “other” planes flown by the Red Baron, here is a brief bio of WWI’s “Ace of Aces”.

He was born in 1892. Both his father and mother were Prussian aristocracy. Manfred, along with his two younger brothers–one of whom, Lothar, became an ace in his own right–spent his youth in the typical ways of the rich and privileged of the 19th century. He studied with private tutors, but spent most of his time hunting, riding, and doing gymnastics. He was supposed to have excelled at all three.

When WWI began, Manfred served in the cavalry, being an accomplished rider. He saw action on both the Western and Eastern Fronts, but when the war bogged down into the trench warfare synonymous with the conflict, he grew bored and was eager to transfer to the air service, which he had become interested in as a boy.

He transferred to the Imperial German Army Air Service, known as the “Luftstreitkräfte” (“air combat force”) in May 1915. He underwent two months of training as a gunner and observer, and then served a short period in the summer and fall of 1915 flying observation missions first over Russia, and then France.

At the time, the most famous German pilot was Oswald Boelcke, who wrote the “Dicta Boelcke,” a set of unofficial rules of aerial combat that still lays the groundwork for air to air combat today.

Richthofen met Boelcke, and this meeting convinced the young Baron to apply for fighter school. He also convinced his brother Lothar to join him. Lothar would end the war with 40 victories.

Manfred completed the course in one month and had a reputation as a below-average pilot. He crash-landed many planes initially and was lucky to have come out relatively unscathed. By comparison, his brother was considered the better pilot, and actually shot down more planes in a shorter time than Manfred, who was frequently out of action with wounds.

Still, Richthofen learned from his mistakes, took the “Dicta Boelcke” to heart, and used the skills he learned as a hunter to become the greatest ace of them all.

Manfred is reported to have shot down a plane while he was a gunner on observation duty, and also a French Nieuport in his first days flying fighters, but those reports could not be confirmed. His first seventeen kills, starting with his first officially confirmed kill, came while he was flying the Albatros D.II aircraft on September 17, 1916. This was equal to the number he shot down flying the Fokker Dr.1.

The Albatros D.II, as indicated by the name, was the second Albatros fighter. Obviously, the DII included changes and improvements, as both airplane design and flight science were growing by leaps and bounds through the necessity of war. Most of the improvements to the original D.I were made in response to pilots’ complaints about visibility.

The upper wing was moved forward and lower – the pilot could actually look over the wing at times when needing greater vision. The engines’ radiator was also low in the engine housing, which meant that when damaged, gravity helped it leak that much faster.

Eventually, the D.II had its radiator fitted into an airfoil-shaped housing on the top of the center wing. Still, if it was shot, scalding water could get in the pilot’s face. Later versions of the Albatros D series flown by Richthofen put the radiator in the front of the fuselage, canted to the right. This still made visibility tough, hence the lowered wing.

Other changes in the Albatros series included improvements in the strength and design of the wing struts, and improvements in engine efficiency and output, with a lightening of the weight of the plane relative to the output of the engine.

The D.II had a top speed of 110 mph, a ceiling of nearly 17,000 feet and a rate of climb of almost 600 ft per minute–contrast that with the most famous “climber” in modern history, the F-16, which climbs at 50,000 ft per minute. A pilot could fly for about one and a half hours on full tanks.

The armament consisted of a variety of 7.92 mm guns throughout its service life. The plane was powered by a 6-cylinder Mercedes engine, had a wingspan of just under 28 feet and was 23.3 feet in length.

The D.III had a top speed similar to the D.II but a greater rate of climb. The D.V increased speed to 116 mph. Each had a higher ceiling than its predecessor.

From kill number 18 to kill number 52, Richthofen flew a collection of various Albatros and Halberstadt planes. Each Albatros iteration made improvements on the last, and it was while flying an Albatros that Richthofen adopted the color red for his plane.

He was not alone in painting his aircraft in unique colors. Many German pilots adopted the custom – most famously those of the famous “Flying Circus,” or Jagdgeschwäder (“Fighter Wing”) 11. Richthofen eventually rose to command this famous and successful group of pilots, who wanted both friends and enemies to know who they were.

The Halberstadt D.II was similar in shape and design to the Albatros company’s planes. It had a thicker front section which tapered off radically towards the tail, though its streamlined appearance was marred visually by the radiator and top engine housing.

Many Allied planes, and later German planes, had their engines completely encased by the fuselage/cowling, to reduce damage and also mitigate the effect of the spray of oil and water from damaged engines.

The Halberstadt had been used early in the war, and Oswald Boelcke made his reputation in it. It had a top speed of only 93 mph, but was a solid plane. It also apparently turned well, as Boelcke pushed the plane to its limits in the search for advantage over his rivals.

Richthofen flew the plane near the end of its operational life – during WWI, advances in technology occurred almost weekly – and scored thirteen victories in it.

Read another story from us: Aviation Innovator – Fokker’s 4 Leading Warplanes

The Red Baron also briefly flew the Fokker F.1 triplane, which had been made famous by the ace Werner Voss. Voss’ famous last battle, in which he held off eight British planes alone for a long time before finally being shot down, was fought in the unbelievably swift-turning F.1.

Improvements in the wing design of the F.1 spawned the Dr.1, which Richthofen made his own.